Twenty-one-year-old Private Victor Spencer was the last soldier during the First World War in the New Zealand army to be executed for desertion. His death was scarcely mentioned afterwards, as the fact was a great shame to his family and country. However, the silence changed after 2000 when the Pardon for Soldiers of the Great War Act was approved.

In April 1915, Victor Manson Spencer enlisted to fight in the First World War. The eighteen-year-old boy could not wait to serve in the army and lied about being twenty years old – the minimum age to serve in the military. After having completed his military training, he fought in Gallipoli. Earlier, he wrote that things were going well, “I have got a promotion to Lance Corporal, so I am no longer a private.” Nonetheless, he never received that promotion.

Next, the New Zealand Division was stationed at Armentières. In this place on the Western Front, Spencer suffered an enemy bombardment. He was evacuated, wounded, and found to be suffering from shell shock – something we would now diagnose as PTSD. When he was sent back to the trenches after a few weeks, he went missing almost immediately.

When he was arrested in mid-August, he was given an 18-month prison sentence with hard labour. After having served half of his sentence, he was sent back to his unit in June 1917. Spencer disappeared once more instantly. However, he was found again on 2 January 1918, living with a French woman and her two children.

Spencer was charged with desertion. He stated to the court-martial that he was not doing well:

“While in the trenches at Armentieres I was blown up by a Minnenwerfer and was in hospital for about a month suffering from shell-shock. Up to this time I had no crimes against me. Since then my health has not been good and my nerve has been completely destroyed. I attribute my present position to this fact and to drink.”

His superior officer, Captain McWatt, told the court in his statement that:

“The accused was a good soldier while he was with me. I had no fault with him. In NZ before we left the accused was recommended for one stripe.”

However, his superior’s co-declaration was to no avail. No medical evidence was required in court and the soldier was found guilty. Together with four other New Zealand soldiers, he was executed.

Justice will always be prevailed

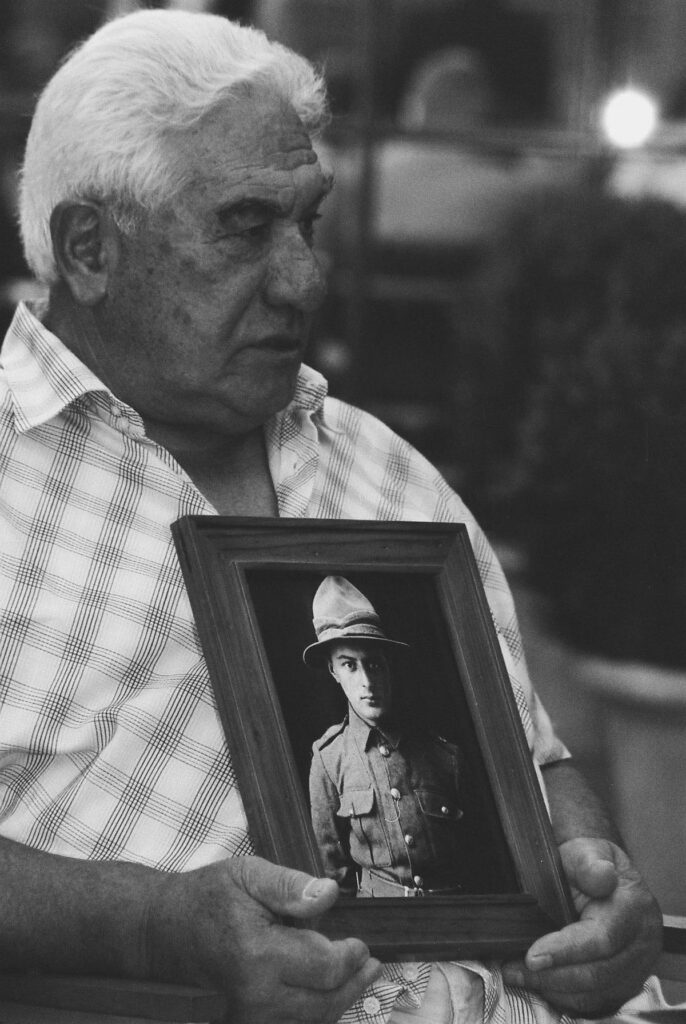

Decades later, Spencer’s second cousin, Spencer Morrison, wanted to serve the army. When Morrison told his father, the latter said: “Well, then I better tell you something about our family.” That was the very first time Spencer heard about his second cousin.

Victor Spencer’s story did not stop there. The book On the Fringe of Hell caught the interest of filmmaker Mark Winter. By researching the First World War, he subsequently came upon the executed, including Spencer. Unfortunately, neither documentary nor film ever materialised, but the information gathered about the soldier was shared by Mark with MP Mark Peck. It was this politician who, in 2000, pushed through the Pardon for Soldiers of the Great War Act. As a result, Spencer was, 82 years after his execution, officially pardoned for the crime of desertion.

On Australian and New Zealand Army Day (ANZAC day), Spencer’s family visited The Huts Cemetery in Dikkebus. They paid their last respects during a ritual that originated from the Maoris. For the sake of Spencer, and his family, being part Pakeha (New Zealander), part Maori. According to Maori custom, the official government statement was placed in a treasure chest (waka huia), together with a (hei) tiki.

A Maori tradition

Pardon voor Victor Spencer. Paper, printed. Ypres, In Flanders Fields Museum, IFF 002659.02. Images from the website.

Morrison hand-carved the waka huia for the grace of his second cousin Spencer. The treasure box is a custom of the Maoris. Waka means a narrow, long vessel, like a canoe for example. Huia refers to the tail feathers of the huia bird. Unfortunately, Spencer’s waka huai does not have these feathers, but this is not surprising as the bird is extinct.

The lid is decorated with a Maori mask sticking out a tongue and having haliotis-shell eyes. The function of the chests was to hold valuables. Traditionally, treasure chests like this one were hung from the house’s rafters, hence the cords. This way, the precious contents could be kept out of reach of others.

In the treasure chest is a green pendant, called a (hei) tiki. The part hei literally stands for charm and tiki for a human image. It is made of pounamu (a term Maori use for jade). The actual meaning or use of the hei tiki has been lost, though there are theories about it. One is that the tikis were buried when a guardian died in the Maori tribes. It was then dug up again later in times of mourning. The tiki was then passed on to the next generation to be worn. Therefore, the hei tiki connects the owner with his origin and ancestors, also called whānau (‘extended’ family). In this way, the mana, the importance of the hei tiki, continued to increase. In Maori terms, mana is what makes the world go round. Wars are fought over mana, but it can also stop wars; strength, prestige, authority, and power are terms that indicate this ‘umbrella term’. With this gesture, Victor’s whānau seems to give him an extra token of grace, which can also – of course – be found tangibly in the waka huia.

In Flanders Fields (Museum)

After the ceremony was held for Spencer, the family asked if the In Flanders Fields Museum in Ypres could take possession of the precious property. According to Piet Chielens, former museum coordinator, “this shows how a country and families can deal with a charged past.” According to Chielens, Belgium is not as good at this as, for example, New Zealand is in this case. However, this is precisely why this is the former museum coordinator’s favourite object from the collection they have in the museum.

The IFFM is an interactive museum that commemorates the First World War. The permanent exhibition shows the run-up, invasion of Belgium, the war in the country itself, and the post-war period. Emphasis is put on the stories of the soldiers who fought at the front. This way, stories are given actual names, faces, and voices. Just as Victor Spencer, who will never be forgotten thanks to his second cousin’s waka huai.

Written by Anna Noordeloos