Quite a portion of the debate on medical museum nowadays concerns human remains. Some museums suddenly have to deal with awkward origin of their specimens, while others now discuss the ethical side of their ‘babies in bottles’, which some visitors find hard to look at. Within this debate, the AMC Museum Vrolik, maintains a different strategy. While more and more human remains disappear from presentation, anatomic Museum Vrolik keeps them at front row.

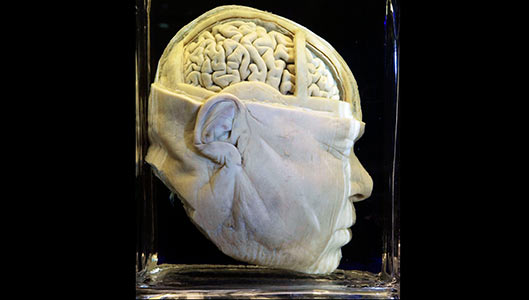

When you walk into this one-room museum, it is hard to remember you are actually in the middle of a grey, concrete hospital; an intentional contrast is created by a warmly lit, yet black room. It is clear that the exodus of human remains has not found resonance here: the room is filled with vitrines containing all kinds of body parts collected largely by Atonomy professor Gerard Vrolik (1775-1859) and his son Willem Vrolik (1801-1863). Helped by some older wooden vitrines against the walls, the museum feels like an classic, mysterious collection room.

Babies in Bottles

Laurens de Rooy, curator-director of Museum Vrolik, confirms this feeling to me. He tells me that, when he renovated the museum in 2012, he wanted to recreate a traditional anatomic museum; “One where one can wander between the objects”. Where other museum, such as medical Museum Boerhaave in Leiden, seek to modernise, Museum Vrolik seems to return to the past. The babies in bottles, physical abnormality and especially death, are an important part of this past, explains De Rooy. Historically, these are relevant because the themes were (and still are) a highly present part of life; biomedically, the containments of the bottles are still highly relevant. Hence, taking them out of museums completely, would be a loss.

©MuseumVrolik, Paul Bomers.

For Museum Boerhaave, the disappearance of their human remains was motivated by a goal to show the public that medical history is more than blood and gore. De Rooy seems not to worry about this alternative experience. “This [Blood and gore] is certainly not an angle we take at this collection, whether other visitors bring this view, is out of our hands”. De Rooy hopes to take some of the appalling feelings away through the aesthetics of the room. Admittedly, the presentation might stimulate biomedical interest as one wanders through the room and finds a particularly interesting object. Yet, the mysterious ambiance and simple beauty of the room might make the visitor forget that the museum has a historical dimension parallel to its medical angle. The aesthetics, although inspired by history, might actually overshadow the historical narrative that Museum Vrolik so elegantly tries to whisper in the ears of its visitors.

Objects and narratives

What stands out in Museum Vrolik is the little amount of text and an absence of digital media. The vitrines name the organ or physical deformity it contains and one can find some limited text on the walls, but other than that, visitors have to acquire the in-depth information themselves through booklets at the register or by booking a guide to tell you more about the collection. De Rooy tells me he often thinks “a strict and leading narrative in an exhibition can be a disadvantage for the object, which is no longer centrepiece”. Hence, Museum Vrolik tells no specific narrative through text, but rather tries to lure its visitors into sensing the biomedical and historic dimensions through the ambiance of the room and through the objects – at least if one is brave enough to take a close look. The objects will speak for themselves and De Rooy adds that he thinks that “[visitors] nowadays are sometimes spoiled with text and narrative”, which leaves little room for them to explore. Undeniably all these objects are telling, but without a tour guide, they will leave visitors with questions. This point was proven when a student approaches us to ask De Rooy if he knows at which age a person (who’s skeleton is on display) died, before he became part of the Vrolik collection.

©MuseumVrolik, Paul Bomers.

According De Rooy the object is (historically) central to the museum – something which is clearly reflected in the presentation. Digital media experiences would only direct the visitor’s attention away from the objects and they would trouble the experience of the museum. This approach is well chosen: it is the stillness of the museum that is charming (a paradoxical achievement, since the room is filled to the brim with objects). This would be lost if the small room would be crammed with digital screens. Nevertheless, one could repeat the previous remark here: if the museum tells a biomedical story on the one side, and a biographic story on the other, then why are the aesthetics the most important part of my visit? To De Rooy, the aesthetics are important because “the museum is the experience”, not the (digital) activities surrounding it. Yet, the experience of the museum, has not taught me much about Vrolik and the biomedical collection.

Looking at the future

Other than a slight overshadowing, the aesthetics play their part well. Museum Vrolik does seem to have found a way to put objects on display which are in controversy elsewhere. When I ask De Rooy if he would change anything now, he does admit that during the renovation in 2012 the fetuses where not hot topic yet. Now, he would like to remove a few, to balance the babies, which are only a small part of the collection, against the other human body parts.

A familiar museum battle between history and aesthetics seems to have been repeated here; my visit was highly commemorative, yet not necessarily because of historical enthusiasm or curiosity. However, to a visiting group of medical students, it did seem to be a small Walhalla and they might not encounter medical collections with this much care for the presentation very often. For a specific group of people with some background knowledge, Museum Vrolik is a great place to really explore; an activity which will definitely benefit their learning curve. To the ignorant visitor, Museum Vrolik is one of few opportunities to take a closer look at rare collection human remains within a beautiful, pleasant and mysterious environment.

Maartje van Bennekom

All quotes in this article were taken from an authorised interview with Laurens De Rooy at AMC Museum Vrolik on September 11, 2019.