As a political science student, I wrote my bachelor thesis on the foundation of a national slavery museum in Amsterdam. Focusing on the difficulties that arise in this process, I was mostly touched by the way in which we do not seem to be able to engage with the history of slavery as a shared past. Given the colonial origin of the Tropen Museum, I find the permanent exhibition ‘The Afterlives of Slavery’ a very noteworthy and important effort made. I would argue that a former colonial institute taking a stand like this is an essential step towards an inclusive understanding of our history.

History of the Tropen Museum

Starting off as a museum focused on the Dutch colonies in 1864, the Tropen Museum went through several transformations throughout the years. Until 1923, it was the only colonial museum worldwide. A large part of their collection originates from that period of time. After World War II, the museum changed its name from ‘Colonial Museum’ into ‘Tropen Museum’. Due to the new name and aim of the museum, the collection had to be thoroughly revised. Nowadays, the Tropen Museum is ‘a museum about people’ that attempts to make its visitors curious about the rich cultural diversity of our world. “In the Tropen Museum, one discovers that besides our differences, we are all the same: human.” Throughout the past decade, the Tropen Museum has tried to transcend the focus on colonial heritage and put the emphasis on the equality of all human beings. This revision of their public image and mission has, amongst other things, led to the development of the permanent exhibition ‘The Afterlives of Slavery’.

A conversation starter

This exhibition was developed by Richard Kofi, Wayne Modest and Martin Berger. In this process, they cooperated with various other experts on the topic such as The University of Colour, Decolonize the Museum and New Urban Collective. The exhibited objects were supplied by The Black Archives and the Tropen Museum itself. Amongst other things, in the original collection of the Tropen Museum, the curators found stamps that were used to brand enslaved people with. Together with original receipts and testaments of slaveholders, the exhibition confronts its audience with the horrors of this history. However, confrontation does not seem to be the primary goal of its makers. Most importantly, the exhibition informs its audience on the social structures that enabled the system of slavery to exist and the ways in which colonial thought is part of our society today. It engages with contemporary stereotypes of black people and discrimination in the labor market. I would argue that this exhibition is not about pointing fingers. From what I have seen, its main goal is to raise awareness for a shared history and to start a conversation.

Connecting people with a history of resistance

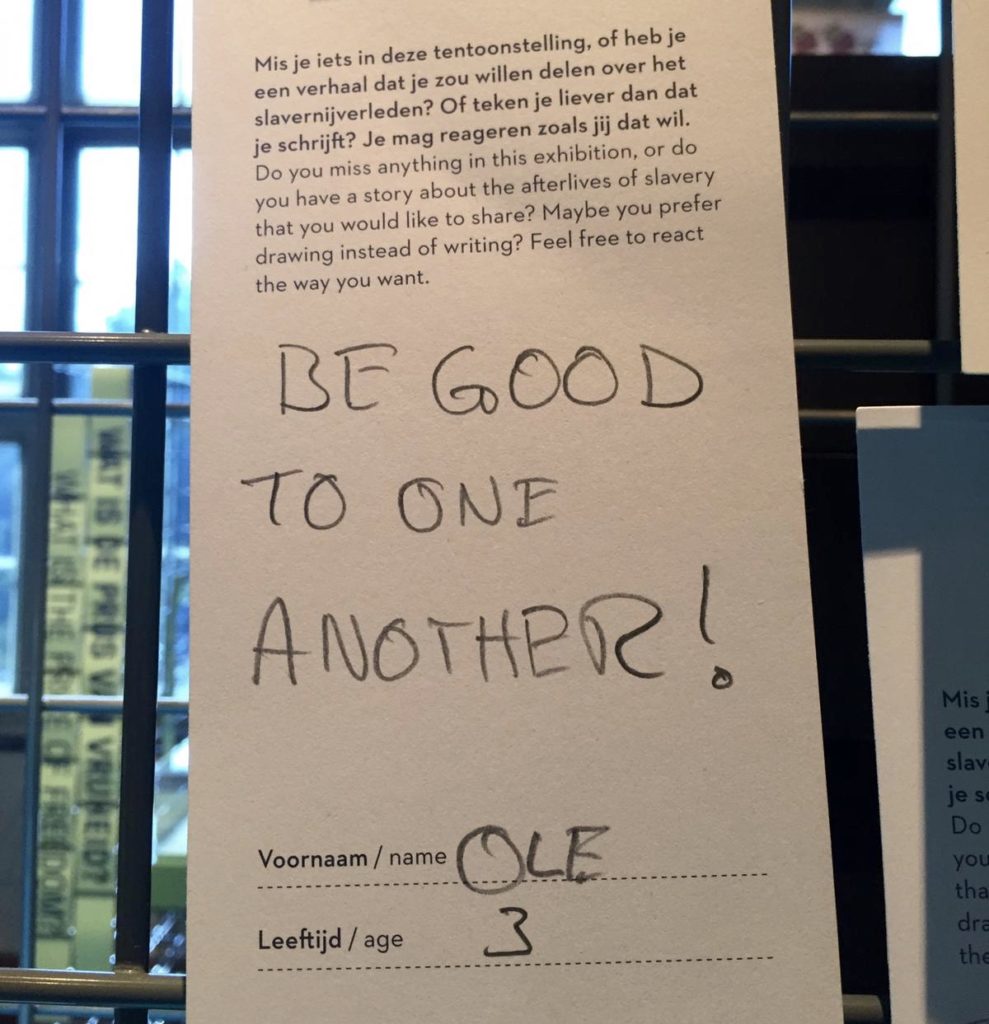

Notwithstanding the exhibition’s rich and broad content, the following aspects most explicitly stood out for me: the presence of perceptible faces to the story, the focus on resistance and the opportunity to participate. First, the audience is introduced to the topic through spoken word. By addressing the audience directly, we are reminded about the emotionality of this history in present-day life. In my experience, these performances made a very big impression. Following, we have the opportunity to learn about the history of slavery through video’s of experts. Here, I believe the makers added a very important humanizing aspect to the exhibition, connecting present-day faces to the inheritance of slavery. Second, the exhibition explicitly focuses on the resistance by enslaved people instead of their oppression. On one hand, the makers thereby emphasize the agency of the enslaved; an empowering way to address this topic. On the other hand, in doing so, I believe they avoid pointing fingers and try to keep every member of their audience engaged. Learning about this part of our history through the eyes of experts gains this exhibition a lot of credibility. The experts emphasize a system of power in which slavery could exist. It does not point fingers in the direction of black or white. Instead, it raises awareness of the ways in which we are all part of this system. Most of all, I appreciate the interactive aspect of the exhibition, in which visitors have the possibility to leave comments, thoughts or feelings on a wall. The audience is invited to participate in the exhibition, and thereby also to take part and engage with this history as a shared one. Through this wall, the makers enable their audience to reflect on their own position and connect with this part of the past.

Beyond ‘us’ and ‘them’

This exhibition presents the history of slavery as a shared history. Meaning, a history which both black and white people have been part of. Often, we tend to forget that engaging with the history of slavery can be about engaging with a destructive system of power, which we are all part of. Do we really need to speak in terms of a black and a white perspective, us and them? I would argue that it is time to move beyond this division and towards a shared understanding of our history. I am often disappointed by the ways in which we are, most of the time, lacking the means to engage with our past. However, at the same time, I am impressed by the way in which a former colonial institute like the Tropen Museum is trying to provide a platform in which we can learn and move beyond ‘us’ and ‘them’.

Sezen Moeliker

Links:

https://www.tropenmuseum.nl/nl/themas/geschiedenis-tropenmuseum

https://www.volkskrant.nl/nieuws-achtergrond/musea-dekoloniseren-richard-kofi-hervertelt-de-slavernijgeschiedenis~bb645303/