In a time where ‘Black Lives Matter’-protests have revived and structural racism is being rightfully denounced, the relevance of the temporary exhibition ‘HERE. Black in Rembrandts time’ is undeniable. This exhibition by Elmer Kolfin and Stephanie Archangel in the Rembrandt house museum, focuses on the presentation of black people in the seventeenth century and wants to shift the attention to the people that are too often seen as secondary figures in paintings. Even though the exposition ended in the beginning of September, its relevance and unique approach make it still worth discussing in this blog.

The idea for this exhibition came from Stephanie Archangel, stumbling upon some of Rembrandts’ paintings in which she could finally recognize herself: “For years I’ve been looking for portraits of black people like me. Surely there had to be more than the stereotypical images of servants, enslaved people or caricatures? I found the alternative in Rembrandt’s time: a gallery of portraits of black people who are depicted with respect and dignity.” Teaming up with historian Elmer Kolfin, Archangel and Kolfin show with their exhibition that Afro-Amsterdammers have been there for a long time, and that they are all too often forgotten. More than just reintroducing the visitor to this lost history, the exhibition also explored the background of the people depicted. This was, however, not always an easy task. By showing the portrayed persons as individuals, they are not being displayed as a curiosity to look at but are presented as persons with their own story to tell.

Jacob van der Ulft, The Market in Dam Square, Amsterdam, 1653. Credit: Rembrandt House Museum.

By showing these portraits, the curators not only want to emphasize the presence of people of color in the Dutch society since long, they also challenge the current image that exists of black people in seventeenth century. ‘HERE. Black in Rembrandts time’ shows that the tropes about people of color haven’t always been there. Their depiction in the seventeenth century was rather realistic than negative. Getting rid of these negative stereotypes and caricaturist representation, this exhibition tells a more positive story, presenting an alternative image. The paintings – amongst which also Rembrandt – show that black people in the past are not automatically only secondary figures. They have been represented as self-aware and proud citizens. The curators tell a positive story, without losing sight of the negative side of this history.

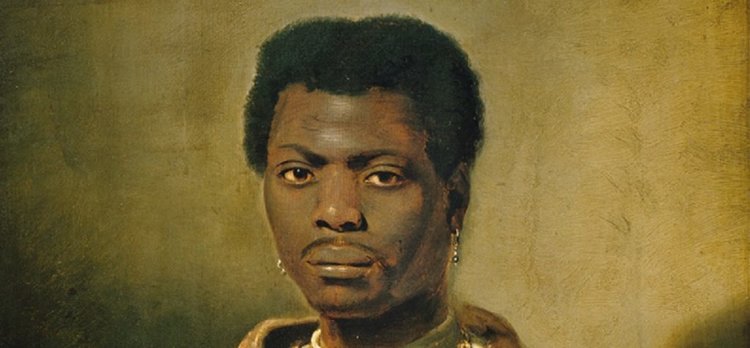

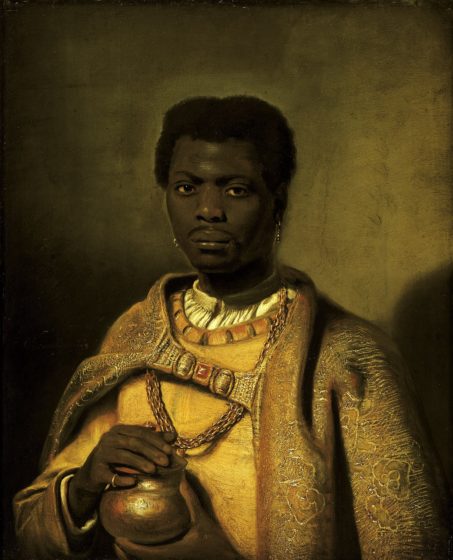

Hendrick Heerschop, Koning Caspar, 1654 or 1659. Credit: Berlijn, Staatliche Museen Preussischen Kulturbesitz, Gemäldegalerie.

‘HERE. Black in Rembrandts time’ is part of a bigger project called ‘musea bekennen kleur’ (‘museums admit color’). This project offers a platform for cooperation between museums with as goal more diversity and inclusion in museums, but also in society in general. The participation of the Rembrandt House Museum in ‘musea bekennen kleur’ shows that the exhibition ‘HERE. Black in Rembrandts time’ has a social ambition as well. The museum fulfills an active role in striving for a more inclusive society in which everybody has a place. The curators, thus, use the agency of the museum to convey this message and to stimulate change. Lidewij de Koekkoek, director states that “As a museum we hope that this exhibition will make an impact. ‘HERE. Black in Rembrandt’s Time’ is a powerful statement about black presence and representation in the Netherlands, about better looking and blind spots, about having a voice and a changing image.” To reach this goal, ‘musea bekennen kleur’ has a team of experts wherein a variety of disciplines and different backgrounds are represented. This team advises the participating museums, making sure that the representation is done in a correct and inclusive manner, without giving offence.

The voice of which Lidewij de Koekkoek speaks, is not only that of the black people from the seventeenth century, who remain partially unidentified. The exhibition also lets the present speak through the voices of ten contemporary artists. These artists reflect through their artwork on their own identity and on what it is to be a black person during these times. Offering a voice to both the portrayed, and the artists. These contemporary artworks offer also a counter-voice to art from the seventeenth century – and present – in which black people are reduced to secondary figures. This voice can be heard quite literally in the TED-talk of Titus Kaphar that was displayed is this exhibition. By contesting the way in which black people have been depicted, the exhibition attracts attention to this issue. The visitor is encouraged to look at Western art history in a different manner, focusing more on black people. The message that museum conveys, is one full of hope. Looking at the future, Elmer Kolfin and Stephanie Archangel see a positive change, which they hope to reinforce with their exhibition.

Jean-Paul Paula and Florian Joahn, Too Black, 2019. Credits: Jean-Paul Paula.

‘HERE. Black in Rembrandts time’ has rightfully so received a lot of positive media attention. The curators put black people in seventeenth century art in the spotlights, getting rid of the ideas that reduces them to secondary figures. In this manner, they question not only the past view, but also the present view on this topic. Yet, they are able to convey a positive message and express their hope for the future. This exhibition is not only about black people, but is created by and with black people of different background, adding to the strength of this exposition.

Written by Stien Wouters