By Hanna Jaspers

Besides the famous Nirvana song Pennyroyal tea, pennyroyal did not mean much to me two weeks ago. As you might know, Kurt Cobain sings movingly: “Sit and drink Pennyroyal Tea. Distill the life that’s inside of me.” Kurt Cobain refers to the fact that in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, pennyroyal was widely known as a potential abortifacient in many English-speaking countries.

An abortifacient is a substance – for example a drug – that is known to induce abortions. This specific box is in the archive of the Museum for Abortion and Anticonception in Vienna. It has been in their collection since 2013, although it is not on display. Pennyroyal is a herb that belongs to the mint family and is also used as an insect repeller. Pennyroyal was also often consumed as tea, just like Kurt Cobain mentions. In the Atlas Mountain and Cyprus, the herb is still used in traditional medicine.

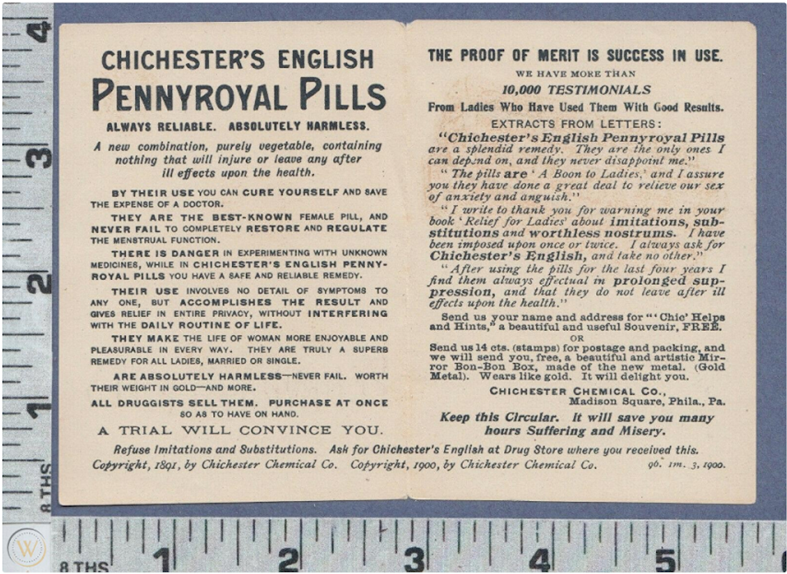

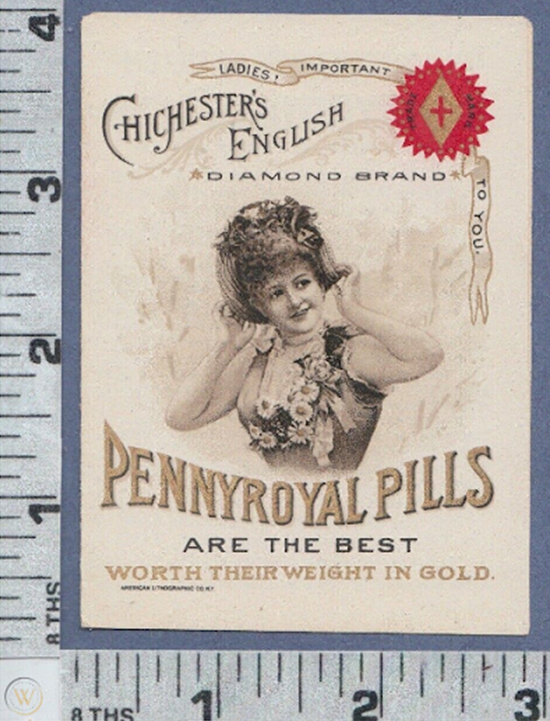

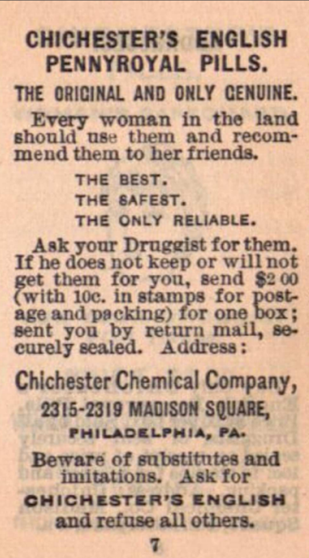

The red metal box contains Pennyroyal Pills by the brand Chichester’s English, located in the U.S.A.. Pennyroyal pills are also known as “female pills” or pills for “female trouble”. These are mysterious, cryptic names for pills. The text on the outside of the box does not tell us much. Only inside, next to the figure of an angel, is a description about what the pills do: “are the most powerful and reliable emmenagogue known. The only safe sure and always effectual remedy in suppression (stoppage) of the menstrual function”. Now we know more. Emmenagogues are herbs that stimulate blood flow in the pelvic area and uterus: some also stimulate menstruation whereby potentially terminating a pregnancy. There is also a figure of a moon, which can be seen as a reference to menstruation: the menstruation cycle is often speculated to be influenced by the moon cycle.

Pennyroyal has a long folk history. People have relied and worked with herbal medicines for may centuries. In the ancient Greek play Peace – which was presented 421 B.c.E., Hermes gifts Trigaius a woman. Trigaius proceeds to ask whether it would be a problem if the woman became pregnant. Hermes replies: “Not if you add a dose of pennyroyal.” The public often laughed at this part, which shows that many people knew about the use of pennyroyal as an abortifacient. Between 1171-1193, Ibn Al-Jami wrote The Book of Right Conduct Regarding the Supervision of the Soul and Body. He advocated for the use of tampons carrying pennyroyal as contraception.

Hermes replies: “Not if you add a dose of pennyroyal.”

However, pennyroyal is also a toxic substance. Claudia Grammer works at the Museum for Abortion and Anticonception and she told me that already in 1925, Dr. Louis Lewin reported deaths of women who used pennyroyal to end their pregnancies. High doses of pennyroyal cause multisystem organ failure. Medical professionals also question whether pennyroyal even works as an abortifacient. The widespread use of pennyroyal in the early twentieth century suggests there were some success stories. So while pennyroyal might terminate a pregnancy, it also harms women in the process, sometimes even resulting in death.

Since the pills are no longer available, it is impossible to determine whether the Chichester’s English pills actually contained pennyroyal or were simply branded as such. In the late nineteenth century, branded medicine was on the rise. Chichester’s English started to sell Pennyroyal Pills for profit. Women no longer received the herb from women in the neighborhood who knew what they were doing. Instead they bought the pills for only $2 in a drugstore. Chichester’s English also advertised heavily in local newspapers and with posters. They also mailed pills to women via post. The herb moved from the community sphere to the public economic domain.

Knowledge about herbal medicine used to be passed on from generation to generation. Especially information about contraception and abortion since this was not yet part of recognized medical spaces, such as hospitals. Nowhere on the Pennyroll Pill box is an explicit explanation of what the pill is supposed to do, so Chichester’s English relies on previous information already known to women. Kate McDonald explains that this information is “to be understood by those who knew what to look for, but without attracting legal attention.” The most explicit mention on the poster is “restore and regulate menstrual function”, which still remains vague, although it is an obvious hint to its function to end pregnancies and start the menstrual cycle again.

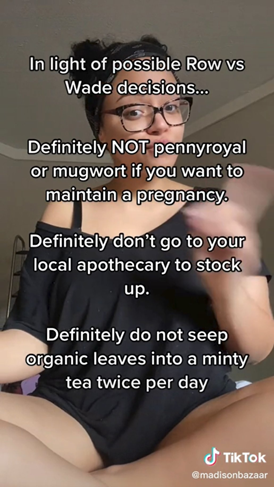

On June 24th, 2022, the right to abortion was overturned in the U.S.A.. Our society looks very different now, more than a 100 years after the popularity of pills with pennyroyal. In 2022, we also use social media to gather information. Even before June 24th, young women started to share information on TikTok about herbal abortions, including the use of pennyroyal. Mary Jane Minkin, MD, a gynecologist and clinical professor at the Yale University School of Medicine says “I’m horrified. They’re going to kill people. Forty-nine years ago, that’s how women died.” Claudia tells me that “the fact that these poisonous and therefore dangerous substances are spreading again today is more than worrying. However, it shows the desperation of these women to end an unwanted pregnancy despite strict prohibitions”.

I’m horrified. They’re going to kill people. Forty-nine years ago, that’s how women died.

Mary Jane Minkin, gynecologist and clinical professor.

Women have always shared information about contraception and abortion with each other, historically within communities and currently also on social media. Sharing has become easier with social media, but medical professionals express a fear for misinformation. Claudia mentions that “another problem is that today’s possibilities of social media make it possible for this half-knowledge, which is sometimes dangerous, to spread quickly.” Luckily, there are also other TikTok users who respond to the recommendations of pennyroyal by explaining how dangerous it can be. While women’s bodies continue to be policed, it is vital to share knowledge. However, it is equally important to promote safe options for abortion.

Many thanks to Claudia Grammer and Diana Riegler from the Museum of Contraception and Abortion, Vienna for their collaboration!