On Monday, 13 May of 1619, the Land’s Advocate of Holland Johan van Oldenbarnevelt (1547 – 1619) was beheaded. He was accused of treason by the States-General in, what is later called, a “show trial”. The Rijksmuseum houses a sword, which was said to be “the sword” with which Van Oldenbarnevelt was beheaded. The Rijksmuseum once stated that it became one of the most iconic objects of the History Department. But then another executioner’s sword turned up in the collection of the Staatlichen Kunstammlungen in Dresden, thanks to the research of the German historian Gisela Wilbertz. This brings up an interesting question about the credibility of musea and authentic objects: does it matter?

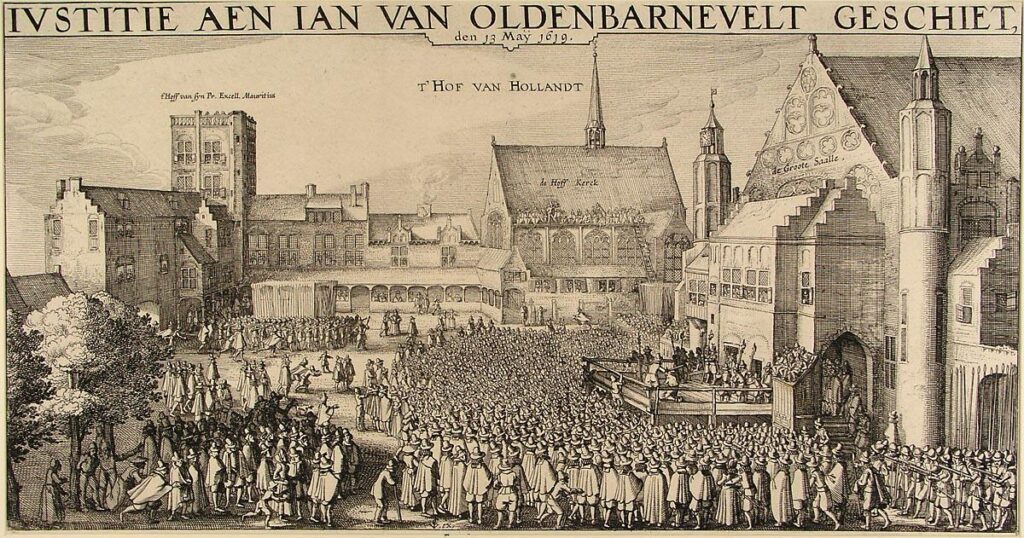

Oldenbarnevelt geschiet, 1619, Claes Jansz

Visscher (Rijksmuseum)

“Veltscheerder van Bernevelt“

It is said that the execution of Van Oldenbarnevelt was done with just one stroke of the sword. Normally, the execution was carried out by the executioner of the Hof van Holland. But the official executioner, mister Jacob Mosel, was ill at the time and could not do it. He was replaced by the executioner of the Court of Utrecht: Hans Pruijm, an experienced executioner from Zutphen. Hans Pruijm was a high-class professional and because of his qualities he was allowed to use his own sword. But, which sword is it?

Frans Greenwood (1680 – 1761) was a Dordrecht glass engraver. According to Greenwood, the left sword, the one he possessed, is certain to be the one with which Van Oldenbarnevelt was beheaded. While I certainly understand why the man would want the sword he possessed to be the sword, it turns out that it is very unlikely. Historians have researched the origin of the sword. Firstly, it is debatable whether the sword is an executioner sword at all. It has a pointed tip, whereas normal executioner swords have a flattened or rounded tip. Although it is unusual, there are exceptions where the executioner’s swords did have a pointed tip. Secondly, nothing is known about the early history of the sword and the “known” history has been partly passed on by word of mouth. In addition, Greenwood had patriotic ideals and pro-Republic sympathies. Although it is speculation, it is possible that it was convenient for him to see this sword as the real sword, because it functioned as a relic.

The right sword has more potential to be the real sword. The sword was in the armoury of the Staatliche Kunstkammer in Dresden. The German historian Gisela Wilbertz discovered that it was a sword belonging to Hans Pruijm, the executioner of Van Oldenbarnevelt. Although it is most likely a sword of Hans Pruijm, it is still not certain that he actually used this specific sword.

In the television programme Historisch Bewijs (Historical Evidence), three experts delve into into national historical objects. They investigate the authenticity of these objects, In other words: are they real? The three experts worked at the Rijksmuseum: Martine Gosselink, the former head of History, Robert van Langh, head of Conservation & Science and Stephanie Archangel, curator. In each episode, they examine a different relic from the Dutch history. In this programme, they have devoted one episode to these two executioner’s swords. Together with a team of researchers, they dive into the archives and do technological research. Their conclusion is the same as above. To watch the episode, click on the link (it’s in Dutch): Historisch Bewijs (Afl. 1 – Zwaard) Or you can watch an interview with the experts at the television programme OP1 (also in Dutch):

As you can see, these objects are still relevant, because it shows that even in museums, claims of authenticity do not always have to be true. Does that always affect the credibility of museums? Quite not. The Rijksmuseum sword is on display in room 2.5 in the Rijksmuseum: “17th Century: Power struggle in the young Republic”. The description right now says:

“While this is certainly an executioner’s sword, it is highly doubtful whether it was used to behead Johan van Oldenbarnevelt. The provenance of this murderous weapon goes back no further than the 18th century. It was in the possession of the poet Frans Greenwood around 1745. He probably had his own verse engraved on it, dedicated to ‘the innocent hero, poor wretched Oldenbarnevelt’.” (Rijksmuseum)

So the description now states the uncertainty of authenticity of the object. Nevertheless, the sword remains in the collection. Why? Taco Dibbits, director of the Rijksmuseum, says:

“Although it probably is not the real sword, the sword at the Rijksmuseum also tells a story. It came into our collection in the nineteenth century, a century in which they were searching for the identity of the Netherlands. We always want a tangible memory of our history and if that memory is not there, we make it.”

The authenticity of “one of the most iconic objects” of the History Department of the Rijksmuseum is not what people thought it would be. Yet it has been given a function that is linked to the real story: a tangible function. So although it is not the real sword, the Rijksmuseum hopes that the sword is still a tangible reminder of the real story of the decapitation of the old statesman: Johan van Oldenbarnevelt.

by Julia Morren