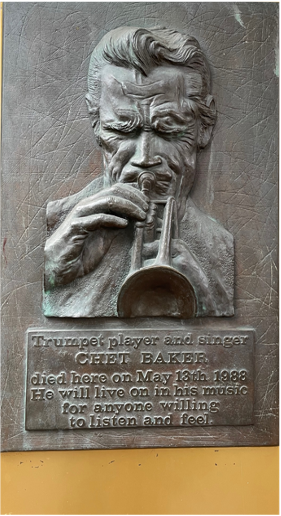

On the 13th of May 1988, the “Prince of Cool”, commonly known as American jazz artist Chesney (Chet) Baker, was found dead. Fallen from the window of his second-floor hotel room in the Prins Hendrik Hotel in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. The then 58-year-old’s bloodstream revealed traces of heroin and cocaine. To commemorate the musical innovator, a plaque was revealed on the front of the hotel in 1999. The caption reads: “Trumpet player and singer Chet Baker died here on May 13th, 1988. He will live on in his music, for anyone willing to listen and feel.”

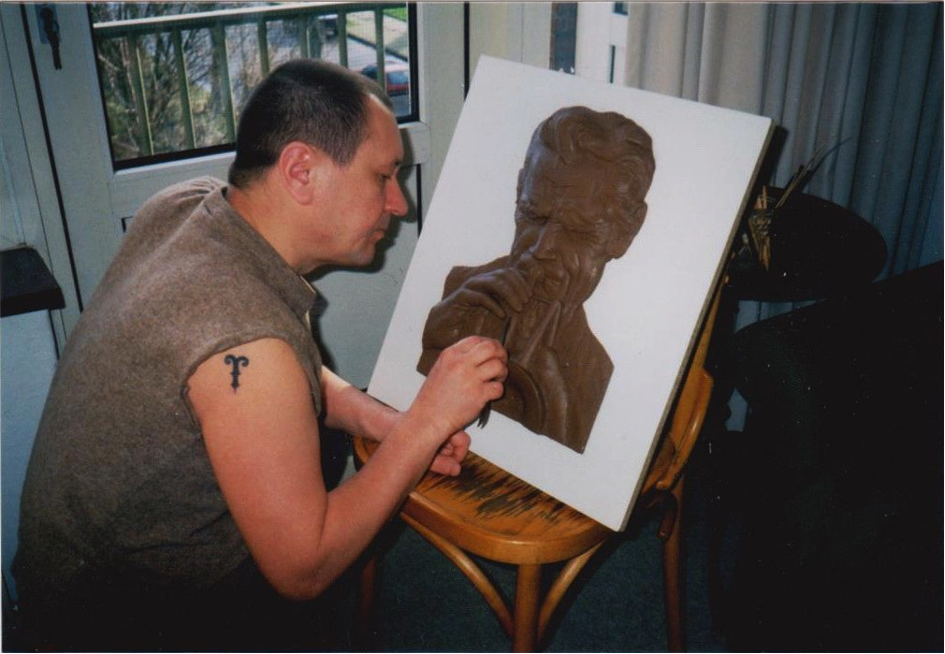

The main contributor to realizing this memorial was Chet Baker-fanatic Bob Hagen, chairman and driving force behind the jazz foundation “Stichting Jazz Impuls”. Together with the Amsterdam-based artist Roman Zhuk, a bronze plaque was produced. It showed a relief of Chet Baker from the late 1970s, when he was in his European period. His best musical period, according to the initiators. Since the plaque was financed through donations from enthusiasts, it was crucial to show Baker in a way where he was recognizable. Not just by getting the face right, but also by the expression, his way of playing, and the words that adorned him. Hagen wanted people to walk by and think: “That’s how he was”. The words under his relief are cited from an interview Baker gave. It took over a year to get it right: changing his hair, moving his trumpet to his lips, and showing the passion for music on his face, as “He didn’t live for the fun of life, he just cared about using and playing.”

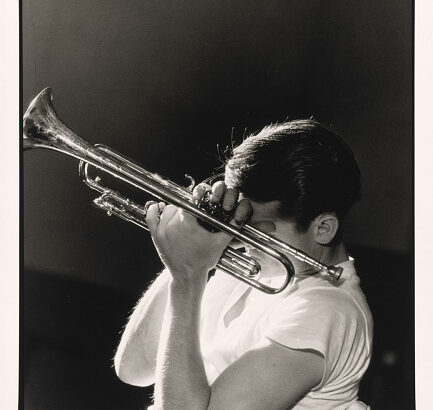

How is Chet Baker remembered through this plaque? His relief on the plaque shows a man who could either be very passionate about his playing, simply in pain or both. Baker, as an artist, was commonly described to be either singing or singing through his trumpet. He had a soft, thin way of playing, and every note was planned and provided. As a frontman, responsible for improvisation during shows, concentration and passion are crucial. This all comes together in the relief, which is exemplary for his career. After playing in Charlie Parker’s (nickname: Bird) band for a little while, he met Gerry Mulligan in 1952. Their relationship is another example of how passion for music triumphs all. Their personalities contrasted but finding each other in their playing was like a chemical reaction. From there, Baker went on to make around 200 records with different artists by his side, never losing his musical persona. Turbulence in his life, however, did influence his career both musically and mentally. Still, one can always recognize Baker’s signature sound.

This memorial is not the first attempt at publicly commemorating Baker’s passing. Before this plaque was introduced, it was preceded by a different statue a year before in 1997. An anonymous admirer, which we now know to be the same fanatic Bob Hagen, illegally placed a statue with an old trumpet and a laurel wreath. At the time, this was deemed a bridge too far by the municipality as they were hesitant about “remembering a junkie”, and the statue was taken down. With the arrival of a new alderman the following year, who coincidentally also turned out to be a Baker-fanatic, the current memorial was approved and built in 1999.

Controversy around Baker’s drug abuse throughout his career and at the time of his death changed over the course of a year, as people understood this memorial was intended to stress his influence in music rather than other influences from his life. Baker had come into contact with drugs early in his career through Gerry Mulligan, but in his own words had stayed: “As clean as a whistle. Bird told me to stay away from drugs. I was 22 at the time and didn’t start taking drugs until I was 27.” A few years later, during his first European tour, Baker found one of his band members dead after an overdose, which totally destroyed him. When he returned to the United States, he mentions that he purposely started using heroin. A combination of guilt about the death of his band member and curiosity drove him, stating: “I had to find out about it.” Throughout his career he was incarcerated many times all over the world, recovered from using, and started again. This went hand in hand with his career, since after he was badly beaten up in 1968 by junkies, he put a temporary stop to it. Baker’s image during his lifetime, then, was heavily influenced by his struggle with drug abuse. However, after his death, it seems his music remains the most vital part of his image.

For people, and artists, creativity has its boundaries. Nowadays, artists are heavily advocating for the right to protect their own mental health by, for instance, canceling their performances. The notion of the Tortured Artist is heavily debated. While art is certainly a reflection of humanity and humanity’s greatest virtue can be seen to be its ability to overcome adversity, pain should not be seen as a requirement for the creation of great art. Baker, then, could be seen as a primary example that through all the adversity, he never lost his touch and one could always recognize “The Prince of Cool”. When he starts playing, the question of whether Baker was “Born to be Blue” or a Tortured Artist, seems insignificant.

This is “Everything Happens To Me”, for anyone willing to listen and feel:

“I never miss a thing, I’ve had the measles and the mumps.

And when I play an ace, my partner always trumps.

I guess I’m just a fool, who never looks before he jumps.

Everything happens to me.”

Chet Baker

Niels Nordholt