A few years ago, a friend of mine moved to the Ferdinand Bolstraat, a lively street in the neighborhood ‘De Pijp’ in Amsterdam. I was having dinner with him when he started telling me a story about one of the most famous snack bars in the Netherlands, FEBO. “Did you know that the name FEBO comes from Ferdinand Bolstraat? They opened their first place on this street,” he told me. It’s a narrative that often circulates here in Amsterdam, and I had always taken it to be true, oblivious to the real story. As it turns out, the first FEBO made its debut on the Amstelveenseweg; it was only named after the Ferdinand Bolstraat because FEBO’s founder learned his trade there and had planned on opening his first business there.

Selling the ‘kroket’

Despite this mix-up in the origin story, the name FEBO is familiar to every Dutch person. The fast-food restaurant started small in Amsterdam but quickly expanded. In 2023 it has 74 snack bars spread all over the Netherlands, from which 27 are in Amsterdam. While you might associate FEBO with fried foods like the ‘kroket’ (croquette), what truly sets it apart is the iconic ‘snackmuur’ – the ‘snack wall’.

FEBO may be famous for its snacks today, but it began as a traditional bakery selling bread and pastries. Founded in 1941 by Johan de Borst, the bakery’s transformation into a snack bar began after he ate his first ‘kroket’ at Heck’s, an Amsterdam-based fast-food joint. Feeling inspired, Johan began creating his own fried snack recipes and selling them in his bakery. It was an immediate success, resulting in huge lines of customers.

The rise of the ‘automatiek’

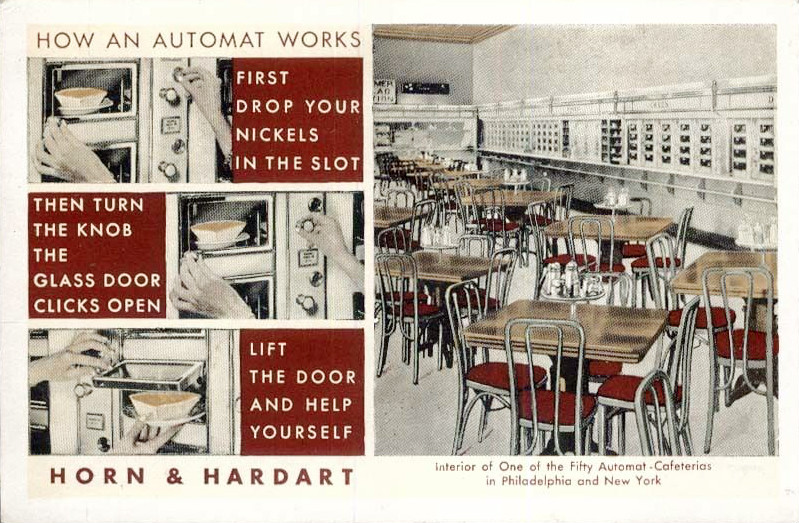

FEBO’s success was also partially due to shifting eating habits in the Netherlands during the 1960s. People wanted to eat quick and easy – to be able to get a snack on the go. In 1960, Johan de Borst opened his first ‘automatiek’ – a giant vending machine where customers inserted a coin (today, you can use your card or phone to pay) and selected their desired snack by pulling a handle. While FEBO’s automat wasn’t entirely unique, as the concept had its roots in Germany in 1896, it thrived in the Netherlands even as automats began to vanish elsewhere, for example in New York, which once held over 150 of them, mostly offering pastries. However, with the emergence of popular large fast-food chains, the automat slowly lost its importance in the United States.

Where automats lost their popularity in the US, they flourished in the Netherlands, particularly FEBO’s machines. In the ‘70s, the brand was rapidly expanding, with more snack bars featuring automats opening all over the country. The addition of milkshakes, ice creams, and French fries to the menu only increased their popularity. Furthermore, FEBO stood out by serving what they proudly call “daily and fresh products”, distinguishing them from other fast-food franchises that use frozen foods. Even today, FEBO’s snacks continue to be made from the traditional recipes of founder Johan de Borst, which have remained secret all these years. His grandson Dennis de Borst is in charge of FEBO nowadays, the business has always stayed in the family.

The snack bar as ‘low’ culture

Despite their massive success, there has also been criticism throughout the decades. In 1972, the Dutch newspaper Algemeen Dagblad published an article titled “Kritiek op de Kroket,” translated as “Criticism on the Croquette”. It acknowledged the snack’s popularity, stating that 182 million croquettes were being eaten annually, but raised concerns about health risks due to improper food preparation methods, particularly in automats. These machines, it argued, were breeding grounds for bacteria due to their internal heating systems. FEBO-founder Johan de Borst did not agree with the conclusions of the article and wrote a response to the newspaper, saying that “the croquette always had a difficult life” and that “the automats in the Netherlands are among the world’s best.”

There was not only criticism on the quality of the food; the snack bar as a place to eat was also seen as vulgar, distasteful, and lowbrow. When the automat with its snack foods was first introduced, it was seen as innovative and as food of the future, but during the ‘80s, this reputation shifted. “Where once the upper class used to shop […], now the youth walks with a FEBO croquette in hand […]” wrote the popular newspaper De Telegraaf about the Kalverstraat in 1983. Three years later, the Amsterdam-based newspaper Het Parool argues that the emergence of snack bars, including FEBO, in the Leidsestraat signaled neighborhood decay.

Over the past decade, FEBO has been actively seeking to gain new appreciation for their brand. Not only do they rely on their history and image as a family business, but they have also tried to embrace their nostalgic and simple appeal. This has led to the creation of merchandise and an unexpected collaboration with the famous rapper Donnie. Furthermore, they have also repeatedly recalled their association with the late Ajax football star and beloved Amsterdam icon Johan Cruijff, who was a lifelong customer of FEBO. By embracing their ‘low’ cultural status, their popularity rose again, drawing in a new, younger generation of fans and establishing their place in Amsterdam’s (food) culture. So, even though the myth about the first FEBO settling in the Ferdinand Bolstraat might not be completely true, FEBO will continue to hold a special place in the hearts and stories of the Dutch people.

Written by Marit Kroodsma

Hungry for more FEBO?

- Zuiderveld, Ubel. Febo: een Fenomeen. Amsterdam: Febo, Pop Food, 2011.

- Genootschap Amstelodamum, De Smaak van Amsterdam: 700 jaar stedelijke eetcultuur. Amsterdam: Virtumedia B.V., 2019.

- For the FEBO merchandise, check out https://www.febo.nl/shop/.

- For an example of FEBO’s collaboration with rapper Donnie, see below.