In October 2017 the Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam opened a small exhibition about the Dutch history of slavery. The exhibition is not just about the past though. “Afterlives of Slavery” connects the history of slavery with the present. After all, the colonial history doesn’t end with the abolition of slavery. Up until today people face racism and discrimination. These present-day issues are in a way a consequence of the Early Modern racial structures. According to an article published in the NRC Handelsblad, the aim of the exhibition is therefore to give context to today’s debate about racism.

The introduction to the exhibition lists questions as “What is our shared history of slavery?” “How do we deal with it today?” and “How can we create a shared future?” These questions obviously address to the aim of the museum to be a “unifying force,” as the director of the Tropenmuseum, Stijn Schoonderwoerd, states in an interview. “We see it as our duty to inspire people to world citizenship. This is really necessary in times of xenophobia.” The ambitions are high. This exhibition is therefore just a prelude to the real thing. In 2021 the Tropenmuseum aims to open a bigger permanent exhibition on the history of Dutch slavery.

A different point of view

This smaller exhibition is only showing one point of view, as the director explains. They chose the viewpoint of the current Afro-Dutch generation. Therefore, the museum cooperated with different people and organisations, by way of a focus group. #DecolonizeTheMuseum is one of them. This action group strives for de recognition of the Dutch history of slavery, the end of institutional racism and the decolonization of people’s minds. Their ultimate goal is a world free from thinking in colonial structures.In her article about the decolonial dynamics in the Netherlands Sharilyn Deen states that groups like this contribute to make questions about the Dutch colonial past and racism a public issue, rather than just an issue of descendants of former slaves.[1]

For me, the collaboration with the current Afro-Dutch generation is most clearly visible in the spoken word performances of Dorothy Blokland and Onias Landveld. Their performances were recorded in the Tropenmuseum itself and displayed on big screens in the exhibition. They look right at you when saying “this is your history too!” I saw visitors sitting in front of the screen in silence and some of them clearly needed a moment to allow this to sink in. I was also moved by the performance, I felt personally addressed and somehow started to feel guilty about the past.

Even though conservator Martin Berger clearly states in an interview with “De Telegraaf” that no one should feel guilty about this past, I think some people do. This also becomes clear in the notes people leave behind in the exhibition. A boy wrote down “we should learn more in school about these wrong things we were doing.” In her article Deen also writes about this complicated victim-guilt-question. In the exhibition although this issue is not (yet) present.

A space for debate

In my opinion the exhibition succeeds very well in creating a space for debate about slavery and racism. Instead of a chronological overview of the history of slavery, the museums chose to work with different topics. While the topics about “creativity and resistance” and “freedom” focus on the past itself, the topics “creation of race” and “the future of the history of slavery” have a more direct link with the present. The section about the “creation of race,” for example, has a display with objects related to the zwarte pieten-debate. This makes the history of slavery all of sudden very relevant today for, I think, almost all (Dutch) visitors. The part about “the future of the history of slavery” is very obvious related to the present. And yet again the exhibition makes it even more personal by displaying a list of names of formal slaves where you can look for your own name. I found mine, and without realizing I somehow participated in the slavery debate by posting a picture of it in our family WhatsApp.

But even in the first two topics, visitors are invited to think rather than just absorb information. In each section an expert gives information and their messages always end with a question. “Do you really want to know where you came from and what would it change?” “Who or what determines the limit to your freedom?” Questions as these definitely make it easier for visitors to feel related to the subject. Together with objects and stories, they narrow down the distance between the former enslaved people, their descendants and visitors of all kinds. During my visit I saw people talking about the questions and the objects, a sign that the museum succeeded in its aim to make these issues part of the public debate.

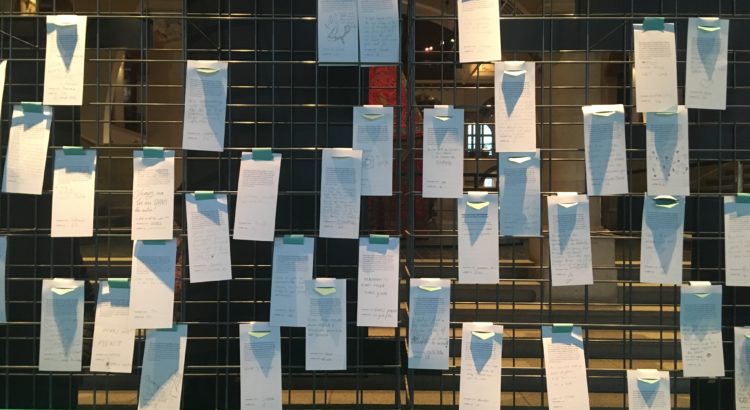

Besides these debates created by the way things are displayed and contextualized, the center of the exhibition is especially designed to participate as a visitor. Here you have the option to share your opinion on social media, email the museum or just to write something down, a suggestion or simply something you wanted to share with others. And it works, the walls are full with notes. This is a very nice example of how museums can cooperate with their visitors.

“Afterlives of Slavery” is the beginning of a change in how we handle the history of slavery. For now, only one viewpoint is shown, the one of the current Afro-Dutch generation. As a result, the museum is not yet the very unifying factor they aim to be, since I still feel like it’s us and them. Besides that, the exhibition definitely succeeds in her contribution to the debate about racism and in creating a space for debate and therefore definitely worth a visit. I hope there will be other viewpoints on display in the new exhibition of 2021. But that will be the case, if they consider my little note, next to all the other hope giving, positive, loving, critical and grateful notes.

Laure Lambert

[1]Sharilyn Deen, Tracing pasts and colonial numbness: decolonial dynamics in the Netherlands, Etnofoor 30, nr. 2 (2018): 11-28.