Between 1938 and 1968 around 400 sex offenders underwent therapeutic castration as part of their treatment after being put at the discretion of government. Even though this procedure was only performed on a voluntary basis, statistics show that mostly people with a weak social position, mentally handicapped people and homosexual men, were castrated. This raises questions about how voluntary this surgery really was and to what extent it was influenced by prejudice about homosexuality.

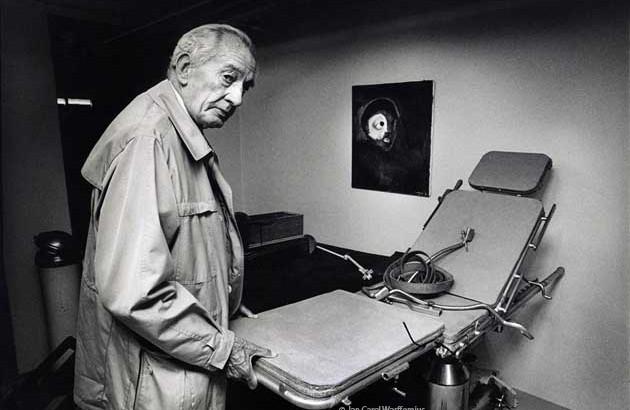

This controversial history did not stay hidden in the ivory tower of historians and psychiatrists, but was also taken up in emotionally charged public debates. Today, we can hardly imagine that surgical castration could be the medical solution to sex offenders. The role of article 248bis and homosexuality in this history led to fierce discussions. The picture of dr. Wijffels near his surgical table illustrates two sides of this debate: one image of a horrible history filled with victims and villains, another of an out-dated medical treatment.

The adult who fornicates with a minor of the same sex whose minority he knows or should reasonably suspect, shall be punished with imprisonment not exceeding four years

art. 248bis., Dutch Code of Criminal Law

In 1911, driven by a sense of decay of morals in Dutch society, new laws were enforced to protect minors. One of these articles caused controversy, because it criminalised a certain group of people: homosexual men and women. Article 248bis convicted adults who had a sexual encounter with minors of the same sex between the age of 16 and 21. However, most sex offenders were convicted under art. 247 which forbade sexual contact with minors under 16 or art. 239 exhibitionism.

A conviction as a sex offender could lead to being put under the discretion of government [Ter Beschikking van de Regering, TBR]. TBR-patients were confined in an asylum for a maximum of four years, but this sentence could be renewed. In practice, this could mean lifelong captivity. Castration provided the opportunity for a faster return to society. 384 sex offenders, which is only a small percentage of the total TBR-patients, ‘chose’ this option. Most of them were prosecuted for having sex with minors under 16. 5% of them, which is less than 20 people, were convicted under article 248bis, for a sexual encounter with minors of the same sex between the age of 16 and 21.

However, homosexuality did play a remarkable role in this history. In the twentieth century, homosexuality was still considered to be a deviation of normal (hetero)sexuality and therefore as a mental disease. Furthermore, homosexuality was mostly ranged under the term ‘hypersexuality’. Within the sample of people castrated, homosexual men made up about 40% of the group. This is remarkable, considering the division of hetero- and homosexuality in society in general. Apparently, same sex offences with boys were regarded worse than offences with girls.

Transl.: What do I care. Better unhealed in liberty than unhealed in an asylum

Leo, homosexual man castrated in 1938, in: M. Sluyser, Niemand die het antwoord weet (1967) 97.

Castration was not simply or randomly executed or even a punishment: there was a strict procedure for the application and implementation of castration of TBR-patients formulated by the Ministry of Justice in March 1938. The voluntarism of the patient was crucial in this treatment. A letter by the patient was sent to the minister of Justice, who held the highest and final responsibility: only with his approval, the castration could take place. The surgery intended to extinguish their sexual urges, but some homosexual men believed that it would cure them from their sexuality.

Transl.: Everything that would go with that surgery, too much to remember, let alone understand.

Leo, homosexual man castrated in 1938 in: M. Sluyser, Niemand die het antwoord weet (1967) 102.

Even though patients had to be well informed about the nature and all the consequences of the surgery, this quote shows that this was not always the case. For example, there was a man who even believed that his penis would be removed. Moreover, most of the patients had a vulnerable social position, due to their homosexuality or their mental handicap. Patients also had to deal with fear of exclusion in society, moral judgements and social and psychological pressures. The voluntarism can therefore be doubted and many patients saw castration as a sacrifice for their freedom.

Controversy in interpretation

![Brochure ‘Bewaar mij voor de waanzin van het recht’, 100 jaar strafrecht en homoseksualiteit in Nederland [‘Save me from the madness of the law’, 100 years criminal law and homosexuality in the Netherlands] published by Ihlia in addition to the exhibit. Photo courtesy of Maddie van Leenders](https://publichistory.humanities.uva.nl/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/FotoBrochureDicht.jpg)

With these peculiarities in mind, we turn to the controversial afterlife of this history. Considering the doubtful procedure, this history has often been taken up to tell a victim’s story, especially in the context of 248bis. The brochure of the LGBT information center and archive IHLIA, is an example that can be interpreted as a story of vicitimization. This brochure mostly describes personal stories of people who nowadays would not be considered sex offenders. Castrations of people convicted under art. 248bis are also mentioned, for example Leo. The choices made in this brochure, however, exclude nuances and historical medical context, which could lead to a victim-villain-interpretation. The end of the castration chapter, meant the beginning of the victim’s chapter. A radio episode in 1987 takes this victimization a step further by downplaying the sexual offenses with minors and emotionally portraying people castrated in contrast to a calm and distant dr. Wijffels. The influences of emotions can also make it difficult to view this history within its context or to face it in the present, especially by its key figures. Some try to isolate their actions in the past, but some dare to reflect on it. That is why contacting and talking about these tense subjects with involved institutions is often troubled and requires courage from both sides.

Of course this history has its victims and castration was not an appropriate treatment, but we have to be aware that most of them would nowadays still be convicted as sex offender. Therefore we have to be careful for too far-reaching victimization or the denial of this past. Although it is hard, this is definitely a history that needs to be told.

Corine Bossink, Maddie van Leenders and Lisa Willemaerts