In 1924 Thomas Mann published his novel The Magic Mountain: a masterpiece about medicine, death and disease. The story centers on the experiences of Hans Castorp, a young bourgeois German, at a tuberculosis sanatorium in the Swiss Alps. The book has had me in its tight grip ever since I bought it in 2015 and with a generous 900 pages, it’s the thickest book I didn’t finish yet. After two exciting tries I’m currently climbing it for the third time – and I’m still struggling. So, in an attempt to bring the book alive, I decided to visit Zonnestraal, Schip op de heide in Amsterdam-west; an exhibition that shows us the history of a world-famous Dutch sanatorium in Hilversum.[1]

Public enemy number one

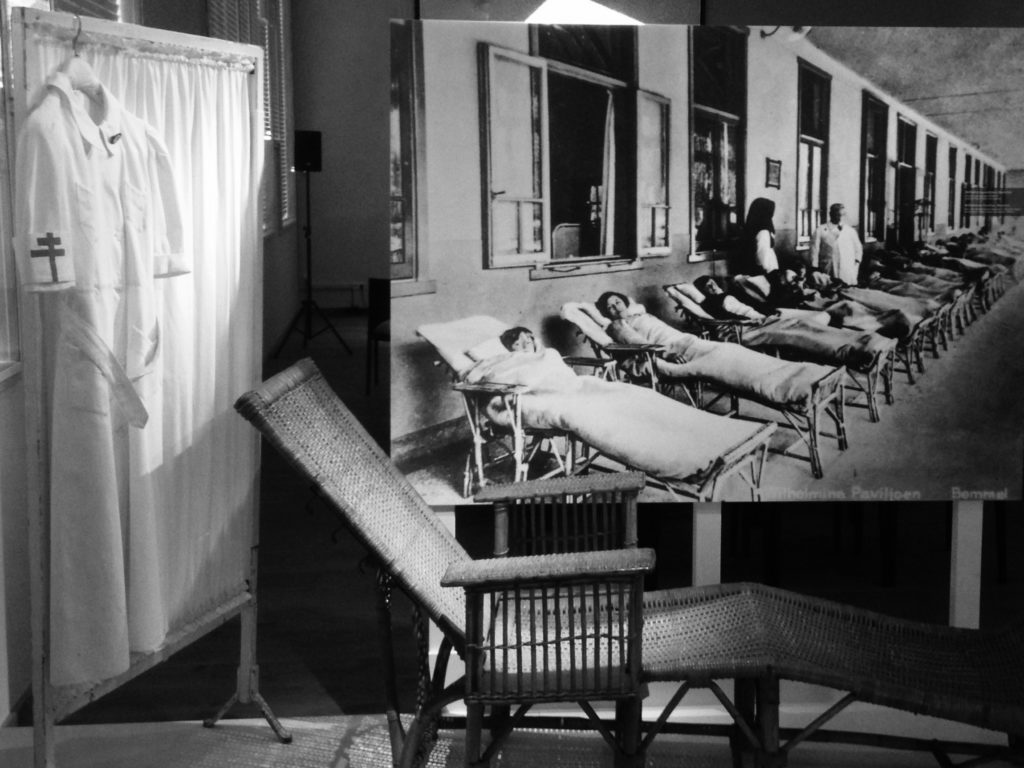

When you enter the exhibition in Museum Het Schip you’re immediately faced with the facts: tuberculosis was, and still is, one of the most lethal infectious diseases worldwide. At the dawn of the 19thcentury, the disease claimed ten-thousand victims each year in the Netherlands. TBC afflicted every section of the population, but mostly the lower social classes. While people from the elite were visiting sanatoriums to cure, poor working-class people were trapped in dirty cities. Terrible work- and living conditions were the most important allies of the tuberculosis bacillus: a lack of sunlight and ventilation, a lot of moist and poor hygiene were a lethal combination. The social consequences were enormous, especially when TBC affected the breadwinner of the family. Stigma made that people ended up in social isolation.

Hope for a better future

The most important information, like the above, is written on the hospital-white-walls of the museum, not to be missed. In the first room you can watch a short video, that tells you something about the architecture of former sanatorium Zonnestraal in Hilversum, which was created as a result of an unequalled belief in progress. It’s a typical example of modernist architecture, we find out; the white concrete, blue steel and transparent glass symbolizes hope for a better future. It reflects the concepts of air, light and hygiene in a highly functional building.

The realization of this unique piece of architecture starts in the dusty factories of the diamond industry. The diamond workers founded the first modern worker’s union in 1894 (Algemene Nederlandse Diamantwerkersbond) and they managed to improve the working conditions. Despite of that, the tuberculosis got worse. One of their members, Jan van Zutphen, then founded the Copper Stalk Fund (Koperen Stelen Fonds) and the union used the profits they made from copper stalks and diamond powder to buy the estate “Pampahoeve”; here they could build a sanatorium to cure people.

For a moment it feels like we are actually at Zonnestraal, as we look at big pictures of the monument in all it’s glory. Curator Joppe Schaaper (30) joins me and we walk through the exhibition together. For years the municipality of Hilversum has been trying to draw national and international attention to the sanatorium. Schaaper: ‘the adventure started for me when the municipality asked me to do research on Zonnestraal, because they were working on a request for the UNESCO world heritage list.’ Unfortunately, the nomination failed and the city of Hilversum had to find other ways to put the sanatorium in the spotlight; they turned to Museum Het Schip.

Social context

In the second room I listen to an audio clip of the Dutch Queen Mother Emma, who called for support for the tuberculosis control. A bust of Jan van Zutphen is shining in the center of the white space. Museum Het Schip is located in an iconic, ‘Amsterdamse School’-style building, designed in 1919 by Michel de Klerk. It was a safe haven for working class people who, after the implementation of the Housing Act (1902), finally found a good home.

‘The link with Zonnestraal is quite obvious,’ says Schaaper. ‘Architecturally spoken, the two buildings have nothing in common, but there is an important connection in social context. Over here it’s about work and over there it’s about health; the main incentive for both is idealism. People were living in bad houses and they suffered from terrible working conditions. A solution had to be found for that, so the people joined forces, everything based on a social enthusiasm; a belief in progress. That’s the kind of feeling I hope the people leave with, after a visit here.’

The people: quite an important factor in a social-historic museum like this, I would argue. The curator tells me that he has his own ideas about what the exhibition should look like. He didn’t want it to be ‘flat’ (solved by placing objects on different heights) and by using objects (like a cigar in an ashtray) that evoke a feeling of nostalgia he tries to make a personal connection with the visitors, he tells me.

Although I like the thought of the feelings he tries to evoke, I’m hoping that there might be some cooperation with the visitors, which, turns out, is not the case. Luckily, this has more to do with the fact that Het Schip is a small museum and Joppe had to collect his artefacts here and there, than with Huizinga’s wish to protect our stoic historical science from passionate and sentimental ‘plebeian people’.[2]‘I think the exhibition is clear and the people seem to be impressed,’ says Schaaper.

It starts with you

Idealism: I do feel it when me and Joppe walk past a big banner with the line ‘de sterken voor de zwakken’ (the strong for the weak). He shows me the third room, where there is some more information about the architecture of Zonnestraal and then we walk out. I ask him whether he has read The Magic Mountain…I will leave no further comment on his – slightly disappointing – answer. But I forgive him, because the exhibition gave me motivation. It gave me motivation in the first place to clean my room – and I hear you laugh – but clean rooms, clean streets, clean cities and clean countries in a healthy global environment is something to fight for. It starts with your own room.

Tuberculosis can be cured for over fifty years now. That is, in the so-called ‘West’. A quarter of the world’s population is still infected with tuberculosis, which means that on a yearly basis ten million people get infected, causing 1,5 million people their death. According to the RIVM (National Insitute for Public Health and Environment) it is the most lethal infectious disease. Apart from all the collecting boxes in the museum displays – crowdfunding for tuberculosis has been going on for a long time – Joppe also put up a QR-code; so visit the museum, get your phone out and donate!

And after you have done that; read The Magic Mountain or watch the film.

‘Schip op de heide’ is to be seen until 12 januari 2020 in Museum Het Schip, Oostzaanstraat 45 in Amsterdam. For more information about exhibitions and excursions to Zonnestraal, visit the website.

Paul Stam

[1]Bjørnar Olsen argues for objects as actors in the ‘drama’ of the narrative. I figured it might help me with my book. See: Catherine Colebourne, ‘Collecting psychiatry’s past: collectors and their collections of psychiatric objects in western histories, in: Catherine Colebourne and Dolly Mckinnon (eds.), Exhibiting madness in museums: remembering psychiatry through collections and display (London and New York, 2011) 25-26.

[2]For more about Johan Huizinga’s slightly old-fashioned, but still beautifully expressed opinions, see: Johan Huizinga, ‘De taak der cultuurgeschiedenis’, in: Johan Huizinga, De taak der cultuurgeschiedenis (Groningen 1995) 95-107.