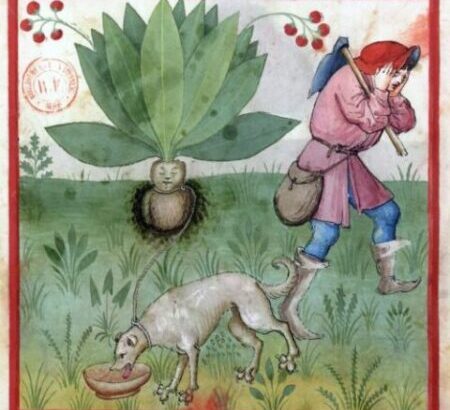

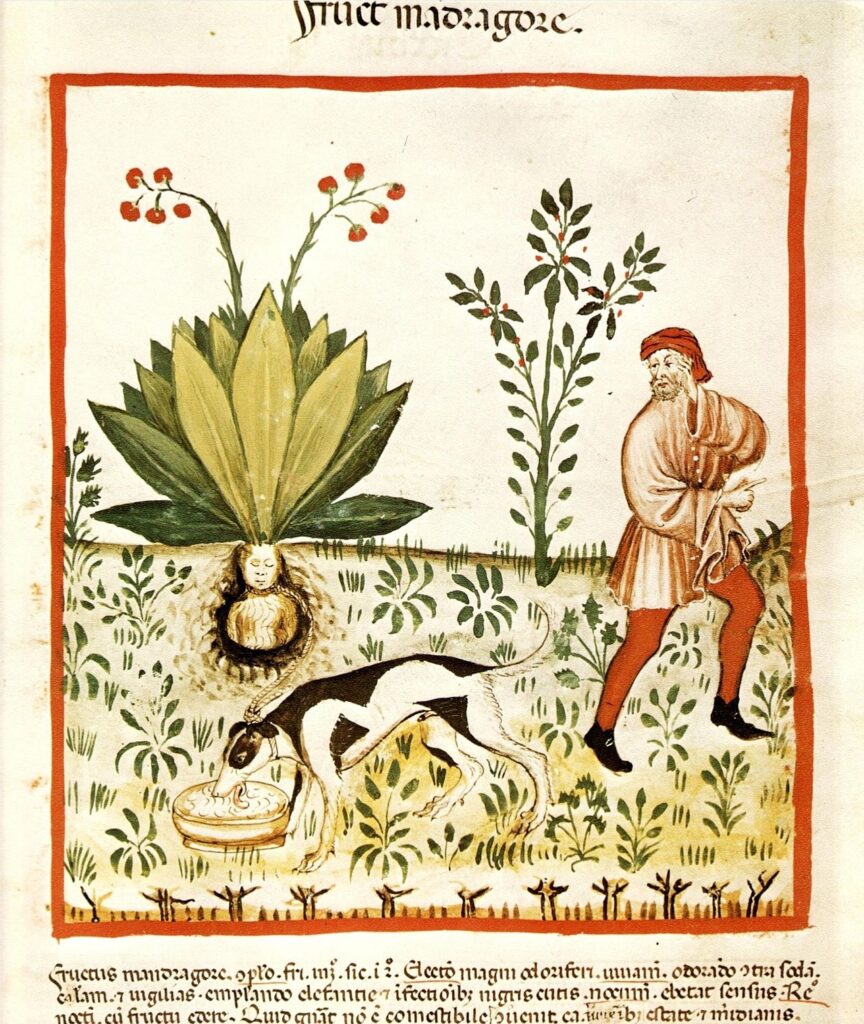

In order to pluck this plant, you need three things: a, preferably, sick dog, a bowl of food and a leash. Tie your dog to the plant with the leash. Give your dog one last hug. Walk as far away as possible, but not too far! Your dog still needs to hear you. Then place the bowl of food on the ground. Cover your ears with your hands. Summon your dog so he will run to you. And lastly, check if the dog is dead. If he is, then it worked! You’ve successfully plucked the plant! According to the myth, the cry of a mandrake when plucked is fatal. So how did it end up in a medicine book?

Tacuinum Sanitatis

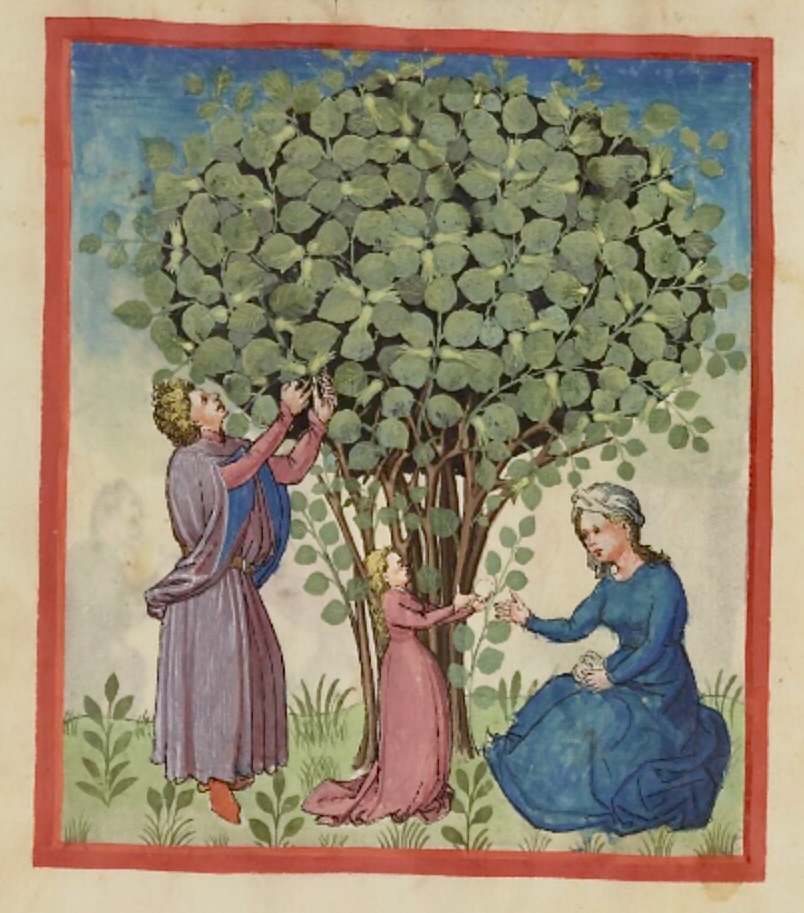

One of the most famous medicine books in the Middle Ages was the Taqwīm as‑Siḥḥa (‘Maintenance of Health’). Originally, this eleventh century handbook for health was written by Ibn Buṭlān in Baghdad. Two centuries later, it was translated to Latin and became known in the West as the Tacuinum Sanitatis. It was a big hit! Seventeen copies of the Latin version survived. The image below is from a fifteenth century copy made in the Rhineland.

Tacuinum Sanitatis, 2nd half 15th century, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Latin 9333 fol. 37r

This manuscript belonged to Count Louis of Württemberg and his wife, daughter of Louis of Bavaria, Count Palatine of Rhine and ended up in the Bibliothèque nationale de France. The text used to only be in Latin. In the sixteenth century however, a German translation was added beneath it. Could it have been done for the new German owners Count Louis and his wife? This, however, gives a good indication that these medicine books were not only used by physicians, but actually by all cultured lay people (the vernacular being the most common language in that time). Another indicator of it being a well-used book and an easy read is its name. The Italians adopted the Latinized word ‘tacuinum’ and changed it to ‘taccuino’, meaning notebook.

So, the common ‘all medieval people were dirty and unhealthy’ belief is actually far from the truth. Health was a huge deal in the lives of medieval people. The Tacuinum was not however a medicine book with potions or recipes on how to cure certain diseases. It was actually a preventative handbook on how to live a healthy life. The book consists of more than 280 objects and is split up into six sections: food and drink, air and atmosphere, motion and rest, sleep and wakefulness, secretions and excretions of humors and emotions or affections of the spirit. If one of these sections was off, your health was imbalanced. The Tacuinum traditionally begins with all the food items and herbs. Each page has an image of the object and underneath it the written explanations of the good and bad effects on your health. Sometimes, even the known myths or magical powers of the plants and under what circumstances you have to pluck them were described.

Benefits: good for intercourse and the brain

Harm: bad for the stomach

Sleep

Benefits: to restore the sense and the body and to digest food

Harm: if very long, it stimulates the body

Medicinal or Magical?

“Of all the medicinal herbs used in the ancient and medieval world, none was regarded with as much fear or wonder as the mandrake.”

Dafni et al., Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine (2021)

The Mandragora Officinarum, has a rich history of medical uses and magical powers. Due to the alkaloids, the plant causes hallucinations and even comas and was therefore a great narcotic. The Greek physician Dioscorides first used the root of the Mandrake as a surgical anesthetic in AD 60. There are also other positive benefits from medicinal mandrake such as relief of eye infections and rheumatic pains. However, being also extremely poisonous, accidental poisoning could lead to symptoms such as dizziness, diarrhea and vomiting. And also, yes, you could die. All of this should have been described in the Tacuinum Sanitatis. But that wasn’t the only book in which the plant was mentioned. The Mandrake has been a staple in every medieval medicine book.

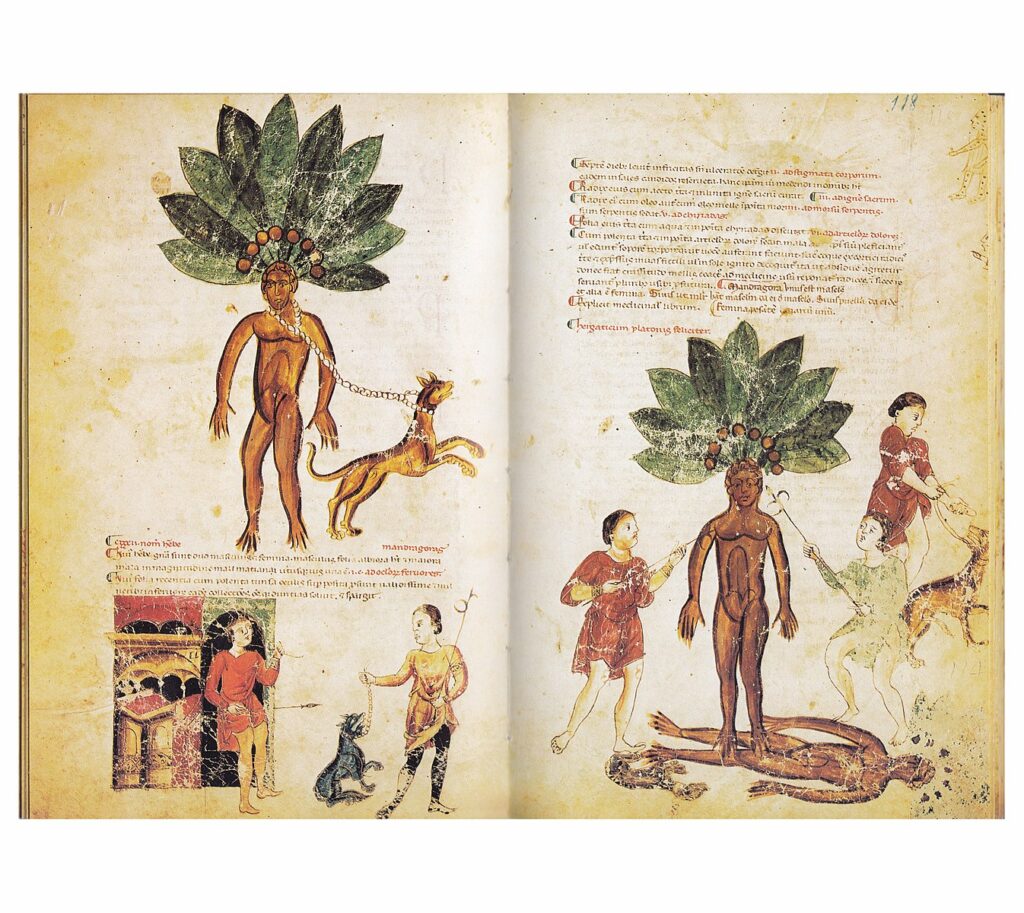

It was always depicted somewhat the same: a dog, a man and the human-like root-shape. And that last part, mixed with the poisonous and hallucinogenic character made the plant extremely well suited for myths and witchcraft. Because the roots have an uncanny resemblance to human limbs, the mandrake was thought to be a sort of demon with magical powers. Special incantations, prayers and dances were therefore necessary to be able to pluck them. And as demons were part of black magic, the mandrake quickly became associated with witches. Most famously, it was a key ingredient in the witches’ flying ointment. However, the magical powers of the plant were not all bad. The plant itself was often used as a talisman and good luck charm and treated with great tenderness. It was believed to bring wealth, power and protection amongst other things. The Church wasn’t happy with this pagan practice. Wearers of these charms were often accused of invoking demons and were sometimes even tried for witchcraft. Joan of Arc, suspected-witch who was burned at the stake in 1431, was also believed to be in the possession of a mandrake talisman.

Even the fictional witchcraft has mentioned the plant. In Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets Professor Sprout teaches the second-year herbology students its uses and how to repot them. Fortunately, they did not need to sacrifice a dog, fluffy earmuffs did the trick. Eventually the plants were used in a medicinal way: when fully grown they were the prime ingredient for a potion to cure those who have been petrified. And so J.K. Rowling cleverly nodded to the myth already present in the Tacuinum Sanitatis.

Nina Lammerts