Since the COVID-19 outbreak, much more attention has been paid to hygiene, such as washing your hands regularly. Nowadays, we assume everyone knows that that will help against the spread of diseases. In Victorian England, this was not yet the case. The importance of clean water and personal hygiene was unknown for a long time and people thought diseases such as cholera spread through air, especially bad odors. When doctors and scientists found out that these diseases spread through dirty water, drastic changes in sanitation were made. This blogpost digs into a box of miniature sanitary appliances that helped teaching people about this.

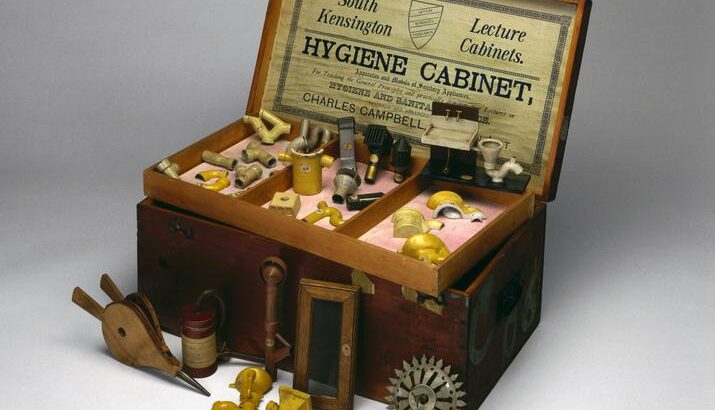

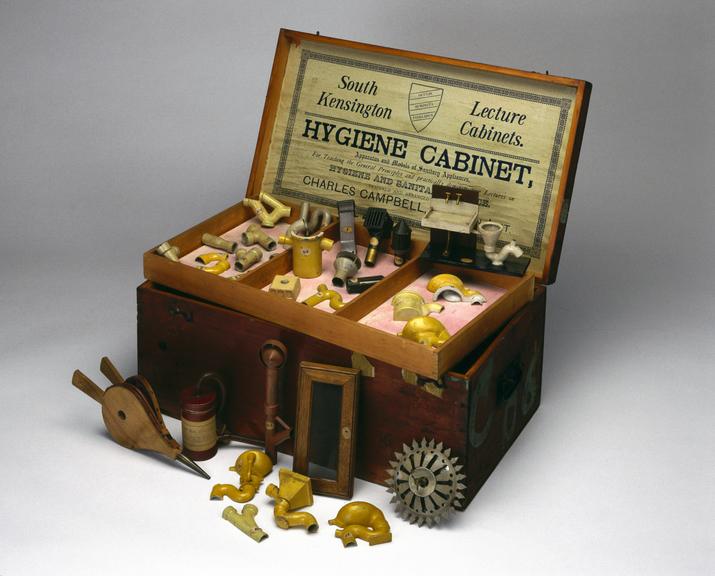

The collection of the Science Museum Group includes a wooden box with on the inside the inscription ‘South Kensington Lecture Cabinets – Hygiene Cabinet’, its function is also described: ‘apparatus and models of sanitary appliances. For teaching the general principles and practically demonstrating lectures in hygiene and sanitary science’. Below that, the name of Charles Campbell is inscribed, who designed and arranged this object in 1895. The wooden box contains three layers with all kinds of miniature models of sanitary appliances, sewage pipes, ventilation systems, etcetera. The models are made of earthwork and wood. Remarkably, some of the items are made ‘wrong’, with risk to hazards or not functioning properly.

© The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

This has all to do with the fact that, as the text on the inside of the box already gave away a bit, these models were used for lectures about hygiene and sanitation. Charles Campbell was member of the Sanitary Institute, founded in 1876. This institute gave, among other things, lectures to inspectors who did research in cities to find out in what condition the sanitary facilities were in, in the public sphere as well as in households. In order to do that, they had to know what safe, good sanitary looked like and what were possible hazards. These miniature models were an easy way of showing this and educating these inspectors.

South Kensington Hygiene cabinet. Detail view of pipes including sections. Science Museum Group Collection

© The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

South Kensington Hygiene cabinet. Detail image of sink. Science Museum Group Collection

© The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

South Kensington Hygiene cabinet. Detail image of Smoke Box. Science Museum Group Collection

© The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

This was necessary, because hygiene and good sanitary were not at all common yet in Victorian England (1837-1901). In this period, it was discovered that hygiene and clean water played an important role in the spread of diseases like cholera. At the same time, it was a period in which urban society emerged, especially in northern England where cities like Manchester, Leeds and Newcastle explosively grew in number of inhabitants, who lived very tightly packed on each other. This also meant a lot more pollution, people dumped waste in rivers where others got their water for washing for example. Nowadays, we can easily imagine how this caused a lot of health problems and why epidemics could spread so quickly. To improve these circumstances, new sewers and water supplies had to be installed and the inhabitants had to be taught what the importance of hygiene was and how to apply that in their daily lives. Hygiene and cleanliness became very important ‘Victorian values’, next to for example hard work and chastity. A popular saying in Victorian England went:

‘Cleanliness is next to godliness’

Unfortunately, little is known about how, why and when the Science Museum Group acquired this object for its collection. I can imagine how after a few decades, the general knowledge on hygiene improved and the use of for the miniature models decreased. Perhaps at some point they were not necessary anymore and gifted to the museum. About a couple of objects from the collection of the Science Museum Group, more is known when it comes to their transfer from daily life to the museum.

© The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

An example of this is a piece of pipe from Manchester, dating from 1890-1899, so about the same period as the box with models. This piece of pipe came in the museum after the renewal of pipelines in the centre of Manchester in the period 2007-2009. The pipe use to lay under Water Street, which is of course very suitable, and was taken out of the ground by United Utilities. It is not known whether this company or the city of Manchester decided to gift it to the museum or that the museum specifically asked for it.

© The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

In the collection of the Science Museum Group, many more interesting objects that relate to the 19th century project of getting better water supply into Manchester, such as a carbon water filter and a sluice gate, which was still in working order until 1971!

The goal of the box with sanitary models is in some ways still the same as it once was; to learn people something, albeit in a different context and a different story it tries to tell. In the 19th century, this object taught inspectors and indirectly the people in general about hygiene and sanitation. Nowadays, it teaches museum visitors (and online searchers like myself) something about the past, but also still something about sanitary facilities and their origin. The fact that the water sluice was still working until the 1970s and that the water pipes only got renewed in 2007-2009, shows how important this campaign was, then and now.

A last note I would like to make, because unfortunately there is not enough space to elaborate on this in this blogpost, is the role of women in the whole process of spreading knowledge about hygiene. When doing research on this object, I noticed how much attention was being paid to two women specifically when talking about this shift in how people thought about hygiene and living circumstances. First of all Florence Nightingale, a familiar name to many, who after experiences as a nurse in a hospital during the Crimean War did a lot for bringing better sanitary facilities and clean water supply into hospitals. Numerous exhibitions have been made about her life and work. Secondly, Hilda Martindale, one of the first female factory inspectors, who fought for better living and working circumstances. The Science Museum Group describes how she probably was taught about hygiene and sanitation through the box with models I discussed in this post!

Marijn Versteegen