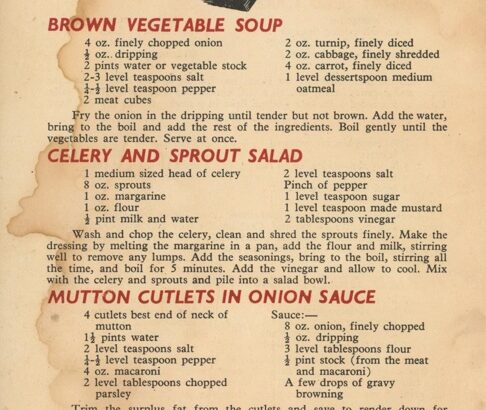

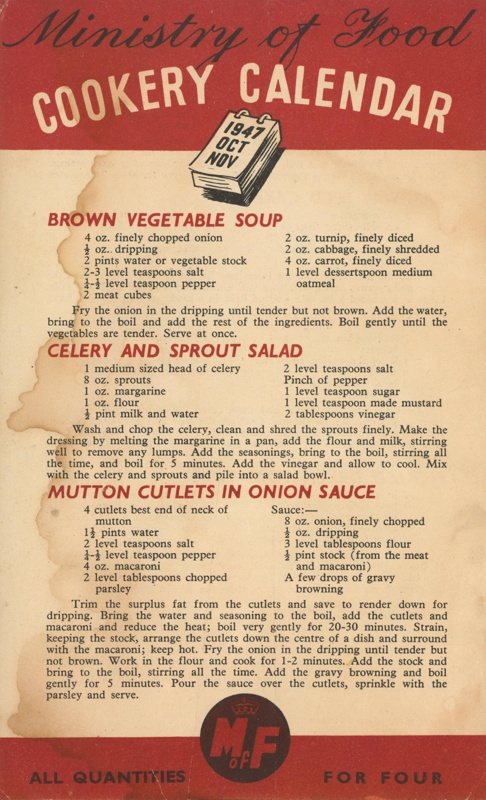

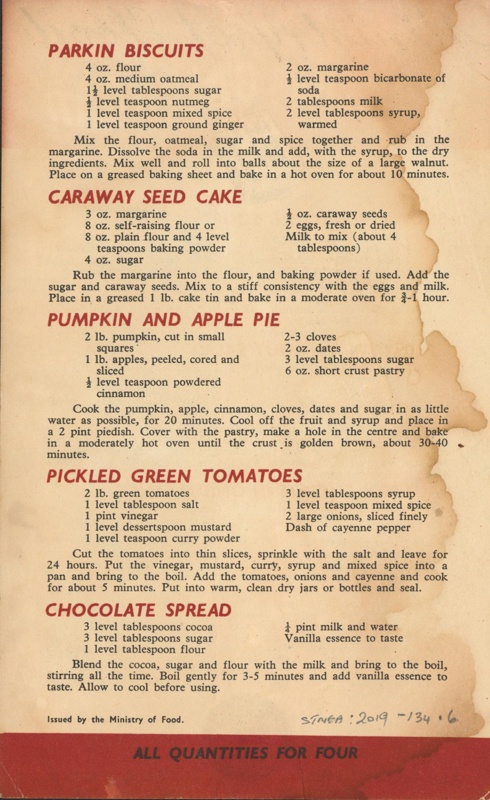

Brown vegetable soup, celery and sprout salad or pumpkin and apple pie. Does this sound tasty to you? The recipes are from the Ministry of Food cookery calendar. These recipe advice sheets were issued bi-monthly in an effort to assist and improve diets during food rationing following World War Two. The cookery calendars were part of a larger set of instructions, brochures and pamphlets issued by the Ministry of Food. The main purpose was to reduce waste and make the most of scarce resources. Nowadays preventing food waste is a hot topic again as a means of combating climate change. Back in the 1940s concerns about food scarcity spurred action. How did the British government and the citizens deal with food austerity at that time? And why did the rationings continue after the war?

Rations during and after the war

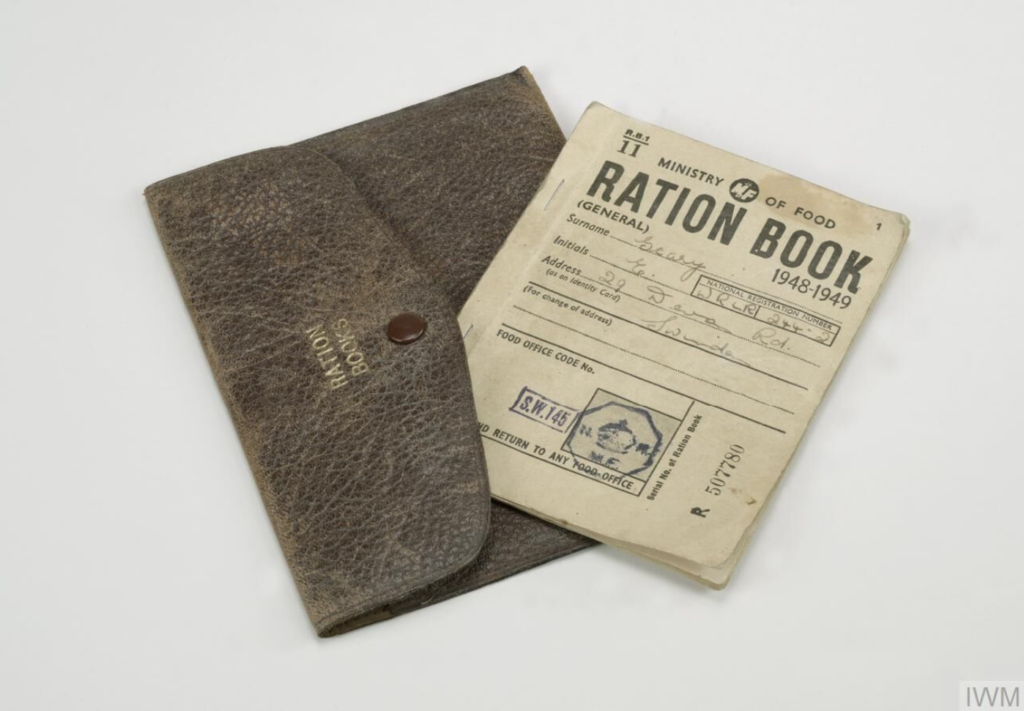

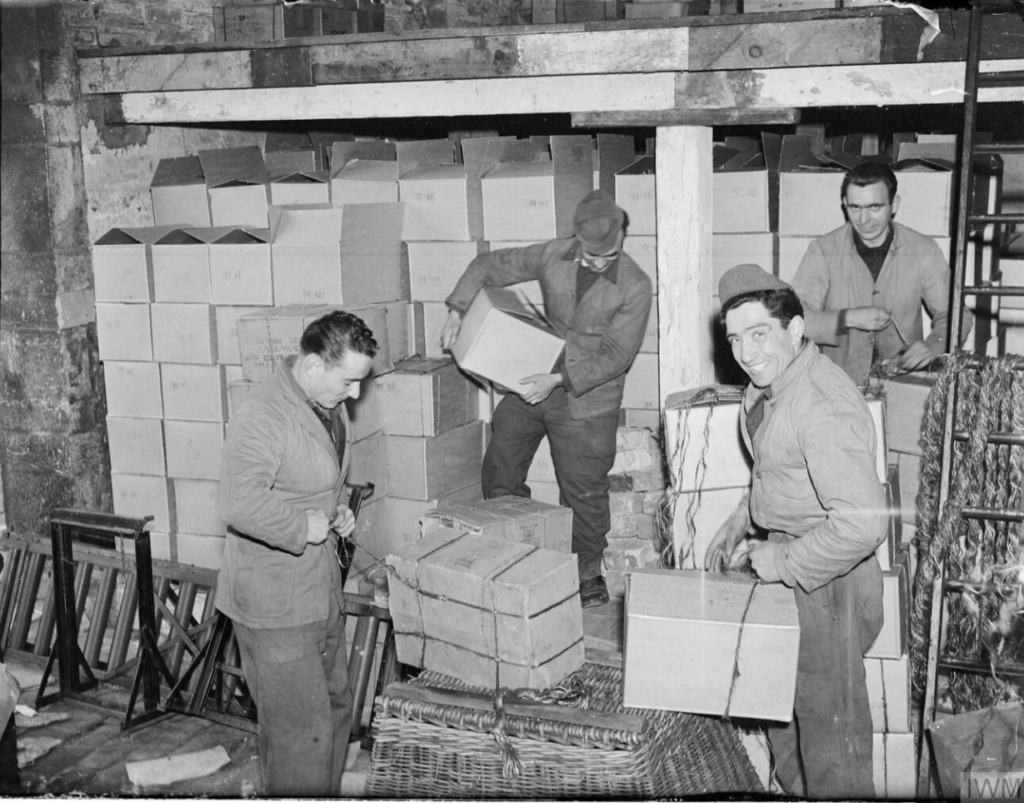

The British experienced some sort of food rationing before, during the First World War. With that in mind, the government started as early as 1936 to make plans for the supply, control, and distribution of foodstuffs. Britain was at that time a net-importer of food, so if the supply decreased, this could be potentially devastating. As recently experienced during the covid crisis, when people fear scarcity, they start hoarding in panic. With a fleet of German U-boats in the sea as a weapon to starve the nation into defeat, concerns about food scarcity were very justified. So, to prevent a catastrophe the first foodstuffs were rationed in January 1940: bacon, ham, butter, and sugar. Other products, such as meat, cheese, margarine, eggs, milk, tea, breakfast cereals, rice and biscuits soon followed. By mid-1942 most foodstuffs were rationed, except fresh vegetables, fruit, fish, and bread. The Ministry of Food, that was constituted at the outbreak of war in 1939, was responsible for overseeing rationing. Every citizen was given a ration book with coupons. These needed to be handed in at specific local shops to receive the rationed goods.

The food rationings didn’t stop with the end of the war. In fact, some aspects of rationing became even stricter than during the war. Just a few weeks after the victory cookery fats and meat rationings went down. Bread, that was un-rationed in the wartime years, was rationed from 21 July 1946 to 24 July 1948. The winter form 1946-1947 was very cold and destroyed a huge number of stored potatoes. That leaded to the rationing of potatoes in 1947. The cookery calendar from October/November 1947 shows the impact of these rationings. The recipes consist of a lot of fruit and vegetables, products that weren’t rationed at all. Potatoes do not occur in the recipes. Instead, there are for example recipes for soup, salad, and macaroni. Apart from the ingredients, the recipes were especially distributed to learn people to measure their food well and to make a balanced meal so that nothing was wasted. Decontrol of food started in the late 1940s, but it was not until July 1954 that the last food, meat, was derationed.

Continuation and controversy

The reason that was at first given for the continuation of rations was that spare food would be better directed to countries in Europe like Holland, Belgium, and Denmark where food shortages were much higher. Another reason for the continuation of rationing was the curtailment of financial support from America, which meant Britain still could not afford to import the same amounts of food that it had done before the war. Britain had high debts after the war and the Labour government who was appointed in 1945 committed to socialist planning to counteract the economic crisis. Despite economic recovery in the late 1940s, further crises like devaluation in 1949 and the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950 which contributed to high inflation made the dismantling of rations difficult. Controls of consumption had become an integral part of Labour’s approach to post-war reconstruction which prioritized exports, investment, and collective provision.

This policy became increasingly controversial during the late 1940s. Despite some difficulties, overall food morale was maintained during the war. People excepted the necessity of rationings and food control. This changed after the war. The introduction of bread rationing represented the height of post-war austerity and involved a severe blow of the morale. People felt discontent about the diet, which they believed was inadequate to keep them in good health. Especially women were increasingly dissatisfied with the rationings, as they were most directly concerned with the rations. They were frustrated by the food queues and the difficulties of preparing a meal for the family out of diminishing rations. Handing out recipes in cookery calendars didn’t help anymore at that time to comfort the housewife. Historian Ina Zweiniger-Bargielowska argues that by fostering these sentiments and claiming that they will make an end to rations, the conservatives won the general elections in 1951.

Diet inspiration

The cookery calendar demonstrates that the Second World War had a long-lasting impact and food scarcity stayed a problem for years. This impacted everyone in society and people had to make the best of it. The wartime food scarcity eventually brought about something good, because the food rationings forced people to adopt new eating patterns. Although the measures were born out of necessity, the rationings helped the British to get healthier than they had ever been. Most inhabitants ate less meat, fat, eggs, and sugar than they had eaten before. On the contrary, poor people who previously couldn’t effort to buy good, healthy food were able to increase their intake of protein and vitamins, because they received the same ration as everybody else. Moreover, young children, expectant and nursing mothers were given extra food. As a result, the general health of children improved, infant mortality rates declined and the average age at which people died from natural causes increased. So, if you are looking for a new diet, check out the recipes of the British Ministry of Food. Maybe history can make you healthier.

Want to learn more?

Zweiniger-Bargielowska, Ina, Austerity in Britain : Rationing, Controls, and Consumption, 1939-1955 (Oxford 2000). This book gives a good overview of rationing policy and popular attitudes and connects this with party politics during and after the Second World War.

If you are interested in the taste of some of the food options for those on the home front in Britain during the Second World War, popular historian Dan Snow experiences some of them in this video.

Written by Nina Cornielje