‘An army marches on its stomach’, Napoleon once famously proclaimed, or so it is believed. When thinking about war, we usually don’t think about what the soldiers had for breakfast or when their lunch break started, but instead, we imagine fighting armies, bullets whizzing through the air, and tanks rolling into enemy territory. The First World War (1914-1918) was no different, as soldiers of the Allied and Central powers fought a bitter trench war against each other, digging themselves in and engaging in heavy combat over just a few metres of land. But in order for these men to fight, they needed the energy to actually pick up a weapon and run across no man’s land. So, food was an essential part of the war, just like Napoleon claimed.

Food in the trenches

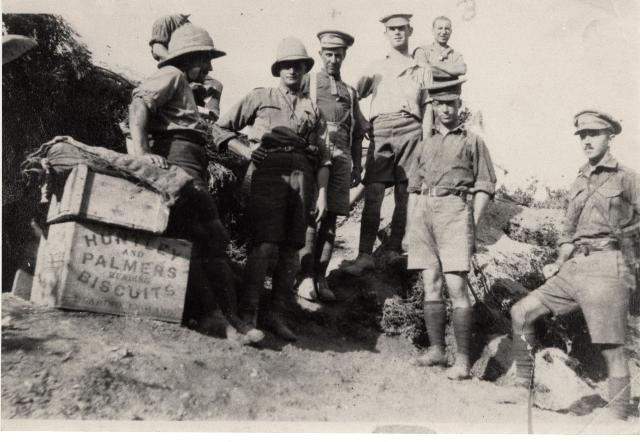

During the First World War, the British Army had quite a practical approach towards food. Its main purpose was to nourish the soldiers and provide the necessary energy for combat. Included in the soldier’s diet were staples like bread, jam and meat and vegetable stews, which were all, as you might expect from the British, supplemented with generous amounts of tea. Behind the front lines, field kitchens were able to prepare hot meals. Some men also received food from home or from local people. Nevertheless, soldiers in the front lines were often worse off, since the conditions in the trenches didn’t allow them to cook any food. As a result, they were left behind with bland and monotonous rations. Particularly important were the tinned iron rations, used on the front lines as a last resort when no external food supplies were available. These rations often included tinned beef, also called bully beef, and, in accordance with British tradition, biscuits.

A British classic: the biscuit

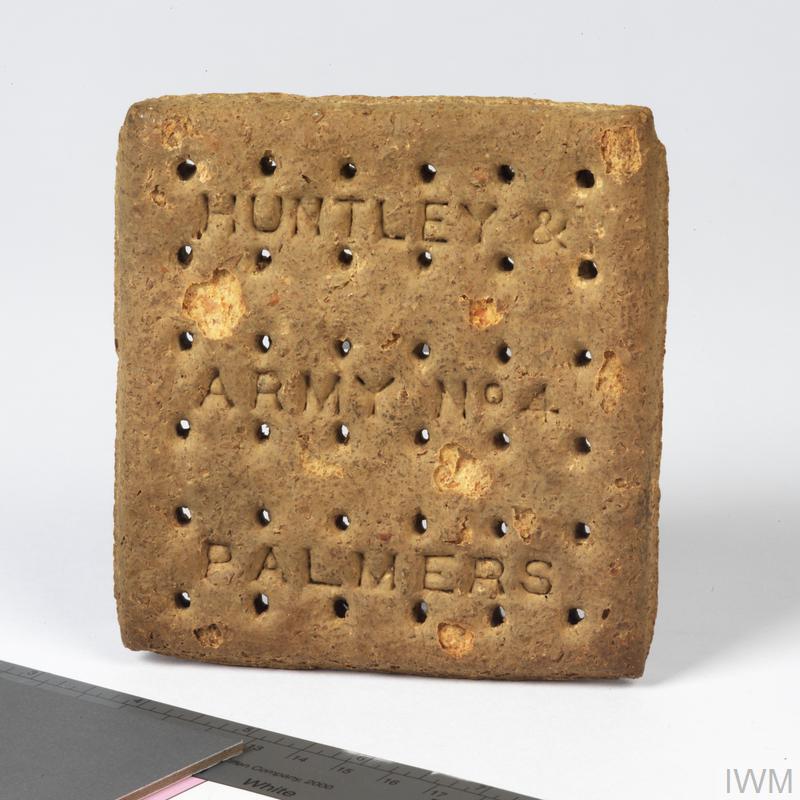

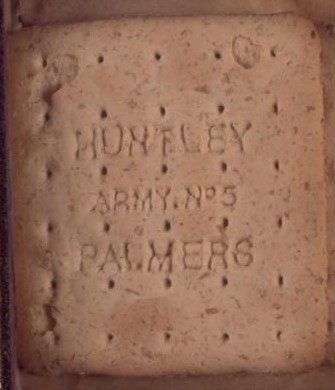

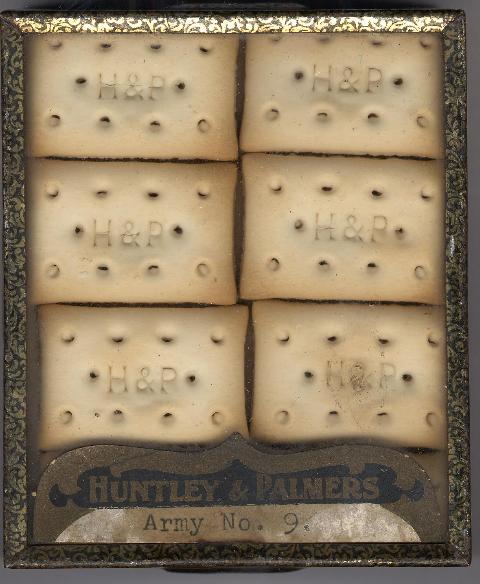

On August 12, 1914, British biscuit manufacturer Huntley & Palmers was ordered by the War Office to make biscuits that were suitable for the army. They needed to be filling, but also durable to survive the terrible conditions of the trenches and avoid any spoilage. So, they came up with the Army Biscuit: a thick, 10-centimetre squared, hardtack biscuit, only consisting of whole-wheat flour, water and salt. The most common one was the Army Number 4, but there were a couple of variations. Until the end of 1917, the Huntley & Palmers factory ran day and night to provide the army their biscuits.

One could imagine that the British soldier was quite happy to see a familiar food so far from home. However, the biscuits were anything but popular. Despite accomplishing the goal of being a filling and nutritional food item, the biscuits were very hard and nearly impossible to eat. To save their teeth, soldiers soaked them in water or tea before eating them, or they mixed biscuit crumbles with water to make a sort of paste, adding this to the weak vegetable soups provided to them. As soldier Ivor Gurney recalled:

‘The Army biscuits suit me. Of course they are too hard for my poor teeth, but hot tea and patience helps one past all.’

Soldier-poet Ivor Gurney, 1915

Getting creative

Because the biscuits proved so difficult to eat, soldiers started to joke around about the alternative ways to use them. For example, soldier Vince Schürhoff, found them to be perfect ammunition during late-night food fights after they had a little bit too much to drink. But others got creative: they started to carve out the centre of the hard biscuits, creating picture frames. Sergeant M. Herring of the Army Service Corps, for example, made such a picture frame and used it to display a photograph of him, his wife and their twins, Barbara and Lawrence. These picture frames could provide a lot of personal value to the soldiers, bringing them a sense of comfort as they could keep their loved ones close to them, even in battle. Another soldier, Private George Mansfield, also made a frame, but instead of cherishing memories of his life back in England, he inserted a picture of himself. He then sent the frame to his family, assuring them he was doing well.

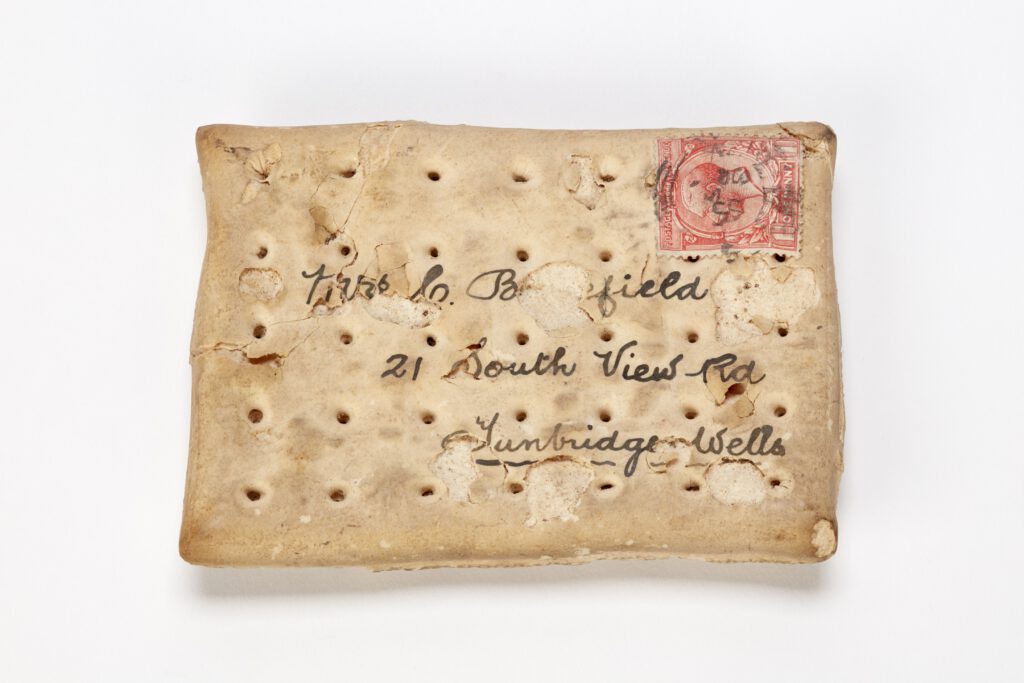

Besides creating picture frames, the biscuits were also used as postcards. Henry Charles Barefield, a member of the St John Ambulance Brigade, sent one back to his family in Tunbridge Wells, adding the following message: ‘Our new rations. Thought you would like one. Gott Straffe G.’ The last phrase was probably a reference to the German saying ‘Gott Strafe England’, or ‘May God punish England’. Here, Barefield substituted ‘England’ for the ‘G’ of Germany. On the back of the biscuit he wrote an address, which even included a stamp!

‘Have gone on hunger strike, reason attached, mind your toes.’

A British soldier during the First World War

Others simply sent the biscuits back home as a souvenir to share some of the daily experiences of the front, mockingly expressing their dissatisfaction with the army rations. For instance, a biscuit was sent back by a soldier with a note saying: ‘Have gone on hunger strike, reason attached, mind your toes.’ Another soldier, Private Alfred Jackson, wrote on his biscuit: ‘Our motto. Your king and your country need you and this is how they feed you. Bow. Bow.’ It is unclear, however, if he sent it back home, or if he just kept it as a souvenir for himself.

The biscuits, then, proved to be much more than just a way for soldiers to hit their daily 4000-calorie intake and maybe break a few teeth in the process. The unfortunate quality of the biscuits also resulted in an unexpected, but welcome consequence for the soldiers: through the creative uses of the hard biscuits, they could now cherish family memories while on the front lines, or share a small part of the war experience with loved ones back home. It thus became a versatile food source, providing both nutritional and emotional value to the soldiers fighting in the trenches between 1914-1918.

Written by Carolien de With