Going to the doctor or pharmacy to get contraceptives is a very natural thing to do today. A hundred years ago, this was not the case, as contraceptives were not widely accepted. Despite these circumstances, Marie Stopes opened the first (free) birth control clinic in London in 1921. The Mother’s Clinic gave women advice on sex and birth control and supplied a cervical cap, designed by Stopes. She is branded as a birth control pioneer. However a careful approach of her positive impact on women’s rights is necessary. There was a dark side to the promotion of this cervical cap, as its history makes clear.

Author: Floor Kleuskens

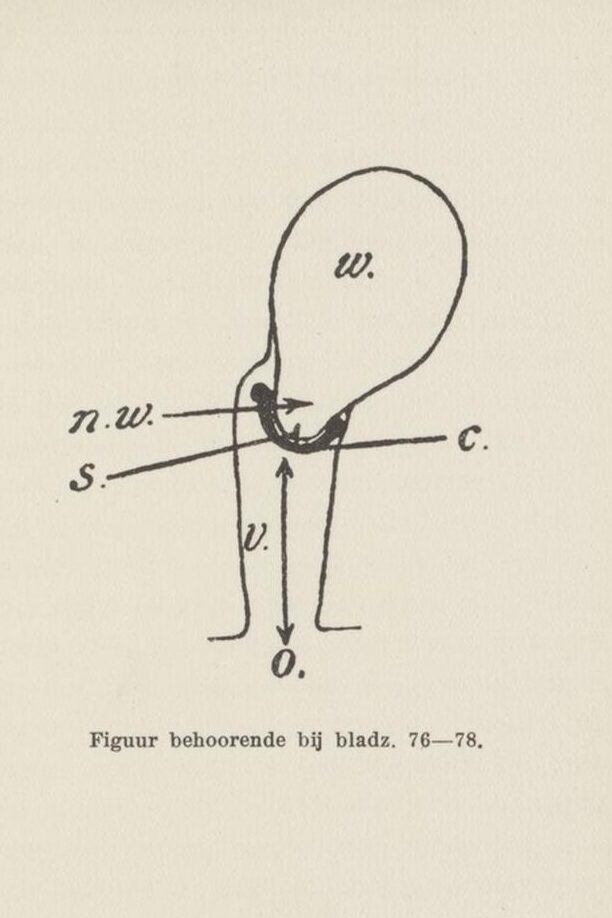

The cervical cap, which is part of the Science Museum Group collection, is a forty by forty-five millimeter cup. The cap is a so-called barrier contraceptive. It is designed to be placed inside the vagina and cover the cervix to prevent sperm from entering the uterus. In Wise Parenthood, a guide about sex and birth control for married people, Stopes writes that the cervical cap is a perfectly safe method of protecting against pregnancy. She explains how to use the device.

“Before insertion the rubber cap should be moistened with very soapy water, so as to allow it to slip in easily […] The great advantage of this cap is that once it is in and firmly and properly fitted it can be entirely forgotten.”

Marie Stopes in Wise Parenthood (1920)

She recommends using a spermicide to prevent accidental sperm cells from entering the womb during removal or slight displacement.

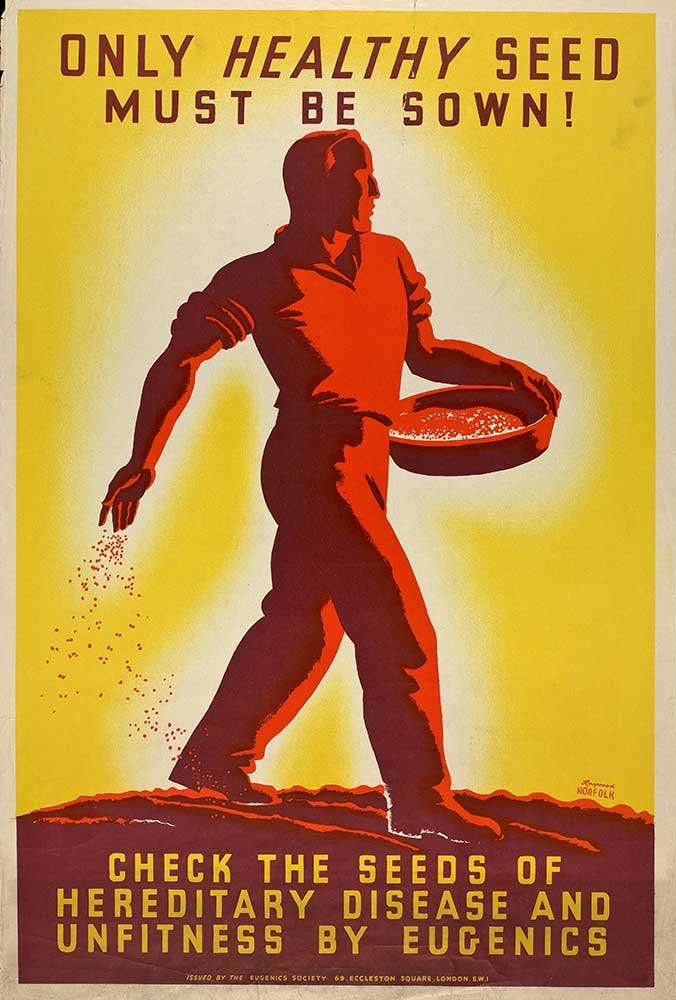

The cervical cap is trademarked by the name ‘Prorace’. This name itself already suggests a dubious purpose of the cap. Stopes’ birth control mission likely sprung from her beliefs in Eugenics. Founded by Francis Galton in 1883, Eugenics was a social movement which aimed to improve human population by selective reproduction. Positive Eugenics meant to encourage the development of desirable populations, while negative Eugenics refers to decreasing unwanted groups or traits. Eugenics was widely accepted in the early twentieth century. It manifested in practices as segregation and sterilization, but also more subtle strategies such as pre-marital health certificates and public health programs.

Birth control vs. population control

Stopes birth control campaign cannot be seen separately from Eugenics. She was an active member of the London’s Eugenics Education Society and defended her ideas about contraception. In a pamphlet Some Objections to Contraception Answered published in 1931, Stopes answered to general Eugenic concerns of birth control leading to ‘racial suicide’. This term refers to the fear of weakening of the dominant ‘race’ due to impure breeding. Stopes writes that using contraceptives, like the cervical cap, will actually prevent such a ‘racial suicide’, because there is already “racial danger of wrong and uncontrolled breeding”. She writes that birth rates in the favorable classes are declining. Without contraception, there is nothing to do about “the growth of a parasitic degenerate population to suck the life-blood from the healthy and responsible sections of the community.” Her campaigning for birth control can be seen as a way of negative Eugenics.

Stopes also found the Society for Constructive Birth Control and Racial Progress (CBC) in 1921. This organization provided communities throughout the whole of Britain with information about contraceptives. Even though Stopes preferred the cervical cap, the organization also produced and distributed their own CBC condoms. Clearly, Stopes birth control campaigns were broad and structured. It is likely that the promotion of contraception was genuinely meant to create better social circumstances. Furthermore, Stopes talked quite openly about sex in marriage, which was unusual at the time. Despite Stopes controversial writings about uses of birth control she has had a great influence on the spread of birth control in Britain, in times when only a few others took on that mission.

Nowadays, Eugenics is not considered a science anymore and is generally frowned upon. Cervical caps or pessaries are still used today. There is a wide choice of contraception available, and women are free to choose which option is best for them. However unfortunately, the debate about women’s fitness to be mothers is still not over. There are still cases in which people are forced to take birth control, because they are seen as unfit for parenthood. Furthermore, it was only two years ago that the Dutch government apologized for the forced sterilization from 1985-2014 which transgender persons underwent who were in transition.

Without its history, it is easy to view the ‘Prorace’ cervical cap as an early product of feminism. Being able to choose sexual pleasure without the risk of getting pregnant unwantedly, is a step forward. It is indeed possible that the ‘Prorace’ cervical cap emancipated women in seizing autonomy over their bodies. That is essentially what feminism is about. However, it should be recognized that the cap was also presented as a means to restrict certain women’s reproductive choices, and that way it did not promote the right to self-determination at all. From this angle, it can also be seen as an object of racial prejudice. This means that the development of birth control quite complex and not one sided.