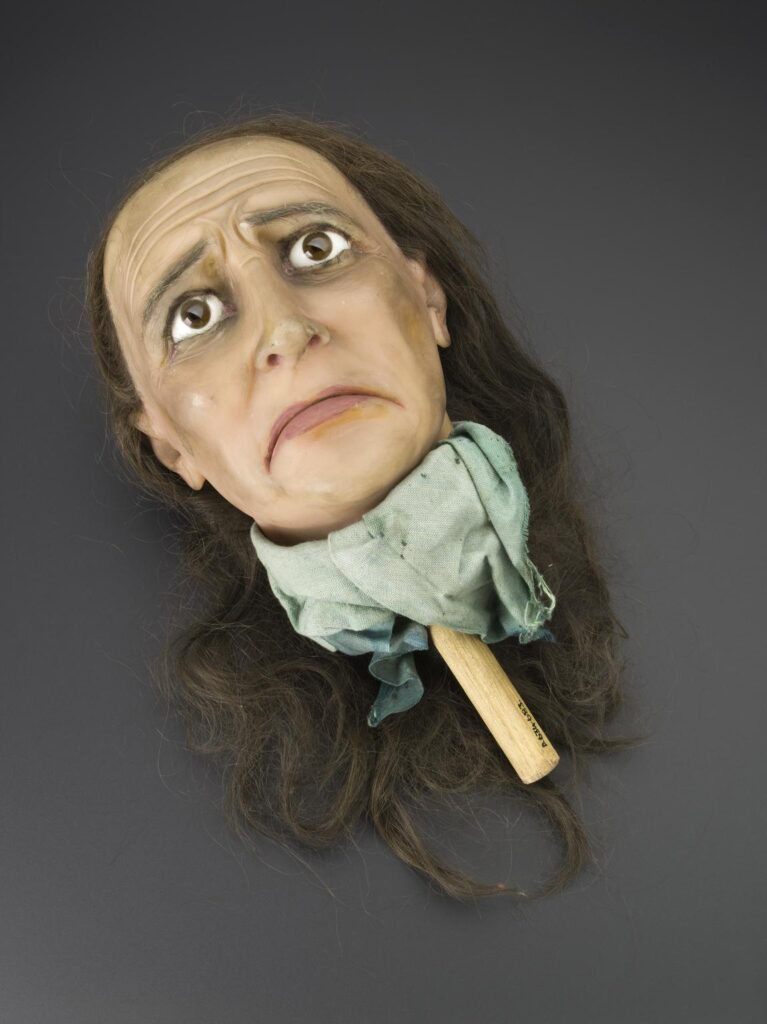

Her forehead frowned, her eyes big and bulging, pouted lips and her hair black and stringy. She looks unkempt, worried, almost scared and wears a blue scarf around her neck. By looking at her face, inspecting every inch of it, you start to wonder whether she is doing alright; she looks panicked. You start to feel compassion towards her. However, in the 1930s they felt anything but empathy for this woman. They would stay far, far, away from her and would even lock her up. According to Henry Wellcome’s Historical Medical Museum, this was what madness looked like. This was a madwoman.

The Wellcome Historical Museum exhibited life-size wax models of men and women ‘gone mad’, tied up with replicas of restraints used in asylums in the 19th century. The madwoman described above literally lost her head, which is now saved in the collection of the Science Museum in London. Even though the maker of the wax figure is unknown, as well as the whereabouts of her body, her head tells us the ongoing history of the madwoman.

Life size wax head of a melancholy insane woman, English, 1910-1950. Overhead view of whole object against graduated grey background.

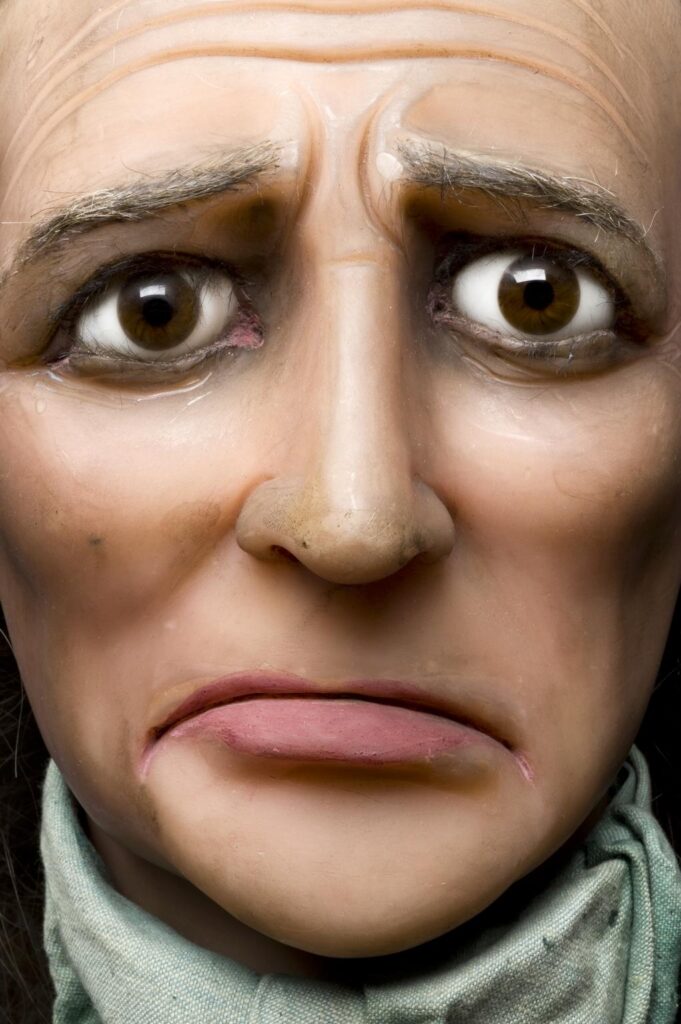

Life size wax head of a melancholy insane woman, English, 1910-1950. Detail view, close in on face.

Life size wax head of a melancholy insane woman, English, 1910-1950. Full profile shot, back lit on hair. Graduated matt black perspex background.

The ‘Madwoman’ falls within the long tradition of women’s oppression, but also women’s emancipation. The nineteenth-century saw a high increase in the number of intakes in psychiatric institutions. It was mainly women who were admitted; they were given the title madwoman. The difference in the number of incarcerations can be explained by the ignorance about the effects of the menstrual cycle on women, the disparity of rights between genders and the dissimilarities in social expectations. First and foremost it was thought that women were more vulnerable to insanity because of their reproductive system. Besides this misconception, nineteenth-century society was male-dominated. Men held prominent positions at work and were the man of the house. In The Writing Madwoman: Challenges for 19th Century Women Writers, Jessica Schlepphege argues that possible triggers for madness in women were “the lack of meaningful work, hope, or companionship.” In a century in which women were expected to take care of the household, these are not strange sounds. When a woman behaved differently than the social norm – for example, she did not want to marry, would not take care of her children or masturbate – she was considered crazy. It was (surprise, surprise) men who made this diagnosis since women were not allowed to work in asylums according to English law until 1927.

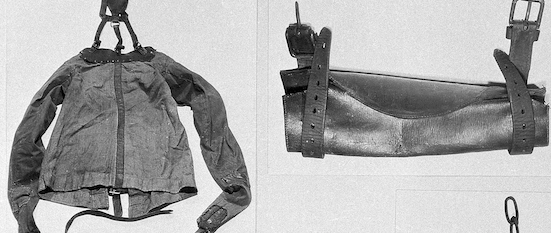

Diagnoses by psychiatrists at that time were a lot different than nowadays. Specialists in the field today have more knowledge and tools to determine (somewhat) specifically which mental health issues you suffer from, as there are many different types of illnesses and disorders. Back then, psychiatrists saw no difference in mental illness, physical illness with mental consequences and disorders in behaviour, as Janet M. Torpy states. You would simply get the label insane. Once they diagnosed a woman mad, she would be put away in an asylum. As shown on the wax models in the Wellcome Historical Medical Museum, the people in incarceration were shackled with restraints. The museum sought to cover the history of medicine from prehistoric times to the present day. When she was still intact, the wax doll was probably used to show off the restrain methods used in asylums. In the collection of the Science Museum London, several of these restraints like straitjackets, blankets, harnesses, wrist restraints, and more are also included. Most of the ones they own were used throughout the 1930s, until the 1960s.

Not only unstable women were at risk of being put away. There were many independent females, who intimidated males to such an extent, that they were detained in psychological institutes. It was often their own husbands to whom they owed their incarceration. These men acted out of fear for the smearing of their reputations. Some brave women who were victimised by their husbands refused to be shut up and wrote down their experiences. In her research, Savannah Jane Bachman explores how madwomen are portrayed in Victorian Literature. Her work is valuable because she shows how the concept of the madwoman led to oppression, but most of all emancipation of women in the 19th and 20th centuries. Non-fiction as well as a lot of fictional stories about madwomen flourished in Victorian England. Historical accounts, like the story of Louisa Lowe, The Bastilles of Engeland (1893), were mostly about women who were falsely accused by their husbands and diagnosed by male psychiatrists as being madwomen. The stories they wrote were testimonies about the injustice that was inflicted on them, hoping to raise awareness. In Victorian novels too, the lives of madwomen were described. Often the stories would be about women who were driven to lunacy by their husbands or families, resulting in their captivity. It is debated whether these novels stigmatized madwomen and were used by psychiatrists as examples of why madwomen should be brought into an asylum. The visitors of the Wellcome Historical Medicine Museum would recognize the exhibited wax models directly as insane women, resulting from the existing stereotypes. However, according to Bachman, both non-fictional, as well as fictional stories about madwomen brought serious attention to women in asylums, influenced the public perceptions of female madness and led eventually to changes in the English lunacy laws.

“And there’s nothin’ like a mad woman

What a shame she went mad

No one likes a mad woman

You made her like that.”

Taylor Swift

To go back to the wax head, pictured above, in the collection of the Science Museum in London. It would be kind to offer this woman a name since she resembles so many women in the Victorian era, as well as women today. This comes back to the quotation above. You might wonder why I chose part of the lyrics of a Taylor Swift song. Released in 2020, the song Madwoman, a reaction from Swift to injustices that she and other women are challenged with on a daily basis, is similar to the stories about madwomen in Victorian Literature. This shows that the wax head, that we from now on call Madison, and the story she tells, could be part of a powerful exhibition about women’s emancipation.

Janneke Gemmeken