Upon entering Pieve Santo Stefano, a tiny tucked-away village in Arezzo, one encounters Italy at its quietest. Seeing no one on the streets but a few people in front of a tiny bar and an old couple walking their dog, nothing here seems particularly tumultuous or emotionally intricate. If only visitors knew they had entered the very heart of Italy’s documented inner lives; that right there, underneath their feet, was stored the greatest collection of diaries from all of Italy. The small diary museum, located in the heart of this village, houses the intimate result of a widow relieving her grief: Clelia Marchi’s inscribed weddingsheet.

This sheet belonged to Clelia Marchi (1912-2006). Right until the moment she started to write on the sheet, Clelia had lived her whole life in Poggio Rusco, a small town near Mantua, working as a farmer alongside her husband Anteo. They ran a small farm, producing mostly corn; it is in that small house, among some four fields of corn, that this sheet has come into being. It did so in dark times: after a fifty-years marriage, Anteo dies in a car accident, leaving Clelia behind. Clelia is overcome by grief after her husband’s death. Years pass by shrouded in grey; as Clelia describes, she was mourn-struck and increasingly came to feel depressed and isolated.

After her husband’s passing, Clelia writes she felt like “una vite senza l’albero”, a vine without a tree.

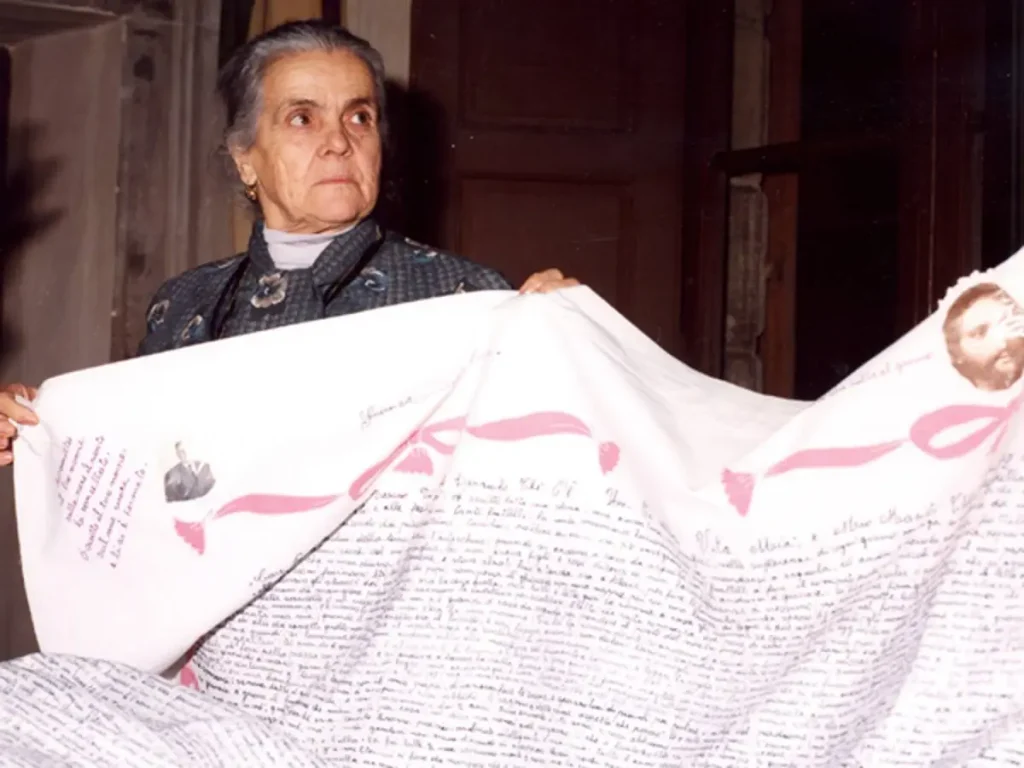

Clelia Marchi on her sheet

Clelia could not, these first years, think of any means to enlighten her sadness. The life of her and her husband had been entirely shaped by the work on the land, and accordingly, by the passing of the seasons. Neither of them had had any education beyond primary school, yet they had excelled in cultivating their land, always side by side. How to carry on alone? How could she relate to this unfamiliar darkness, how could she make it disappear? All this time, Clelia still inhabited the farmhouse she used to share with Anteo. She was, therefore, still surrounded by the objects they used to work with together, and these artefacts of her previous life would come to play a significant role in what would become her way of relieving her grief.

Relieving the pain

After some years, Clelia decides that this state of being can no longer go on. She comes to think that, maybe, if she writes down everything her husband and she have been through – thus safeguarding the memory of their shared life – she will then be able to leave it behind. Not having any paper, however, Clelia is forced to think of some other way to document her thoughts.

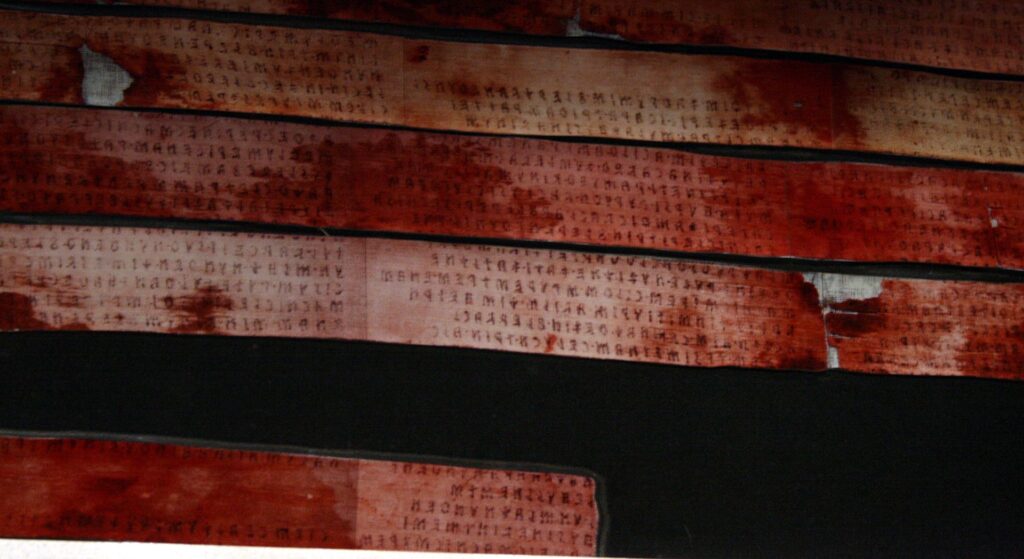

She then remembers how Angiolina Martini, her teacher in primary school, told her that there had once been found a mummy that was wrapped in cloth inscribed with an Etruscan text! Clelia begins to search for an object that has been central to her marriage, a piece of cloth that has witnessed each day of their shared rising and falling asleep, but which has been locked away since her husband’s decease: their weddingsheet. For two years, Clelia would return to the sheet during sleepless nights and write down the memory of her life with her husband Anteo in as much detail as she can.

The importance of objects

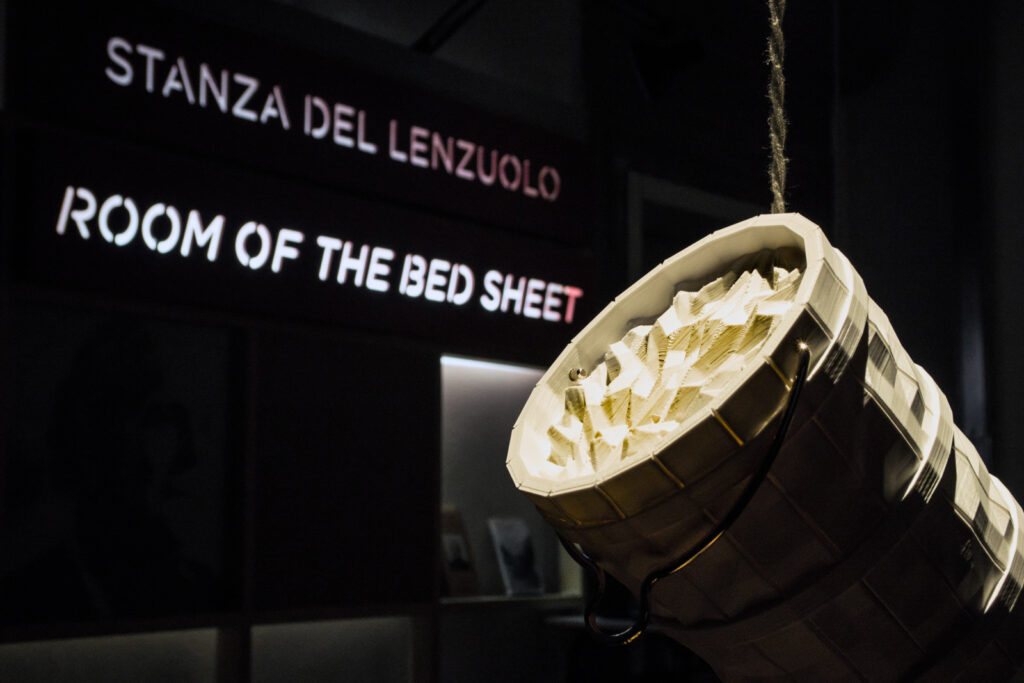

Remarkable about Clelia’s writing on the sheet, is the central role she attributes to the objects in her life. Rather than turning inwards and performing a psychological self-exploration, Clelia recalls the material reality of life of hard agricultural work. It is the bucket she and Anteo used to transport corn with, the rod with which she swept their house and the mill grinding their coffeebeans each morning, that feature among the most prominent actors in Clelia’s lifestory. The museum has accordingly hung 3d-printed versions of the objects described in Clelia’s story in front of the sheet. Upon approaching the objects, they will begin to softly whisper excerpts from Clelia’s sheet; pieces of texts about how Clelia related to the object and what they have come to denote for her, having accompanied her and her husband for decades.

Besides the practicality of a lack of paper when Clelia wished to write, her using of an object that was strongly connected with her married life can also be seen as a rite de passage. By writing upon this sheet, Clelia acknowledges that it will never again be used for its original purpose: to keep warm and hold together two lovers. two She transforms the object from a marital utility into an artefact of married life, which is underscored by the fact that the sheet now no longer resides in Clelia’s and Anteo’s home, but in the public space of a museum. Before Clelia started to write on the sheet, it was undecorated – it did not contain any specific reference to her marriage, but it being a large, beautifully knit sheet, Clelia and Anteo had slept in it for years. After Anteo’s death, it was this sheet that Clelia chose no longer to sleep to in. To Clelia, the sheet was thus already a precious relic to her marriage, even before the outside world would be able te recognize it as such. Upon her passing the written-on version on to the museum however, she decides to explicate its relation to her marriage by embroidering it with garlands and two little portraits of her and Anteo. Clelia anticipates her sheet being seen by a public and thus transforms it into something that can be understood as meaningful and intimate not only to her, but to a larger public unfamiliar with her life.

Preserving lives easily lost

It was Clelia herself who decided to show her sheet to the public. In 1985 she presents her sheet to the mayor of Poggio Rusco. He is impressed and tells Clelia about the diary archive in Pieve Santo Stefano. There Clelia’s sheet is warmly received and gently taken care of, up until this very day. Besides its aesthetic beauty, Clelia’s sheet also conveys a testament of lives so easily lost to time: the loves and fears, thoughts and expectations, and the daily doings of peasants in the middle of the twentieth century.

By Loulou Kokkedee