During a visit to my parents in the far north, we were trying to decide what to eat. No one felt like cooking, so we opted for Chinese takeout. My mother and I drove to the Chinese restaurant just a few streets away. When we arrived, we saw that we weren’t the only ones – many others apparently had the same idea, and as quickly as we arrived, our food was ready. It made me wonder how the ‘afhaalchinees’ (‘Chinese takeout’) has developed into a uniquely Dutch concept, with dishes that have been adapted to Dutch tastes over many years. The popularity of Chinese food in the Netherlands is even so widespread that the Chinese restaurant has become an integral part of the Dutch streetscape, and you can easily whip up a similar meal with a ready-made packet from any supermarket. But how did Chinese takeout become so wildly popular in our country? Let’s take a look at the history of Chinese restaurants in the Netherlands, the rise of Chinese takeout, and the Dutch adaptation of Chinese dishes.

The First Chinese Immigrants and the Rise of Chinese-Indonesian Restaurants

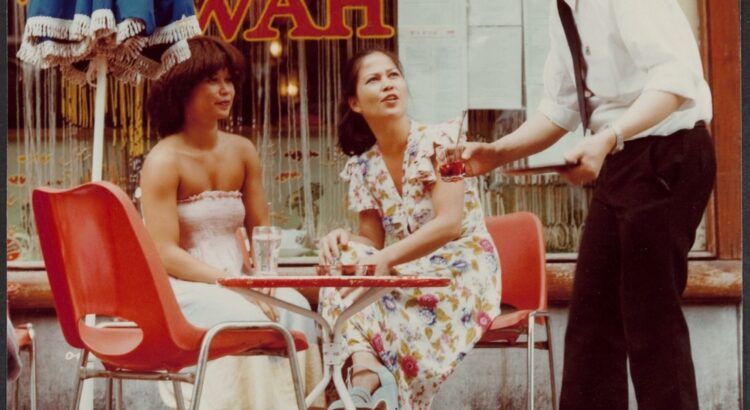

At the beginning of the 20th century, small groups of Chinese migrants settled in the Netherlands, mainly sailors who disembarked at the ports of Amsterdam and Rotterdam. To accommodate these Chinese immigrants, boarding houses were built, leading to the development of Chinese communities in these cities. Due to the economic crises of the 1920s, many Chinese dockworkers could no longer find work, prompting some to sell small trinkets or peanut cookies on the streets. Others opened eateries that primarily catered to the Chinese community, offering simple, home-style dishes that provided a sense of familiarity.

The first Chinese restaurant, Cheung Kok Low, opened in 1920 in Rotterdam, while Kong Hing, which opened in Amsterdam in 1928, became the first Chinese restaurant to attract Dutch customers. It became necessary to cater to a broader audience, as many Chinese immigrants had left the Netherlands due to the economic crises. Many of these restaurants were concentrated in Amsterdam’s De Zeedijk and Nieuwmarkt areas, and in the Katendrecht neighborhood in Rotterdam.

After World War II, the character of Chinese restaurants in the Netherlands changed significantly. Following Indonesia’s independence, many Indo-Dutch migrants and Dutch soldiers, as well as a group of Chinese-Indonesian migrants, settled in the Netherlands. These newcomers, accustomed to Indonesian cuisine, created a growing demand for Indonesian dishes. In response, Chinese restaurants expanded their menus to include popular Indonesian dishes such as saté, gado gado, and nasi rames. Cooks with an Indonesian background were hired to prepare these dishes and to teach the recipes to their Chinese counterparts. This fusion of Chinese and Indonesian culinary traditions gave rise to the unique Chinese-Indonesian food culture that became a staple in the Netherlands.

The ‘Dutchification’ of Chinese Food

The ‘Chinese-Indonesian’ food culture quickly gained popularity, with dishes being adapted to suit Dutch tastes. Portions grew larger and the dishes became less spicy, allowing both the Indonesian community and a broader Dutch audience to be catered to. This ‘Dutchification’ (‘Vernederlandsing’) of Chinese dishes resulted in the creation of beloved dishes such as babi pangang, foe yong hai, and tjap tjoy, all of which have been reinterpreted to meet Dutch preferences. Consequently, the popularity of these dishes soared.

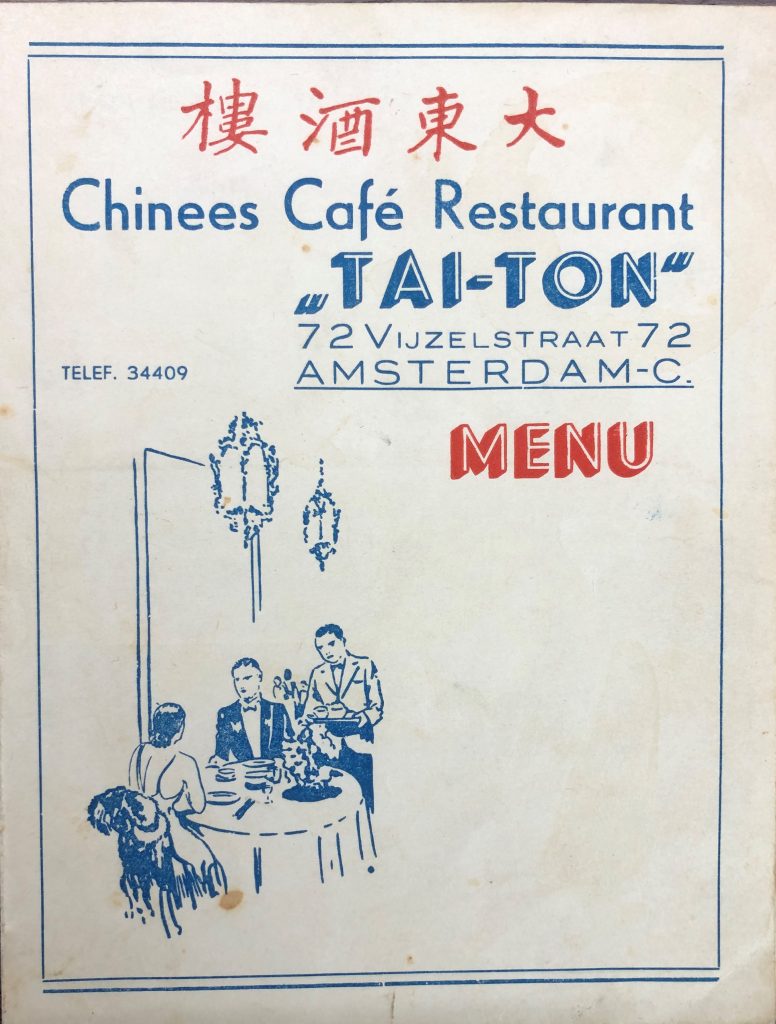

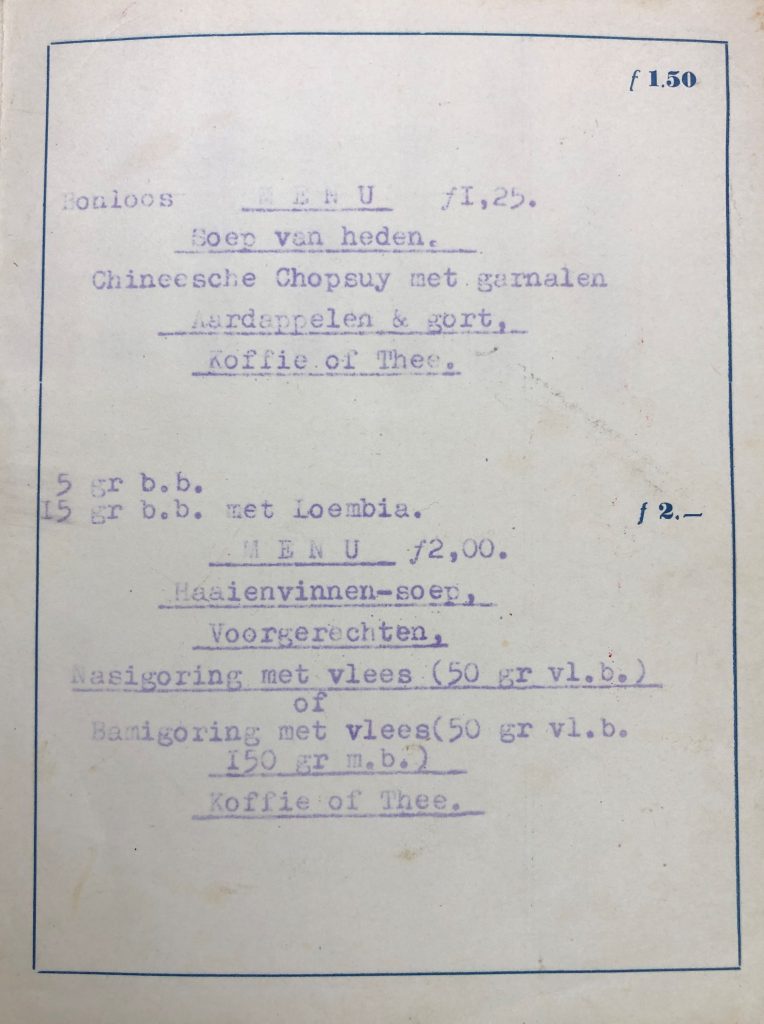

The menu of Chinese restaurant Tai-Ton in Amsterdam featured the dish ‘Chineesche Chopsuy’ (tjap tjoy), which consisted of shrimp, potatoes, and groats – a striking combination of a typical Chinese dish with Dutch ingredients. Notably, the Indonesian dishes nasi and bami goreng were also on the menu, already familiar to some Dutch people at the time. ‘Tjap tjoy’ literally translates to ‘mixed vegetables.’ Allard Pierson, 1943.

Take babi pangang, for example: this dish, which originates from Chinese cuisine, has developed a sweet and crispy variant in the Netherlands that is distinct from its authentic counterpart. Foe yong hai, an omelet filled with vegetables and often served with a sweet-and-sour sauce, is another adaptation that perfectly aligns with the Dutch preference for less spicy and sweeter flavors. Similarly, tjap tjoy, a stir-fry dish combining vegetables and meat, emerged as a dish that combines both Chinese traditions and Dutch eating habits.

This cultural adaptation illustrates how the Dutch have put their own spin on Chinese dishes, leading to the emergence of a wholly new cuisine that is now regarded as typically Dutch. For many Chinese restaurant owners, adapting to the local taste was crucial for survival in a new country, serving as a strategy for success in a competitive market. Through these adaptations, they have managed to preserve their culinary traditions while also responding to the desires and needs of their Dutch customers.

The Rise of the ‘Afhaalchinees’ and Its Enduring Popularity

In the 1970s and 1980s, the ‘afhaalchinees’ became a true staple in the Netherlands. Restaurants specializing in takeout meals sprang up rapidly, offering a quick and accessible way for people to enjoy Chinese cuisine. What made the takeout Chinese restaurant so appealing was the combination of speed, affordability, and generous portions. These factors made it a popular choice for families and working individuals who lacked the time or desire to cook after a long day, or during occasions like birthdays when many guests needed to be fed.

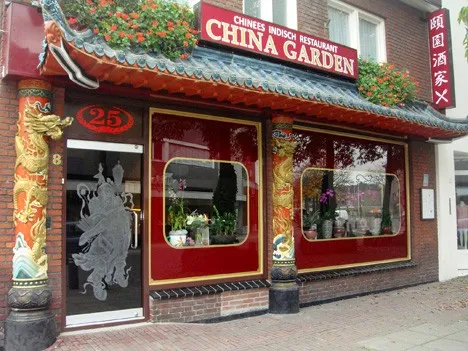

The Chinese-Indonesian restaurant ‘China Garden’ from the outside and its ‘oriental’ looking interior. Similar restaurants have become a familiar part of the Dutch streetscape in recent decades. Chinees-Indisch Restaurant China Garden, 2008.

The evolution of this concept is remarkable: what began as small neighborhood restaurants catering primarily to Chinese immigrants has transformed into establishments accessible to everyone in cities and towns across the country, growing in popularity over the years. By the late 20th century, even a political norm was established, allowing a Chinese restaurant to open in every Dutch city or district with more than 10,000 residents, as set forth by the Ministry of Economic Affairs in 1980. This growth reflects the enduring popularity of the takeout Chinese restaurant within Dutch culinary culture, where it has become a familiar part of daily life. The plastic takeout containers, the ever-present question “Sambal bij?”, the service windows leading to the kitchen, and the quintessential Oriental decor of Chinese restaurants are aspects that every Dutch person recognizes.

A Unique Dutch Fusion

Chinese immigrants and their restaurants have profoundly transformed the culinary landscape in the Netherlands. Through the ‘Dutchification’ of Chinese dishes, unique variations have emerged, such as babi pangang and foe yong hai, which are now beloved throughout the country. You can find ready-made meals like nasi, bami, babi pangang, or saté in every Dutch supermarket. The organization “Meer dan Babi Pangang” works to combat racist stereotypes and highlight role models of Asian descent. Since February 2021, it has even contributed to the inclusion of the Chinese-Indonesian restaurant culture in the Inventory of Intangible Heritage in the Netherlands.

According to them, “babi pangang symbolizes cultural diversity. Three very specific cultures are involved: it is made and served by the Chinese, eaten by the Dutch, and has an Indonesian name. The fact that this unique fusion originated in the Netherlands makes it a part of Dutch heritage.” Despite the increasing number of restaurants featuring various international cuisines in recent years, leading to a gradual decline in the number of Chinese-Indonesian establishments, it is wonderful to see the lasting influence of Chinese and Indonesian culinary traditions on Dutch cuisine. The Chinese-Indonesian restaurant, and with that the ‘afhaalchinees’, is now recognized as part of our intangible cultural legacy, and I hope that Chinese-Indonesian restaurants will always remain a part of our streetscape.

Written by Annemar Renzema