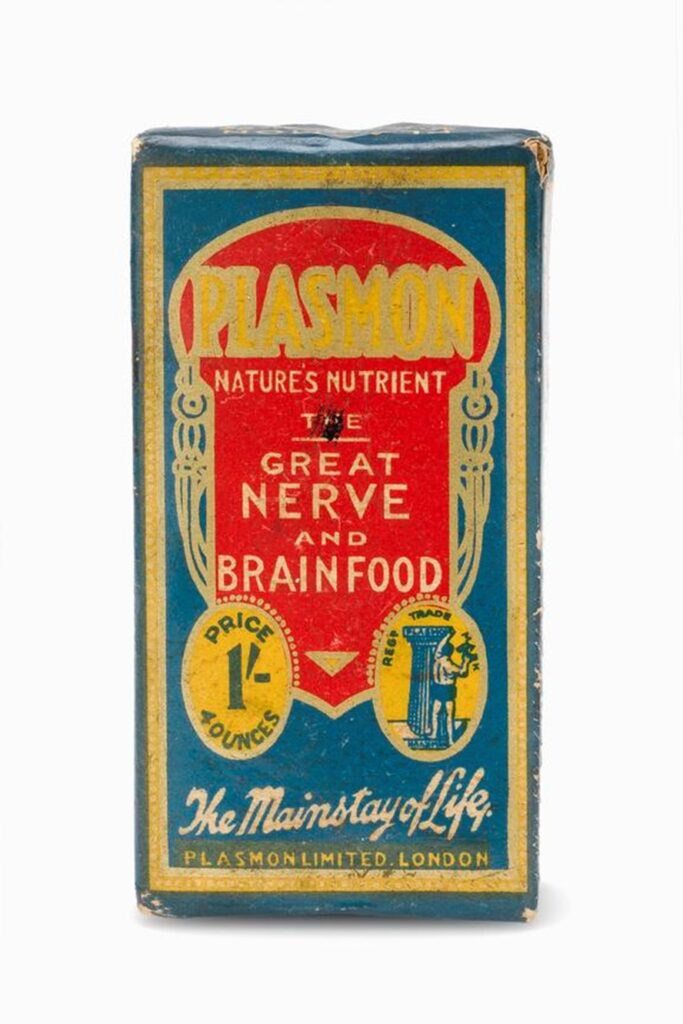

It’s just a tiny carton box, one so small that you could probably carry it in your pocket without noticing it´s there. Yet, it is full of promises. The words on the cover that lure you in suggest that whatever is inside this box will connect you to nature, improve your mental capabilities and, last but not least, give you the opportunity to look like a Greek god for little money and little effort. What is this wondrous substance, you ask?

1950 by Plasmon International. Science Museum London.

It is Plasmon, the milk protein powder that transformed notions of what a ‘health food’ could be, laying the groundwork for modern fitness food trends before Arnold Schwarzenegger or the Rock even became a thing. This particular box is made in London, where it was originally produced by the International Plasmon Company. Now, the package is on display in the Science Museum, forming a part of the ´Who Am I? Gallery’ that showcases objects ‘of human ingenuity and scientific achievement’. This is fitting because Plasmon, as a wonder food, can be seen as a symbol for a time wherein nutrition and scientific progress became intermingled.

Plasmon´s Origin Story

In the late 19th century, the Swiss chemist Siebold created what would later become Plasmon. During this time, many scientists tried to come up with ways to reduce food waste; in this case, skimmed milk waste. Siebold eventually came up with this white, isolated protein that was completely without taste and odour. Boring, you might think. Well, with the help of some German scientific experts who underlined the nutritional value of the powder, Siebold managed to sell the license to a group of investors in London. These investors sold it to a company that quickly became popular in Britain: the Plasmon International Company. Among the investors was one man you might have heard of: Mark Twain. He, not only author but also questionable businessman, had such high hopes that he suggested the powder could ‘end the famine in India’.

Scientific ideals, encapsulated in a protein powder

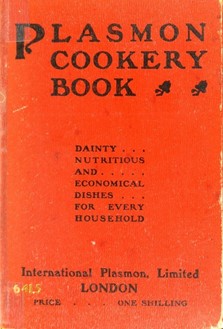

Plasmon approached the powder as a blank slate upon which all sorts of marketing strategies could be projected for various audiences. Because of its versatility, the company created all kinds of products containing the powder, such as cocoa, porridge, pasta, and, most famously, the Plasmon biscuit. Consequently, Plasmon started to appeal to normal households. Using the powder was, after all, a simple way to consume nutrient-dense foods without having to spend much time, effort and money on cooking.

This Plasmon ‘cookery book’ is an example of how the company tried to appeal to regular households. It contains ‘ordinary household recipes’ for daily use. This edition stems from 1904 and comes from the library of the University of Leeds.

Historian O’Hagan claims that to strengthen its marketing, Plasmon International relied on scientific language and data. By using an appeal to authority, the company made strong claims about the product´s benefits for growth and vitality. However, the product also faced some scrutiny, as some researchers and scientists claimed that Plasmon did not have extra nutritional benefits at all. So, next time you buy a protein shake or bar that claims to drastically improve your life, you may want to look at the research!

Plasmon: Made for the Modern Man?

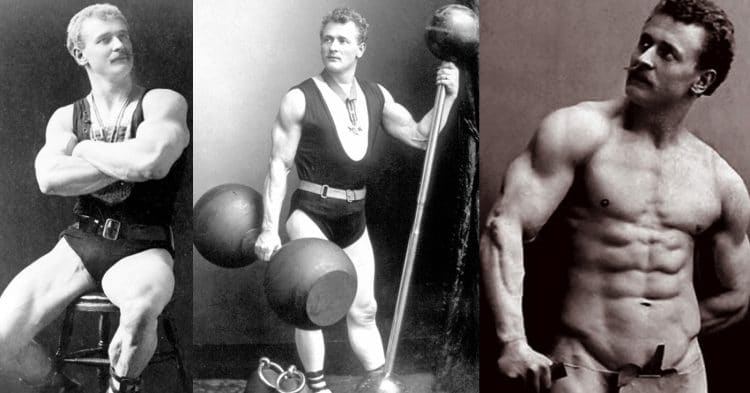

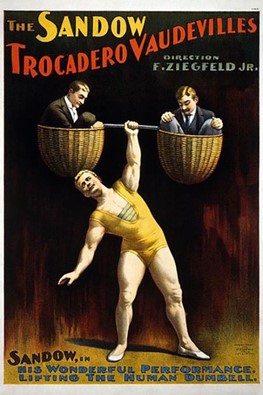

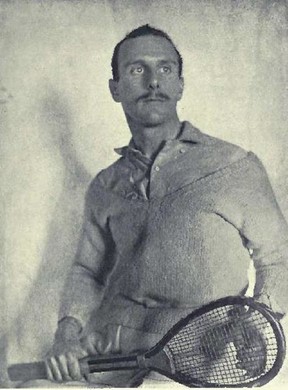

The main audience Plasmon appealed to, however, wasn’t made up of housewives who wanted their children to grow faster. No, Plasmon grew popular because of its associations with the Physical Culture Movement (PCM) that came into fruition in the late 19th century. Plasmon was endorsed by the fitness gurus of the time: the masculine ‘father’ of bodybuilding Eugene Sandow (shown in the feature image), and the slightly more feminine, gentle-looking tennis player Eustace Miles, who advocated for a vegetarian diet and later went on to advertise other protein powders and fad diets.

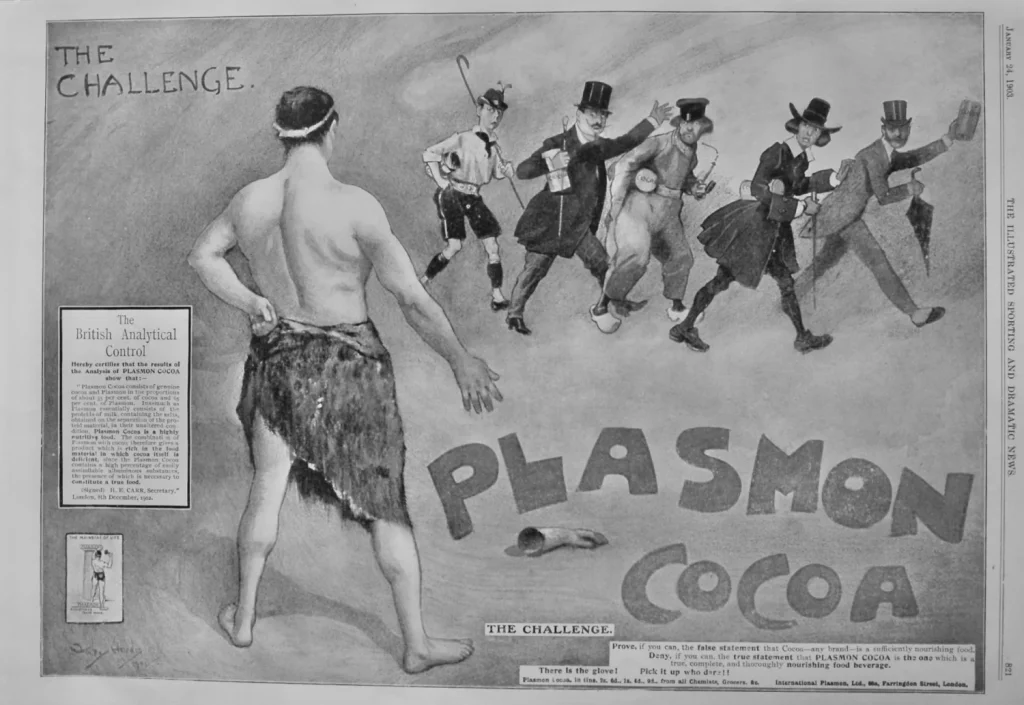

The promise that consuming Plasmon would make you more muscular and masculine is clearly reflected in a lot of the advertisements for Plasmon’s products. Below is one example: the Plasmon cocoa consumer is represented as a caveman-like figure, surrounded by meak urban bystanders. Here, Plasmon’s claim that it is ‘nature’s nutrient’ is also implied in the male figure. He, after all, is connected to his roots or nature through his masculinity.

The Backlash:

Despite its popularity, Plasmon was also subjected to scrutiny, as some news outlets such as The Daily Express and satirical magazine Punch made fun of the powder. For Punch, the main source of ridicule was Eugene Miles. The historian Steinitz states that Miles may have made an interesting target because of the milder kind of masculinity he represented. A man with a slight body and interest in vegetarianism? How alien and outlandish!

“Every housewife should study Eustace Miles’ fascinating article on How to live on two Plasmon biscuits and one lentil a day, which appears in the Report of the Royal Commission on Physical Deterioration’’

(Punch Magazine, October 26, 1904, vol. 127)

In some ways, the reception of the powder even mirrors current debates about health foods! By looking at the popularity of Plasmon, it can be seen that some people really invited the idea that your life and health could drastically change by simply consuming one wonder powder. Others, however, hesitated to accept it as part of the regular British diet. Instead, they approached Plasmon with skepticism about its scientific claims or they viewed it as a temporary rage for the vain and idle-minded.

The Legacy of Plasmon

It is not entirely clear why, but in the lead up to and after the Second World War, Plasmon began to lose its popularity. The company finally ceased to exist in Britain in 1962. O’Hagan claims that Plasmon might have become unpopular since its marketing stopped appealing: in the 1930’s, ideas of the ideal male masculine body became associated with Fascism and the far right. Maybe, people just began to take in more protein in their daily foods, without having to resort to a powder. Nevertheless, what is clear is that some of the marketing strategies that Plasmon used are still prevalent today in protein powder foods, in the form of appeals to authority and masculinity:

Whilst Plasmon’s history might have been forgotten in Britain, products and marketing strategies that look remarkably like those of Plasmon are still present, invoking reactions and debates up until this day. This only goes to show that the company’s legacy, like so many examples in the history of food, has changed and adapted through time and space, still continuing to do so.

Written by Marije Huging