‘Can the Tropenmuseum ever really be decolonized, being a former colonial institute?’, asks Mitchell Esajas himself in his reflection about the exhibition ‘Afterlives of Slavery’ – a semi permanent exhibition that opened in 2017 and is currently still open in the Tropenmuseum till the end of 2020. In the fall of 2017 25.000 people visited the exhibition – per month.

The exhibition, which is very small, has a clear aim: to inform people about ‘our shared slavery past’ and how we can use that information to investigate how people nowadays look at this topic and, maybe the most important question of the entire exhibition: ‘how can we create a shared future?’. The underlining reason is that in the present day a lot of people still don’t see the connection between that slavery past and nowadays racism, discrimination and inequality.

This underlying reason is clearly visible in the exhibition. Besides the factual past, which is categorized in different subjects with their own colors, there is a link to the present. A good example is the subject ‘protests against racism’, in which not only protests from the 1970s are presented but also the protests against blackface and the protest against the figure of Black Pete. It is a very current exhibition, that makes the visitor think. It asks questions in which the visitor really has to think about its own values and norms. Because of the questions, the exhibition really gets people to think about how they look at ‘our shared slavery past’.

But the questions and information also have a different side. While visiting some of the rooms, I couldn’t help but feel guilty to have been born in a country that used to trade in enslaved people and that has, up till now, issues with that difficult past. When the question is raised if the apologies and the increasing sharing of knowledge are enough, I can’t shake off the idea that it is never going to be the case. This sense of guilt is what the conservator Stijn Schoonderwoerd didn’t want: ‘we don’t want people to think: ‘oh this is too heavy, I’m going to skip that room. Guilt and penitence. It has to be an inviting exhibition’. While the colors and the objects in the exhibition are very welcoming, the text is quite the opposite at certain points.

This could be traced back to the partnerships. The Tropenmuseum wanted to be careful about their language and image shaping, so they asked academic including Gloria Wekker (White innocence, 2017) and activists, for example Hodan Warsame from #decolinzethemuseum. The goal of this activist group is ‘to confront the colonial ideas and practices present in ethnographic museums up until this day’. Their partnership is visible in the explanation texts. Whereas maybe ten years ago, the text would have said ‘slaves’, now it says: ‘enslaved’. This partnership has thus brought some positive elements, but you could also say that the activists voice sometimes is too loud when it comes to blaming people, even though Schoonderwoerd says the museum is in charge of the final product: ‘we don’t want to be the toy of a group’.

A different element I mentioned before, is the size of this exhibition. For such a relevant and hot topic, the size is extremely small. Although a lot is explained and shown, it feels like the Tropenmuseum felt they had to do an exhibition about slavery and how this still is felt in the present. For a museum that has a past of a colonial institute, as said before by Esajas, it feels too small. Especially since the museum is so focused on his own history. When you walk into the museum there is a hall in which the frequently asked questions are placed, all of them regarding colonialism. It made me feel like the museum felt they had to do something with the subject, so it was addressed and the audience was pleased that the museum had spoken out about this subject. As it turns out, this exhibition is just the beginning: the museum is now working on a permanent exhibition about colonialism and slavery.

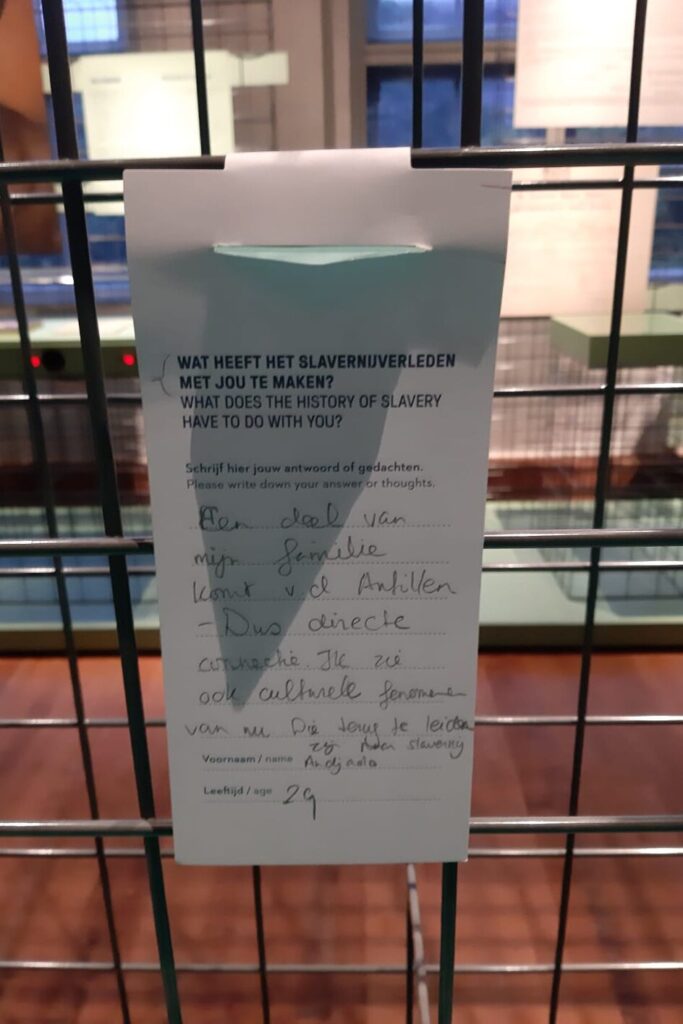

This new exhibition, called The Heritage, is being developed and is planned to be open in 2022. The Tropenmuseum wants to have as many people involved in the creation as possible. At multiple places you can write your opinion, you can email the museum or contact them on social media. These opinions range from very positive to people who thinks the racism topic is exaggerated. In the museum there are a quite a view questions asked on notes and a lot of people have taken the time to answer these questions and write down their answers. One person answers to the question ‘what does the history of slavery have to do with you’:

‘A part of my family is from the Antilles, so there is a direct connection. I also see cultural phenomenon from the present that have their origin in slavery’.

This interactive part, in which the public feels very connected to the museum and in which they feel important, is something I would advocate strongly for. People feel like they have a voice and they (and their past) are relevant to the big story, which is something I would like to achieve if I was a conservator or staff member.

The exhibition The Afterlives of slavery has created an open space, where people can think about their past, present and future and how that is related to slavery. It is a place where people can give their opinion and feel heard at the same time – a very impressive result for such a small exhibition. You can definitely feel that this is just the beginning: something bigger is coming our way about slavery and colonialism. And I am excited to see what the results will be.

Mickie Rijnsburger