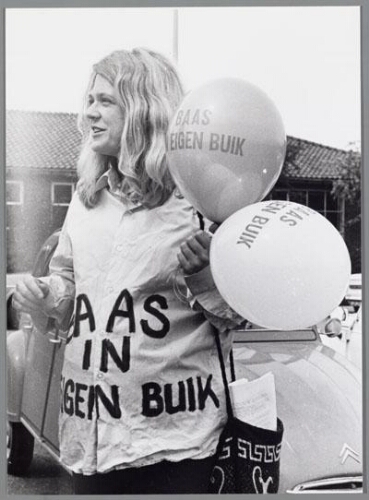

On June 24th 2022, the U.S. Supreme court overturned Roe v. Wade, ending the right to a (safe) abortion as a federal law in the United States. Since then, a total of thirteen American States have restricted or prohibited abortions. The new restrictions range from a stricter time limit on when abortions are legal to a full ban, with no exception for rape or incest. These developments sparked worldwide protests and debates, including the Netherlands. Hundreds of people took to the streets of Amsterdam, showing support for all women in the United States and protesting restrictive Dutch laws on abortion. In spite of numerous banners, posters, and demonstrators, one phrase can not be ignored: baas in eigen buik (freely translated to boss over one’s own belly).

The making of

On March 14th 1970, a group of ten feminists, members of the feminist organisation Dolle Mina, broke into a meeting of gynaecologists in Utrecht but, before doing so, the women wrote baas in eigen buik on their bare stomachs and staged pictures to be taken by a journalist, Jaap Herschel, who had been tipped off by one of the activists. In the black and white picture, you can see five women with the phrase baas in eigen buik on their exposed abdomens. The camera angle is low, just below the hips, so the public looks up to the activists and the women in turn look down on the spectators. The second woman looks straight into the lens with an audacious look on her face. The text written on their bodies is the focal point of the picture. The message could not be clearer: these strong women want agency over their own bodies. The photo was first published in Dutch newspapers, and later the activists attracted attention from abroad. The media and radio in Germany, England, Switzerland, and Denmark offered the outspoken women space in newspapers and time on air. Sixteen years later, the picture appeared in educational history books in the Netherlands and has stayed there ever since.

Photography and media specialists argue that this picture can be classified as an icon because of the frequent distribution; the parodies and imitations that have been produced since the original picture was published and because of the bigger social movement it stands for. The picture, in its early days, reflected the protest in 1970, but over time the picture started to reflect the women’s rights movement as a whole, especially second-wave feminism. Nowadays the picture has its place in the Hall of Fame in the Dutch Photography Museum in Rotterdam. This permanent exhibition shows 99 of the most iconic pictures in Dutch photography from the invention of photography (around 1839) onwards. These pictures are selected due to their impact on Dutch society.

‘Women exposing their bodies. A disgrace in 1970. That’s why this image has been etched into our shared memory.’

The Dutch Photography Museum Rotterdam

Second-wave Feminism

At the end of the 19th century, first-wave feminism came into play. Feminists called for equal voting rights, access to (higher) education and paid labour. In the late nineteen sixties, a second wave of feminism emerged. This time feminists wanted more: equal pay, the right to abortion and equal labour laws. At this point in time, the Dolle Minas joined the feminist stage. Dolle Mina quickly became known for their provoking actions. In 1970 twenty members of Dolle Mina occupied Nijenrode, an educational institute, which only accepted male students. They also burned corsets and interrupted a pageant show as protests against modern beauty standards and female oppression.

The Media Strategy

The Minas had a clear strategy: they wanted to bring as much attention to their mission as possible, be it positive or negative. They found that the best way to achieve this was by shock and provocation, such as the insolence of their first actions. The exposed bellies protest was also one of the first Dutch protests employing the female body. The protest advocated for the right of self-determination, while at the same time also protesting the sexualisation and oppression of the female body. By exposing themselves, these women took back control over their bodies and fought against social standards; they refused to cover up and by doing so reiterated the ownership of their bodies, as something not to be sexualised and regulated by others.

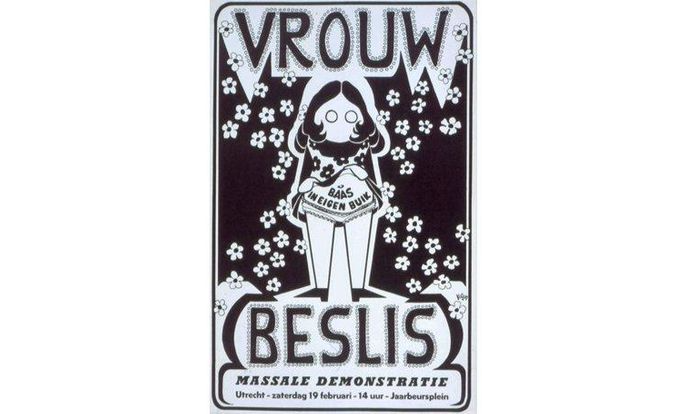

From this point onwards, the organisation embraced the phrase, which they employed in different ways and in different formats to generate an easily recognisable image. It was used for example in a 1972 poster promoting a mass protest organised by the Dolle Minas. This poster, designed by Nel van Beek, shows a woman with the iconic bare stomach and a text above her that says: ‘woman decides’. This way, it is instantly clear what the demonstration is about and who organised it. The picture was also used as the cover of their publication Vijf Jaar Dolle Mina, published in commemoration of their five year anniversary.

According to the activists themselves, the action was a success and the photo turned out to be a great tool for attracting engagement in the future. The Dolle Minas knew how they could generate attention from the media, and how to manipulate this attention to reach their goals and create their preferred outcome. According to one member:

‘The press is exploited by us and, in turn, the press exploits us. We get publicity because of our playfulness and, in turn, this publicity makes us even more playful.’

Irma Bogers, Mannen opzij, vrouwen vooruit? (1983)

The Dolle Minas did not stick around for too long; the organisation ceased to exist only eight years after the photo was taken. It is a shame to see abortion rights being debated and under attack in recent times, even though feminists are still working hard for feminine justice. However, it does show that the battle the Dolle Minas started, should never be considered over. The phrase and the picture will remain iconic and a token of the right to self-determination.

Claire Majoor