Did you know that the rice table is listed as Dutch national heritage on the UNESCO world heritage list? It was even introduced to Macron as a typical Dutch dish by former prime minister Mark Rutte as they enjoyed a rice table together. Broadly appreciated and consumed by the Dutch people the rice table has its roots in former colony the Dutch-Indies. However it is neither an Indonesian, nor a Dutch dish. It is a product of colonialism which brought Dutch and Indonesian culture together and were merged together into one separate culture, the Indische culture. Bi-cultural food traditions can be used to illustrate migration histories. And so, in this blogpost the rice table is a powerful symbol of cultural fusion, particularly for the integration of Indische people (people of mixed Dutch and Indonesian decent) into Dutch society.

A colonial invention

To understand its multi-faced history, we must first go back to colonial times. The rice table was understood to be an Indonesian dish, meaning the activity of eating a rice table in good company was an indigenous practice. This was not the case. The rice table consists of a variety of Indonesian dishes such as nasi (fried rice), smoor (slow cooked beef in sweet soysauce), gadogado (vegetables in peanut sauce) and satay ayam or babi (chicken or pork skewers), all served simultaneously and in abudance, which historically symbolized the power dynamics between colonizers and the colonized. Therefore, serving a rice table was a sophisticated way entertain guests whilst showing off the wealth and diversity of the colony. It was a colonial invention that projected the power hierarchy, with Indonesian servants such as the kokkie (the female cook) preparing and serving dishes to Dutch, European or Eurasian guests. This separation between preparing and enjoying the meal emphasized the social hierarchies of colonialism.

Restrictions on rice consumption

The colonial times came to an end in the 1940s as Indonesia’s independence was recognized by the Netherlands in 1949. With this newfound independence came a new government and anti-colonialist political agenda which endangered Dutch people, as well as Indische people in Indonesia. Hundreds of thousands of Dutch and Indische people fled to the Netherlands. Unfortunately, the Indische people were not offered the same warm welcome as their Dutch counterparts. They were concentrated into pensions where they faced discrimination and poor living conditions. The Dutch government restricted the expression of their Indische heritage and culture as it was considered counter-productive to their integration into Dutch society. The consumption of rice was restricted and controlled by social workers who were able to weaponize it, meaning social workers could prevent Indische people from gaining proper housing if they considered them not integrated enough because they still ate rice. This racially motivated attitude was reflected in the Dutch society’s reaction to the rice table and the use of spices which were seen as “their food”.

Indische empowerment

Despite these challenges, Indische culture, and particularly the rice table, experienced a revival in the following decades. We can thank this popularization on the one hand to Tjalie Robinson, an Indische journalist who catapulted Indische cultural emancipation. Being Indisch, enjoying Indische food and music was now something to be proud of. And so, many Indische people proudly got to cooking rice tables, not only for their Indische peers, but also for their Dutch neighbors. On the other hand, the concept of “Tempo Doeloe” helped tremendously as it was understood by both Indische- and Dutch people who formerly resided in the Dutch Indies. Tempo Doeloe translates to foregone times and suggests a romanticized nostalgia to the colonial times where, in this case, the rice table was thoroughly enjoyed.

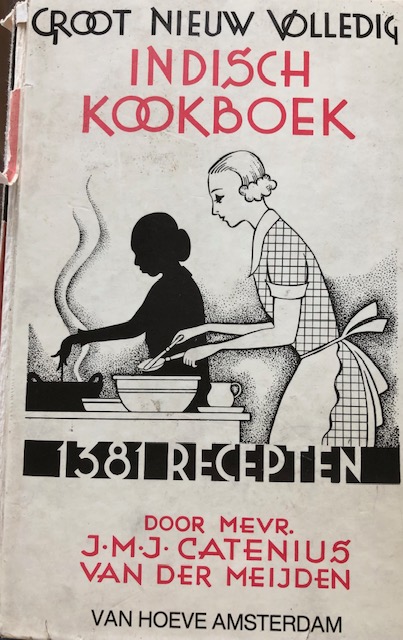

Toko’s, Pasar Malam and thousands of Indische cookbooks

This appreciation continued and the rice table lost its racial precedent. Over time, the rice table became an integral part of the Dutch society, embraced by both Indische people and the broader Dutch. Thousands of toko’s and Indo-Chinese restaurants have opened their doors, the Pasar Malam became a well-attended event and there are many Indische cookbooks. You could say that the rice table has integrated into Dutch society, the same as Indische people have. Indische people are often considered the best assimilated group of migrants in Dutch migration history. We could argue whether that is a compliment or an insult. Does integration into one culture mean having to let go of another culture? The popularity of the rice table proofs this statement wrong and shows how the integration of the Indische culture into the Dutch culture has been deliciously enriching.

Interested? Read more:

Lizzie van Leeuwen “Ons Indisch Erfgoed”

Matthijs Kuijpers “Makanlah Nasi! (Eat Rice!)”: Colonial Cuisine and Popular Imperialism in The Netherlands During the Twentieth Century”

written by: Veerle Bodeving