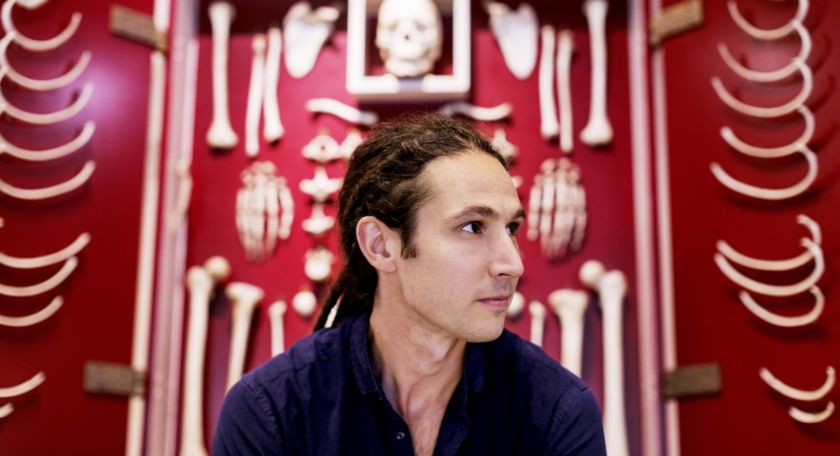

As Lucas Boer walks us through the Museum of Anatomy and Pathology in Nijmegen, sporadically stopping to tap on one of the many containers with human remains in them to get the air-bubbles out, he tells us about the way he designed the exhibition. It is obvious he spent a lot of time thinking about the issues that surround the topic. This is no surprise, considering he is presenting his dissertation about this collection and the future of Dutch teratological collections this very week. Teratology specifically is the study of abnormalities of physiological development; think about babies with severe dysmorphologies or rare birth defects. A big part of the exhibition consists of these kinds of specimens. And who better to ask about the ethical questions regarding this controversial topic than the only person in the Netherlands that actually studies these babies.

Article by Lina Smit

The Cabinet of Monsters

The word ‘teratological’ stems from the Greek words logos (‘the study of’) andtheras (‘monster’ or ‘marvel’). This double meaning is fitting for the way the researcher and public have historically reacted to the specimens in this collection. According to the Lucas’s dissertation the ‘monstrous births’ of the babies shock the observer, but the ‘wondrous creations’ nature can produce also fascinate. The challenge for any medical museum in the words of curator Lucas Boer is to intrigue observers without leaving them with negative emotions.[1]

The mission Lucas subscribes to the Museum is a very modern one: The way we look at these kinds of museums has changed a lot over the years. ‘Historically rationalized, these deceased children were seen as inert and impersonal entities. In today’s society they are increasingly depicted as personified entities,’ Lucas writes.[2]

He tells us that the collection of deformed babies was still called the ‘Cabinet of Monsters’ when he started here in 2012. One of his missions the past couple of years was getting rid of the ‘cabinet of curiosity’ that it was. Nowadays education and respect for the human body is an integral part of the museum. In positioning the foetuses he takes every remark into consideration. Furthermore, every object has a detailed description and there are 20 medical students that are responsible for guided tours and the provision of information.

Different museums, different questions

The focus of the museum on education is one of the main differences between the Anatomical museum in Nijmegen and other ones in the Netherlands, like Museum Vrolik, Museum Anatomicum and Museum Bleulandinum. These are all collections that consist of much older material and their curators are concerned with telling the history of their objects. Even though he acknowledges the importance of the history of the objects at display, Lucas is critical about the way these Museums handle their specimens. Specifically about Vrolik he says: ‘It is a historical collection: when you walk in there are 10.000 objects, you don’t know where to look.’ At Museum Bleulandinum as well as at the Bleuland Cabinet they also consciously make the decision to not display text signs next to the remains. Because they focus so much on the historical background of both their museum and their objects instead of on the educational value of the specimens it becomes a cabinet of curiosities. Meanwhile at Vrolik they emphasize that they specifically don’t want to create a freak show.‘ It is obvious that curators of these museums have not yet reached a consensus about the way the sensitive material should be handled.

At the heart of the discussion lie several issues. First of all, the question that is discussed above: Can one just show these – to some maybe shocking – human remains to the public? And if you do – How do you frame them correctly? Annelien Bredenoord, professor of Ethics in biomedical innovation at the UMC Utrecht, agrees with Lucas’s stance. She states that the display of the foetuses with congenital disorders is definitely something that can be justified for a museum that has an educational purpose. ‘You can at least inform the visitor at the entrance of the museum about why you made that decision.’[3]

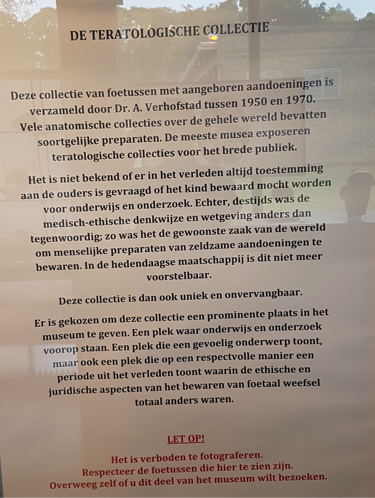

The issue is further complicated by the controversial origin of many of the objects: for some consent has never been given to display them. In the older museums this is even more problematic because of the colonial background of many of their objects. Only last year Museum Vrolik gave back human remains to a delegation of Maori. The Anatomical museum doesn’t struggle with the colonial aspect: All the foetuses have been collected in and around Nijmegen between the 50’s and 70’s. Nonetheless, a lot of their foetuses have also been obtained without explicit permission. Lucas reflects on the decision to keep them anyway: ‘It would be a shame to let them go to waste now.’ He emphasises the huge medical importance and unique nature of the specimens. Nowadays it wouldn’t be possible to obtain them because of ethical and legal reasons.

Reflections

The museum addresses these issues in several ways. There is a conversation with the public via a noticeboard with the goal to find out what the visitor perceives when confronted with the subject matter and to create a sort of ethical debate. Information about the dubious background of some of the foetuses and a warning about the nature of the exposition is provided in the form of signs all over the museum so people can marvel over natures wonders.

The conversation about the ethical implications of displaying human remains is thus ongoing. It is good to see that curators all over the country are sharing their visions both in the academic sphere, for example in the form of Lucas’s dissertation, and in the public sphere by talking about it to magazines, newspapers and audiences. It provides the audience of the teratological collections with the information they need to form an educated opinion in which they hold the past accountable as well as the present. In this aspect, the Teratological museum in Nijmegen succeeded with flying colours.

[1] Lucas Boer, The Past, Present and Future of Dutch Teratological Collections, From enigmatic specimens to paradigm breakers (Nijmegen 2019), 13.

[2] Lucas Boer, The past, Present and Future, 21.

[3] https://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2017/09/28/een-expositie-met-babys-als-museumstuk-13238162-a1575211

Featured Image of Conjoined Twins – Courtesy of Maino Remmers (NOS)