In the past few years, Dutch farmers have been protesting against the new nitrogen laws. Through consistent appearances across both traditional and social media platforms, they have garnered significant public attention, resulting in widespread support from much of the public. But how could you get the attention and the support of the people without those uses? In this specific case, an American agricultural union used a lot of ingenious methods to get the public behind them.

“Viva La Causa!”

The story of this particular strike starts in 1962. Cesar Chavez, a son of Mexican immigrants, organized the founding convention of the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA). The NFWA was very unique, because it was the first permanent agricultural union in the United States. Under the motto “Viva la Causa” (Long Live the Cause), they wanted to improve the conditions of the mostly Latino farm laborers in the United States. Chaves himself started out in other social movements, but because of his background, he really cared about the working conditions of the farm laborers. He also was notoriously pacifistic, and even ordered the members of the NFWA to take a pledge of nonviolence.

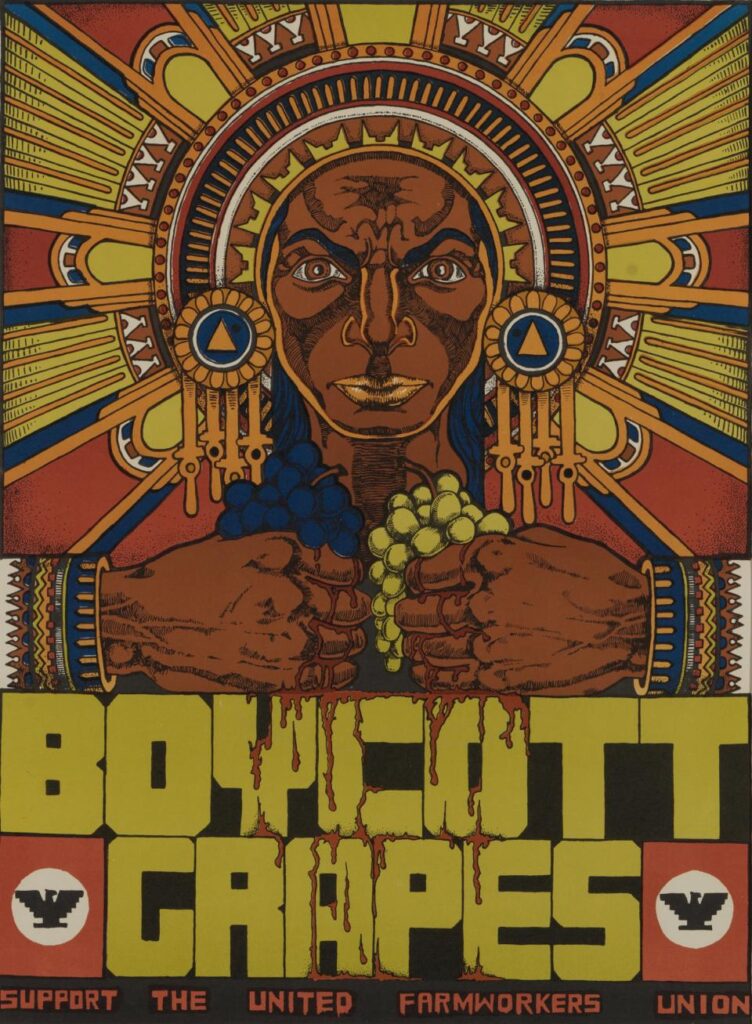

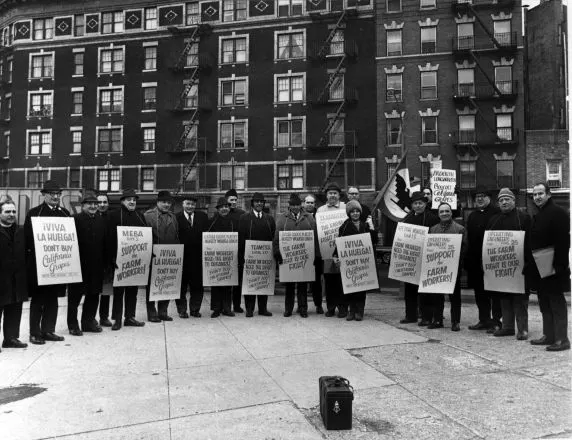

The major breakthrough of the NFWA came in 1965, when Filipino workers started a strike in the vineyards around Delano, California. They asked the Chaves and his union for help, which resulted in an alliance between the Filipino and Latino workforce on the farms. To seek awareness for his cause, Chavez organized a march from Delano to Sacramento, which caused so much attention that it lead to a deal with one of the major vineyard owners. After this victory, the strike lost the attention from the public, so they came up with a new plan: a grape boycott. People from the NFWA went out across North America to tell customers not to buy grapes. This worked very well and growers lost huge amounts of profit, which resulted in them making a deal with the union after five years of striking.

A recipe for a strike

Less then a month after striking a deal with the grape industry, Chaves and the NFWA turned their eyes towards the lettuce growers, who did not want to negotiate contracts with farm laborers. To keep the NFWA away from their industry, most growers negotiated favorable contracts with a rivaling union called the ‘teamsters’. In response, some 10.000 laborers started a strike in Salinas Valley, California on the 24th of august 1970. The so called ‘Salad Bowl Strike’ is still the biggest farm labor strike in American history.

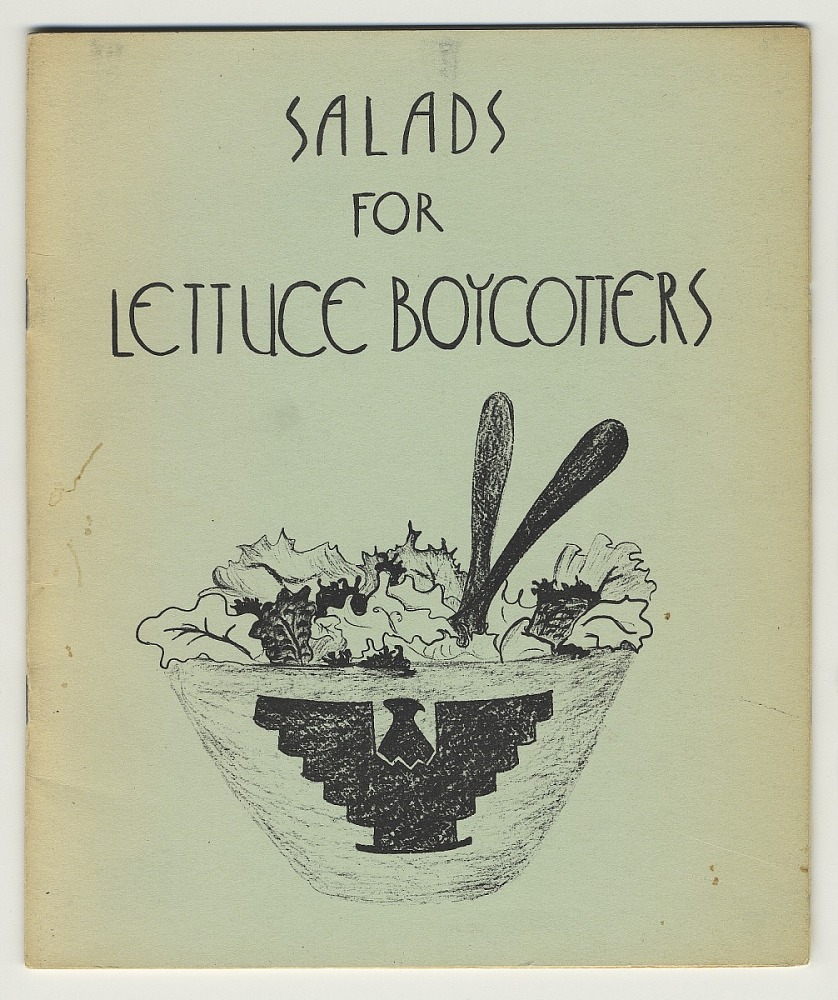

Public support would determine the success or failure of this strike. In September of 1970, the NFWA already asked customers all over America not to buy iceberg lettuce from non-unionized farmers, which had some success. But one the most ingenious ways the NFWA tried to make the public support the strike came with a pamphlet disguised as a cookbook called ‘salads for lettuce boycotters’. The price of iceberg lettuce skyrocketed because of the strikes, so many customers started looking for alternatives. In this booklet there were a lot of recipes for salads with iceberg alternatives, but it also contained the nutritional value of those alternatives, how you could easily grow or forage plants and even information about the wages the laborers got. In this way, they could not only help the customers, but also raise awareness about the strike, which helped them in the long run. A true win-win situation.

The effort paid off and the strike gained the support of the people, who helped sustain the boycott against the lettuce growers. Moreso, they also made a deal with the teamsters in march of 1971, which gave the NFWA the rights to organize the farm workers. For the next few years, the boycott and strikes continued, which provoked Chaves to seek out legal reform. In march of 1975, he organized a march from San Francisco to Modesto with thousands of workers to pressure the Californian government to pass a labor law reform. This resulted in the passing of the passage of the Californian Agricultural Labor Relations Act, which gave Californian farm workers more rights. They could now freely organize and negotiate union contracts with the growers.

From striking to a national holiday

Chaves’ work didn’t stop at the Salad Bowl Strike. When enforcement of the labor law ended in the 1980’s, the NFWA announced a new grape boycott. He also wanted to prohibit the use of harmful pesticides. To gain support for the public, he used another new tactic: fasting. In 1988, he fasted for 36 days to raise awareness, but didn’t really help the issue. He kept on working for the union until 1991. Two years later, he passed away at age 66 due to natural causes.

In the years following his death, Chaves has widely been remembered for his efforts. In 1994, Helen Chavez accepted the Presidential Medal of Freedom for her late husband from Bill Clinton. In 2012, President Barack Obama’s recognition of the Cesar Chavez memorial as a national monument increased interest in his legacy. His birthday, The 31st of march, is also a recognized holiday in 8 American states. It is mostly celebrated in California, where they try to honor his legacy by educating the people about his life and his goals. He showed America that fighting for your community is always worth it and that it could be done without using violence. As the man himself said:

“The fight is never about grapes or lettuce. It is always about people.”

Cesar Chavez, 1970

Written by Alexander Hilkens

Want to read more?

Desmarais, Annette Aurélie, Frontline Farmers. How the National Farmers Union Resists Agribusiness and Creates Our Food Future (Fernwood Publishing, 2019).

Levy, Jacques E. , Cesar Chavez: Autobiography of La Causa (University of Minnesota Press, 2007).

Rodríguez, Saryta, Food Justice: A Primer (Sanctuary Publishers, 2018).