This summer, I was on a holiday in the South of France. The eating of snails has always had a high place on my bucket list, and this summer I tried them for the first time. One time in Aix-en-Provence, and one time in Nuits-Saint-Georges. Both times incredible. The garlicky, buttery, parsley liquid was magnifique.

Although we associate cochleas, or better known as snails, with French cuisine nowadays, their culinary roots stretch back to ancient times. It may come as a surprise, but the eating of snails is almost as old as time. In modern-day Spain, the Homo sapiens started eating snails over 30,000 years ago. Other prehistoric Mediterranean cultures adapted the same food culture when it comes to snails. It was during this period that the Homo sapiens diversified their diet in order to increase the population and to better their health. Recent research on this subject suggests that the prehistoric humans picked the snails carefully. Something that is perhaps better known, or at least slightly better, is the snail-eating culture in the Roman Empire. This blog post focuses on the eating of cochleas in the Roman Empire and the question whether snail consumption culture reflects elitism and social hierarchy or not.

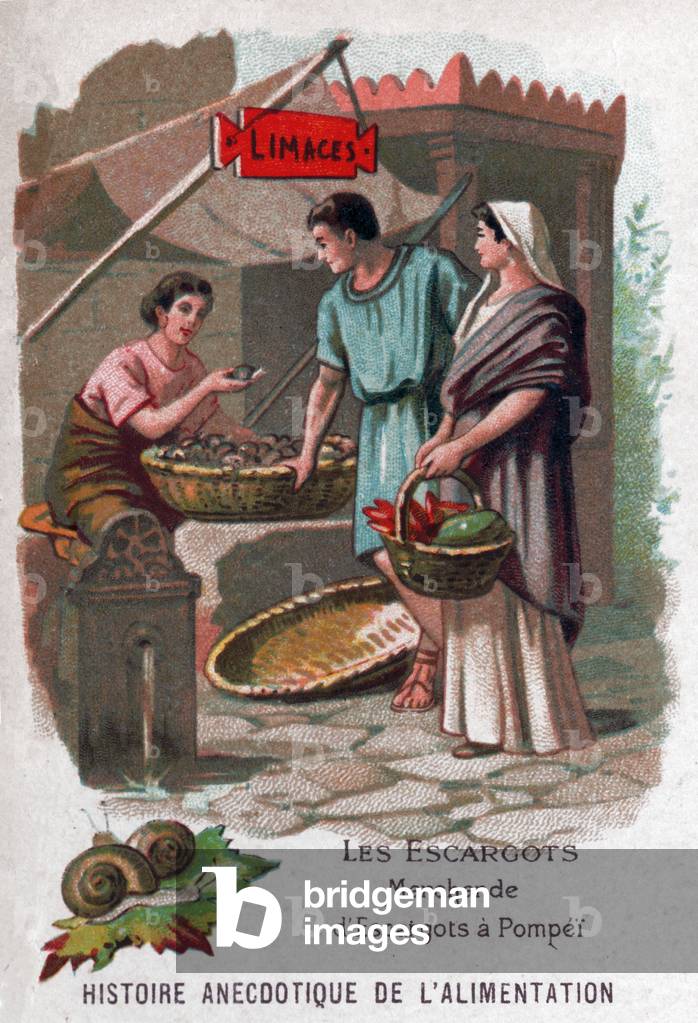

Heliciculture and snail-trading

So, snail-eating was already widely spread in the Mediterranean when the Roman Empire emerged. In 49 BC Fulvius Lippinus described how snails ought to be harvested – the explanation of heliciculture (snail farming) was sufficient to make an appearance in Naturalis Historia by Plinius the Elder. Being the first documented snail farmer, his farms were considered innovative because of his use of state-of-the-art irrigation. In his cochlearia, Fulvius Lippinus had several designated areas for different breeds of snails. Some species were European, but he was best known for his imported African snails, which could easily reproduce. It definitely was a day-to-day practice for Fulvius Lippinus: he picked the species personally and carefully, which resulted in a rise in the pricing of the snails.

To demonstrate the time and energy Fulvius Lippinus had to invest in the heliciculture, presented here are ingredients or spices he fed the snails. He assembled his own formula to feed the snails. This formula consisted of wine yeast, flour, and spices. The belief was that the snails would become fatter, which was useful for the sales and consumption. The snails could reproduce quicker and better – which then resulted in a larger quantity for selling. Another method to flavor up the snails was making use of a honey-based liquid called sapa. Mixed with flour, the snails would also fatten and be ready for consumption. Fulvius Lippinus ended with a large company that stretched way further than just the Mediterranean Sea. Remains of Roman snail-eating have been found in (among others) nowadays Morocco and Albania. Plinius the Elder explains in his book that Fulvius Lippinus made a ferry service for the import of the African snails, which exhibits the large scale he worked on.

Snail-eating culture and elitism

The Roman Empire was inherently an elitist society, with a wealthy high class and poor middle and low classes. Whether snail-eating was an elitist hobby, or a poor-man’s business remains unclear for now: almost every academic source argues that the consumption of snails was strictly elitist, but I wonder if that is correct. The snail-eating itself was merely done in-house. The Roman elite adored snails fattened with milk that were served on a flat plate with milk and salt.

It is true that Fulvius Lippinus’ company was solely based on the market of the elite. There has been found proof of the presence of snails in Roman feasts or banquets, which were generally for the Roman upper class. Though that does not mean that the other Romans lacked access to the consumption of snails. Some academic sources suggest that the middle and the lower classes did eat snails, but that they harvested them from their own garden. They just did not have access to a large company that farmed and cultivated the snails for them. That resulted in the elite having the better, fatter and more tasteful snails, and the other classes just ordinary snails. Although the inequality that ruled in the Roman Empire thus also manifests itself in the snail consumption, the Romans were the first to really incorporate the consumption of snails in their culture. Many people nowadays believe that that is where the eating of snails generally commenced, but as we have discovered before, that is incorrect. Due to the rise and fall of the Roman Empire though, the popularity of snail-eating spread swiftly through Europe.

In sum, it has become clear that Fulvius Lippinus was the first major producer of snails in his vast snail farms. His snails were solely harvested for the elite, while the other classes cultivated the snails from their own gardens or from the wild. Although this illustrates the inequality within the Roman Empire, the ancient times did establish a never-ending popularity for snail consumption in the western world. Concluding, it has become notable that the food industry, or at least the snail industry, in Roman times reflects social hierarchy.

For further reading:

- Holleran, Claire, A Handbook to Shopping in Ancient Rome. Oxford: Oxford University Press (2012).

- Apicius, Cookery and Dinery in Imperial Rome. New York: Dover Publications Inc. (1977)

Written by Max de Bakker