In the Eerste Leliedwarsstraat in Amsterdam, you will find a very small museum dedicated to the influential Dutch writer Theo Thijssen (1879-1943). But the museum does not pay enough attention to its most precious possession: the exhibition space itself.

Theo Thijssen wrote several books that became part of the Dutch national canon, with ‘Kees de jongen’ (1923), ‘De gelukkige klas’ (1926) en ‘Het grijze kind’ (1927) as his most famous. The museum was founded in 1987 “to keep the memories of Theo Thijssen alive.”

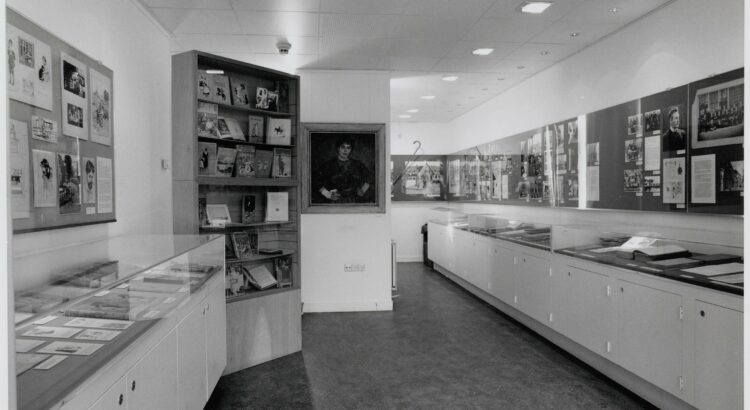

The museum operates mainly on donators and volunteers and welcomes about five visitors per day. Therefore, the museum is very primitive, consisting of a small permanent collection about Thijssen’s life, and varying exhibitions. It is all a bit primitive: basic information is printed on large pieces of paper and corrections are made on the glass frame instead of on the paper itself. But most surprisingly, the small museum does not mention its most important object: the exhibition room itself.

The 37-square meter room was the exact same room where Thijssen grew up as a child, together with his parents and five siblings. It has turned into a modern exhibition room with not a single authentic element. On the museum’s website there is little mention of the room and the way the family used to live, but no more than a few sentences.

One of the museum’s volunteers, Jan van der Maas, recently wrote a book about poor relief in Amsterdam from 1870 till 1940 and when asked about this room he had all the knowledge the museum itself was lacking.

“The Thijssen family did not live in an exceptional situation: it was very common during the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century to live with around seven family members on one floor.”

Jan van der Maas

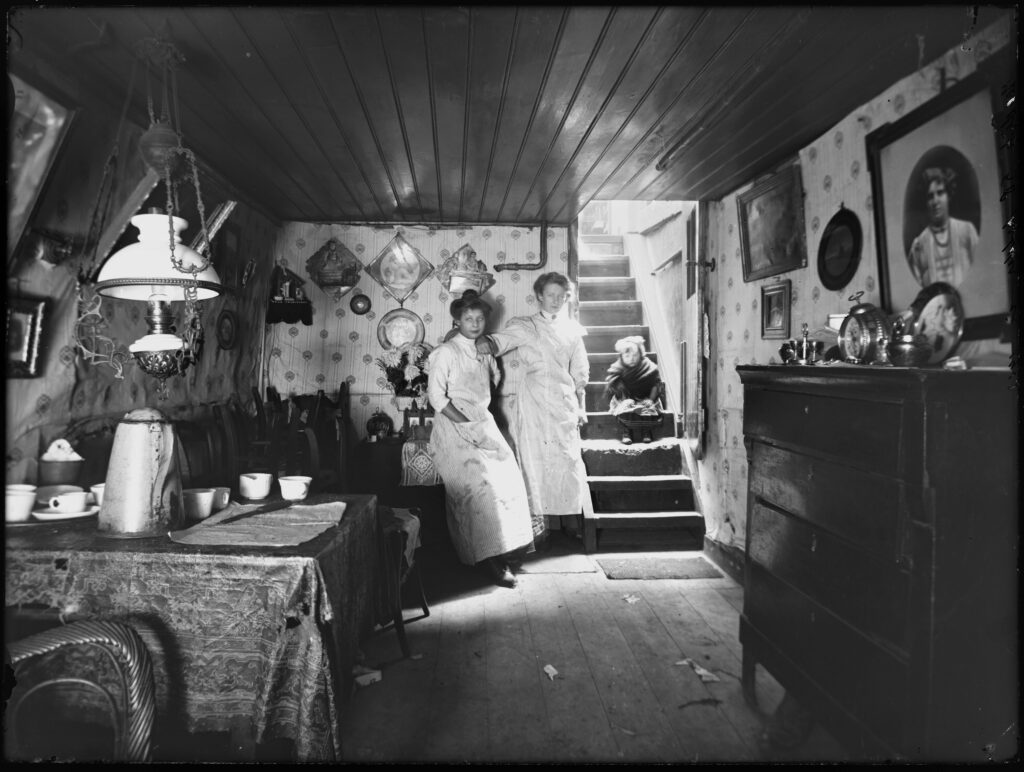

A curtain divided the living area from his father’s shoemaker shop in the front (which made the living area even smaller), as Van der Maas told me. The Thijssen family was a middle-class family and this former house was even relatively luxurious because “it had windows”. The lower class families lived in the so-called ‘basement houses’, without windows and with very poor hygiene. You can imagine what the lack of ventilation and sunlight will do to your mental and physical health.

The stories that Van der Maas told me, gave a lot more information about Thijssen’s life than the entire exhibition did. He also gave more insight into the connection between the housing situation and general health in the early twentieth century.

It is a pity that the Thijssen museum does not explore more interesting possibilities to use its exhibition space. As said before, the museum wants to keep the memory of Theo Thijssen alive, but only does so in the most basic ways possible: printed texts with some facts and photographs. Historian Hilda Kean emphasizes “the value of experience in the creation of historical meaning”, by which she means that there are more ways beyond the “conventional ways of exhibiting” to generate public knowledge and involvement.[1] Even though there are no traces left of Thijssen’s former house, once being aware that the room used to be home to eight people – including Theo Thijssen – gives a sense of the crowdedness and the living situations of that time. You can almost feel the claustrophobia. I would have loved to see an impression of the way the Thijssen family used to live. In order to feel this historical sensation, the museum could for example show a collection of historical objects, restore the house to its old state, or show photos of similar houses.

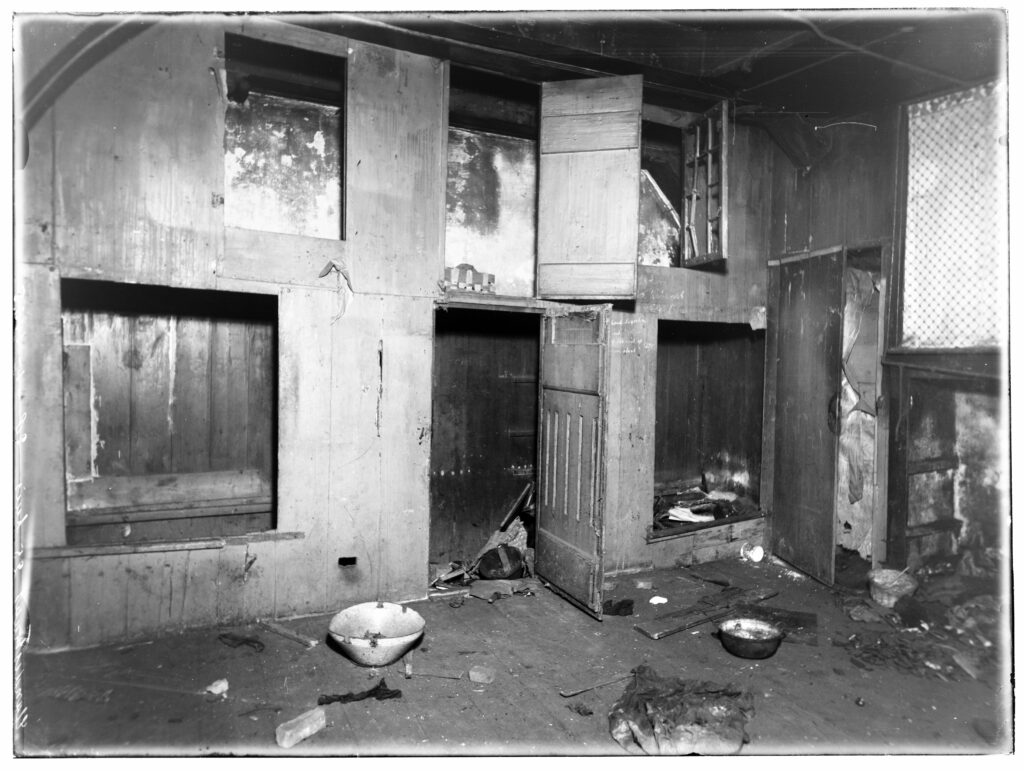

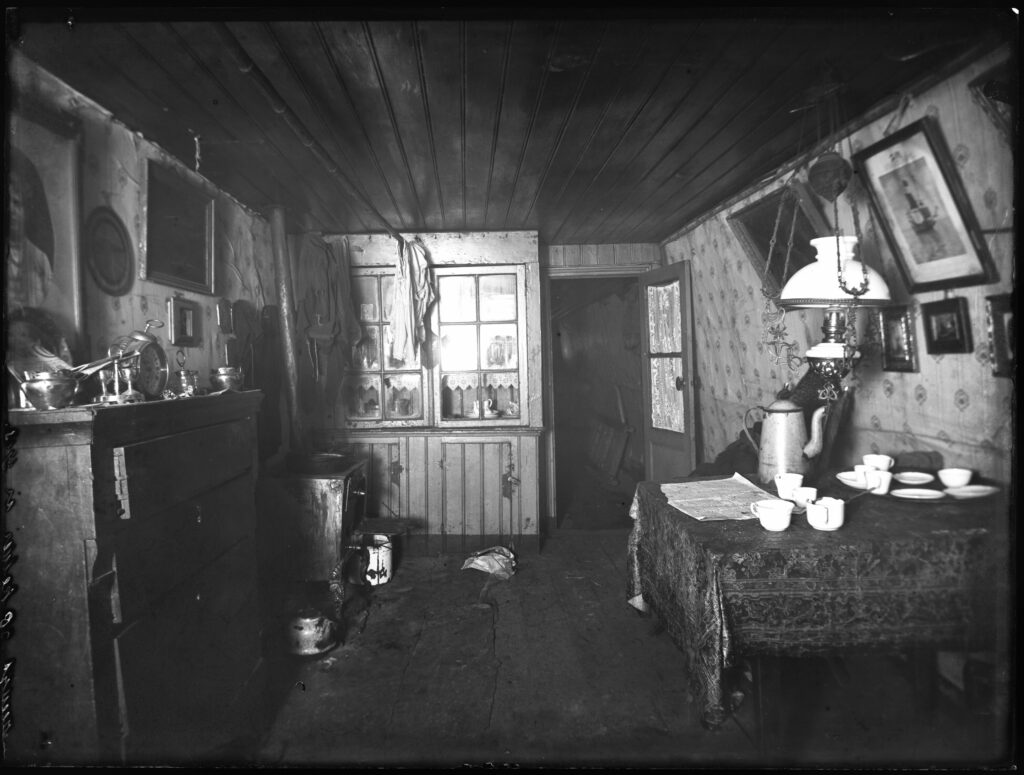

We learn from Thijssen’s highly autobiographical novel ‘Kees de jongen’ that his sick father was lying in a ‘box bed’. Photographs from the archive show how these box beds made effective use of space, like this house on Elandstraat 35 in 1935. The museum could have used a similar picture to is an example of information available to give an impression of the way Thijssen’s family used to live.

Historian Jennifer Tucker talks about the heart of public history as “ (…) developing a set of techniques or tools for thinking critically about society, historical change, and the different knowledges that make places meaningful both personally and as part of larger stories.”[2] By showing how people used to live and exploring the ways in which the housing situations had an impact on mental and physical health, the museum would have involved the larger story (a general sense of housing during the late 1900s and early 20th century) as well as the personal story. These days, there is an enormous shortage of affordable housing, which makes people either live with their parents, live in very small houses with shared facilities, or build up a huge dept because of the high rent prices. A recent study has shown that 60 percent of house seekers experience forms of stress and sadness as a consequence of the housing crisis. By emphasizing the connection between health and the general living situation, the museum would appeal to a large group in society.

The Theo Thijssen museum is special because it is located in the same house where the writer grew up. Sadly, they missed the opportunity to make the experience more immersive by giving people a true glimpse into the life of an early 20th-century household. It is also a pity that they did not seize the opportunity to connect their knowledge to current affairs. Plenty of room for thought for this museum to make better use of its beautiful exhibition room.

Lucie Galis

[1] H. Kean, ‘Public History as a Social Form of Knowledge’ in The Oxford Handbook of Public History, 405.

[2] D. Serling, ‘Guns, Germs, and Public History: A Conversation with Jennifer Tucker’, Journal of the History of Behavioral Sciences 57 (2021) 60-74, aldaar 62.