Listen to this soundtrack while reading this blogpost:

The object

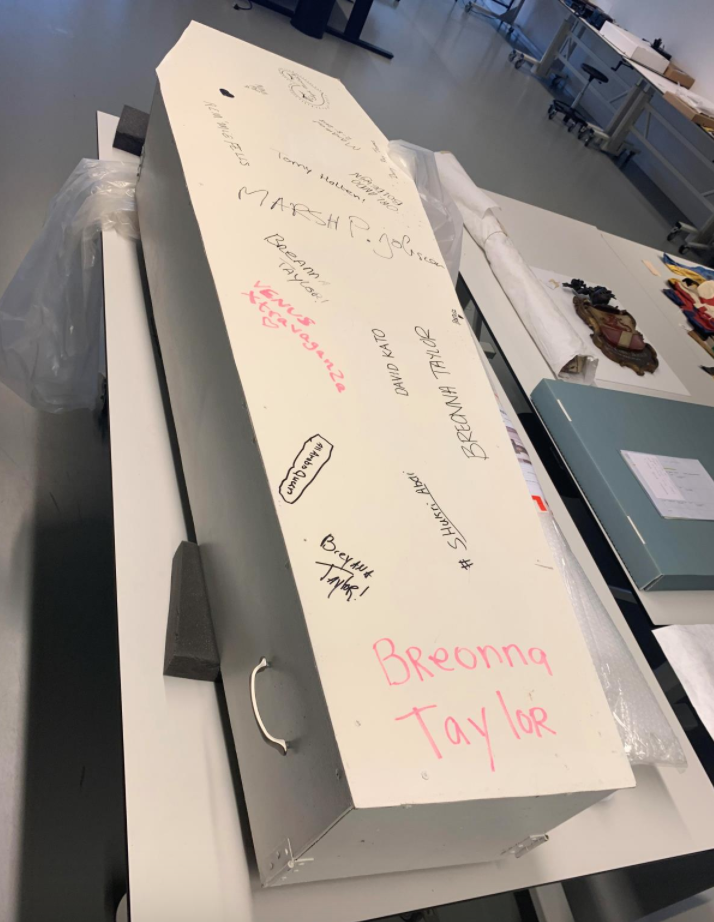

The ‘Doodskist Black Pride 2020’ is a white coffin for a human body, with silver carrier handles on the side. In total, there are four of these coffins. The names of victims of anti-black and anti-queer violence are written on the lid with markers.

The creators

The coffins were made by activist group Black Queer Trans Resistance NL (BQTRNL), which was founded in 2018, following the abuse of Xeverio, a Surinamese 24-year-old gay man. The founders of BQTRNL, Naomie Pieter and Wigbertson Julian Isenia, noticed that for white victims of anti-queer violence there is more public outcry, whereas for Xeverio there was close to none. To systematically address this they founded BQTRNL.

To make the intersectional struggle of black queerness an integral part of Amsterdam Pride, Pieter also founded Black Pride NL. The first protest took place on July 25th, 2020. Initially, the march would start at the National Slavery Monument at the Oosterpark, Amsterdam. This location holds significance for the protest as the performance ritual that the coffins were part of is based on Surinamese heritage practices. However, due to corona restrictions, the municipality only allowed a distanced demonstration at the Museumplein, which removed the locational significance of the protest.

The protest

Black Pride 2020 was well-attended for several reasons: The first heavy lockdown had recently ended, but no events were allowed yet. A protest –especially in good weather and serving as the opening event of Amsterdam Pride 2020– was a way to get out of the house and meet people. Besides, the brutal murder of George Floyd, which had taken place just a few weeks before, and the worldwide BLM protests that ensued afterward created momentum for this protest.

Use of the coffins

During Black Pride 2020, the coffins opened the protest: they were carried to the stage by people of colour, wearing white outfits. Near the stage sat members of an older generation of black feminist queer activists, such as Tieneke Sumter. Marian Markelo involved the coffins in a winti ritual, intending to honour those who came before us, both dead and alive, and to teach us that death is part of a circular pattern. It signifies endings as well as new beginnings, such as the beginning of Black Pride NL.

Use of coffins in activism historically

The use of these coffins during (black and queer) protests is not new. For example, in 1955, Emmett Till, a 14-year-old African American boy was abused and murdered by two white men after he allegedly whistled at a white cassiere while leaving a shop. Till’s action was unheard of in the highly segregated society of the Southern USA. Till was buried in a coffin with a glass case, as his mother demanded that the world see the injustice done to her son. After the two perpetrators were found innocent by the judge, they admitted to the murder: “just so everybody can know how me and my folks stand.” This unjust murder, the lack of repercussions and the pride that was taken in the act of murder are seen as catalysts in the civil rights movement.

“Just so everybody can know how me and my folks stand”

Milam, one of the murderers of Emmett Till, during an interview

In 2005, the case was re-investigated. To confirm with DNA cross checking that it was really Emmett Till’s body that was found, his body was dug back up. Afterwards, Till was buried in a new coffin. The old one was donated by the family to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Another era during which coffins and death symbolism were used during protests was in the 80s in the USA, during the AIDS pandemic. Marginalized groups including gay men, sex workers, and drug users were most affected by the spread of HIV and AIDS. With the main victims being a minority group, there was barely any political support to help them and so people began their own activist groups. One of these groups is ACT UP, which is known for its confrontational tactics and noisy protests.

Steve Michael, the founder of the ACT UP chapter in Washington DC, died himself of AIDS. It was his last wish that when he died, his body be taken to the White House. After he died, Michael’s casket was carried was part of a for once silent procession, to emphasize the voices lost during the epidemic. Michael’s death, and thousands of others with him, was literally laid at the doorstep of the political center: the White House.

Naomie Pieter and the Amsterdam Museum

Naomie Pieter’s influence on the ceremony at Black Pride 2020 is clear: educated as a choreographer, working as a performance artist and involved in many black emancipation groups she combined her expertise in different fields. Pieter made the protest into an artistic space for reflection, including taking care of material culture: creating a ceremony involving coffins made the protest much easier and desirable to archive. A smart tactic, especially for the marginalized voices represented here.

Archiving is a practice that Pieter is familiar with, as she also founded the Black Queer Archives in 2018. Why did she choose to archive these coffins with the Amsterdam Museum, instead of with her own institution? Several things need to be considered.

- Conservation: the Amsterdam Museum has the proper infrastructure to store these objects over time.

- Audience: the museum’s is bigger and more diverse.

- Money: the Amsterdam Museum paid BQTRNL for the coffins. This financial support can be used by the organization for future demonstrations.

For the Amsterdam Museum, the acquisition of this coffin seems to be part of their commitment to making black voices heard in their museum: in September 2019, they announced to no longer use the term ‘Golden Age’ to refer to Dutch society in the 17th century. Currently, they host the exhibition ‘The Golden Coach’, which is an investigation into contested heritage. On the side of the carriage are images of people from (former) Dutch colonies who are paying tribute to white people. To create a contemporary context, artists were commissioned to create artworks in which they reflect on this. One of the commissioned artists is Naomie Pieter.

Living heritage

That these coffins are part of a heritage that is actively being explored became clear even during the short span of time that I spent researching them. When I found the object online, no context was given. When I decided to use this item for my object biography, I reached out to Pieter and the Amsterdam Museum. While I did not receive a response, several days later a context description had been added to the online catalogue. And so, by researching this object, I have become part of the biography myself.

by Margot van der Sande