Visiting the Kruisgebouw in the Dutch Open Air museum (Nederlands Openluchtmuseum) brings you back to the 1950s including smells of the disinfectant Lysol and sounds of children crying and people bathing. Besides, this building is also part of the educational program Canon van Nederland in which fifty vensters make up the Dutch history that is taught in primary and secondary schools. In the museum different sites are linked to one of these vensters, but how does the Dutch Open Air museum succeeds in both giving visitors an experience connected to health and wellbeing and educating visitors according the educational program?

‘Do you remember this?’

Photo credits: M. Bleeker

The history of the Dutch Open Air museum dates back to the beginning of the twentieth century. Since the Industrial revolution, rapid developments changed society and fear of losing traditional buildings and crafts became an issue. That brought the idea to save that heritage and an association was founded to collect buildings that would be removed elsewhere in the country. By 1918, enough buildings were collected to open a museum. Since then, the museum underwent changes and nowadays it does not only focus on living in the countryside but more on the culture of daily live including health and wellbeing.

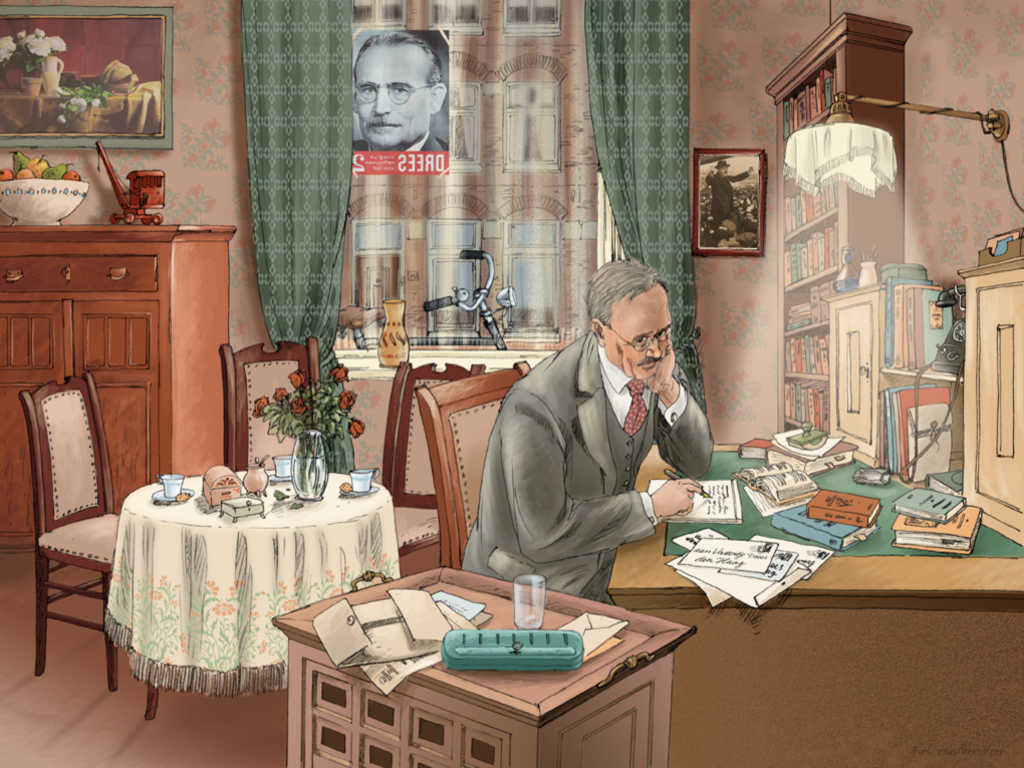

The one building in the museum that is dedicated to the theme of health and wellbeing is the Kruisgebouw. This building was originally build in Wessem in 1954 and like many other kruisgebouwen across the Netherlands it employed nurses and doctors who were responsible for different kinds of health care on local scale, such as nursing the elderly and providing preventive care against tuberculosis. The Kruisgebouw was placed in the museum as a gift from the foundation ‘museale presentatie kruiswerk’. This building was broken down in thirty pieces to rebuild it in the museum in 1998. The interior shows the situation as it was back in the 1950s including a full supplied kitchen, a nun with solex in front of the building and a doctor in his consulting room. People who lived back then recognize a lot of things and ask each other: ‘do you remember this?’ or ‘do you still have these kinds of things?’. Younger visitors think it is funny to see and ask questions such as: ‘is that a real human?’ and ‘was it really like this?’. The building gives visitors the full experience and different reactions can be noticeable during their visit at the building. On the one hand, people leave the building early because they cannot deal with the smell of Lysol and on the other hand people tell each other that they think it is very well done.

Although, the building gives a full experience and kind of time travel, it is very suitable for education purposes. Fully equipping the building with objects from the 1950s shows what was used in that time and the museum did that in quite an interesting way for the medical instruments. Instead of writing down which medical instruments were used for what purpose, they made see-throughs in which visitors could see cartoons in which the action is shown. While walking around the building the first time people did not really use the see-throughs but the second time I saw people really taking time to watch and discuss it with each other.

Education about the Dutch welfare state

Credits: https://www.entoen.nu/nl/willemdrees

Since 2011, the education program Canon van Nederland was implemented in the museum. The fifty canonvensters vary from the Roman limes to the television and give an overview of the Dutch history. For the museum this means that different buildings all across the museum are linked to one of these vensters. The Kruisgebouw is one of them and is connected to the venster of former prime-minister Willem Drees. Different topics are connected such as the rebuilding after World War II, the foundation of the welfare state and the socialist idea of representing the workers.

The connection of the Kruisgebouw with the canonvenster of Willem Drees is made visible at the building itself. Outside the building information is given about the historical background including ‘vadertje Drees’ (daddy Drees) as the simulator of preventive health care in the after war period. Inside the building, in the sphere of the interior, an original movie is playing about the importance of the associations that were connected to the kruisgebouwen including Drees proclaiming to become a member of one of these associations.

Succeeded?

In conclusion, the Dutch Open Air museum does a lot to connect the buildings within the museum to the Canon van Nederland. This is not only done for the Kruisgebouw but for 24 buildings in total. However, the subject of health and wellbeing is only represented in the Kruisgebouw. Besides, the way in which the educational aspect in the Kruisgebouw is organised is done in a nice way, on the one hand information is given about how such a building worked including the medical instruments and on the other hand a deeper historical background is given by the implementation of the canonvenster of Willem Drees. So while getting the full 1950s experience a possibility is created for visitors to learn about the foundation of the Dutch welfare state and about the way health care was organised in the 1950s.

Myrthe Bleeker

Further reading about the kruisgebouwen and its associations: H. van der Boom, et al., ‘Een schets van de professionalisering van de wijkverpleging in Nederland in de laatste vijftig jaar (1950-2000)’, Gewina/TGGNWT 27 (2012) 2: 100-119.