Museum Singer Laren is currently hosting the exhibition De Nieuwe Vrouw (The New Women). De Nieuwe Vrouw tells the story of the changing social positions of women, reflected in Dutch art. But is there such a thing as the ‘new woman’? And should we call her an emancipated or a modern woman? One work of art stands out: the poster Arbeid voor de Vrouw (Labor for Women) by Jan Toorop for the Nationale Tentoonstelling van Vrouwenarbeid (National Exhibition of Women’s Labor) in 1898. At first glance, the women in the poster seem to form a unit fighting together for the need for paid and useful work for women. But is this assumption correct if we take a closer look at the poster and the history of the Dutch women’s movement?

A dichotomy between women

The center of the poster depicts an imposing woman with the hammer on the anvil. Her dress is grand and draws attention. Frequent pleats in her detailed robe show that this must be a costly dress. However, some of the elegance disappears when looking at the woman’s hands. Short nails, thickened with shadows, represent the hands of a working-class woman. Like a president leading a meeting with a hammer, the central women endorses her proposal: more work opportunities for women should be implemented.

On either side of the central figure are seven women. The women appear to form a team, but close examination of the group reveals a dichotomy. The women on the right have a melancholic aura due to their gloomy looks and heavy eyelids. Furthermore, the women wear clogs. The facial expression and clothing of these women shows poverty. The thin woman on the right tries to hide her face behind her left hand and drops two white lilies on the ground with her right hand. The white lily is a common symbol of purity in fine art. The woman loses her white lilies, and with them her purity. Symbolized here are working-class women who are forced to work in factories or cottage industries to supplement the family income.

Close-ups of the women to the right of the central woman of the poster Arbeid voor de Vrouw.

The women on the left, on the other hand, are very different in attitude and appearance from the working-class women. These are women of distinction, class, and stand. With their hair pulled up, eyes made up and powder on their cheeks, they look hautain. One woman even has her eyes closed and haughtily points with her chin up. Moreover, the woman in the left corner is holding a small cup of coffee or tea neatly between thumb and forefinger, this shows a true lady’s touch. Their clothes also differ: their blouses have a more complex motif and a tighter waist belt.

Close-ups of the women to the left of the central woman of the poster Arbeid voor de Vrouw.

Above the women’s heads is an Egyptian sphinx. According to the artist, the sphinx symbolized “social evil” that oppressed and humiliated women of all ranks. The central woman seems to be in both milieus who would unite all women against this evil. Toorop may have created the dichotomy between middle-class women and working-class women to indicate that class differences should be forgotten in the fight for women’s rights. But did the aim of the exhibition match the practice?

The debate between socialists and feminists

The exhibition lasted two months in 1989 in The Hague and attracted over 90,000 visitors. This event was revolutionary for that time: never had a political exhibition been organized by women in the Netherlands. Toorop created the lithograph for the lottery where objects from the exhibition were raffled off. During the two months the exhibition lasted, copies of the poster were sold in the exhibition building and several bookstores. Arbeid voor de Vrouw is probably the best-known billboard of the exhibition and exposes well ideas of equality and solidarity within the Dutch women’s movement.

Left: photo of the main building by Anna Clasina Leijer (Atria collection, Amsterdam). Right: photo of the exhibition’s Paviljoen Voeding (Food Pavilion) by Anna Clasina Leijer (Atria collection, Amsterdam).

The women’s movement developed close ties with socialism in the late nineteenth century to promote women’s rights. But the intertwining of feminism and socialism proved controversial. Middle-class women fought for the same rights as men, specifically the right to work and education. Women from the working class, however, had little message on “the rights of women” and their “liberation”. Their priority was to improve working conditions and shorter working hours.

During the exhibition, debates arose between socialists and feminists. The aim of the exhibition was to unite women from all classes. Yet the exhibition was overwhelmingly organized and represented by middle-class women. Leading Socialist Party member Henriëtte Roland Holst-van der Schalk expressed severe criticism of the bourgeois nature of the exhibition in a pamphlet that was published during the exhibition. She argued that legal gender equality would only benefit middle-class women. According to Roland Holst-van der Schalk, only the improvement of the economic position could help working-class women.

Photo of the arranging committee taken by Charlotte Polkijn (Atria, Amsterdam). In this photo, you can see from the clothing and appearance of the women of the exhibition’s organising committee that they are from the middle class.

The power of visual sources

In his poster, Toorop distinguished two groups of women with which he subtly picked up on debates held by feminists and socialists at the time. He did not ask for money for the design of his poster. Did Toorop make the poster for ideological reasons or did love affairs also lurk behind this print?

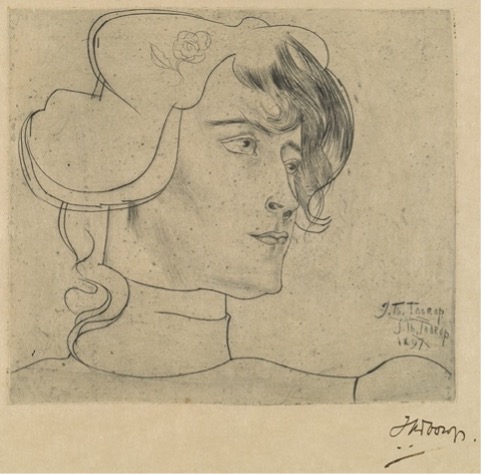

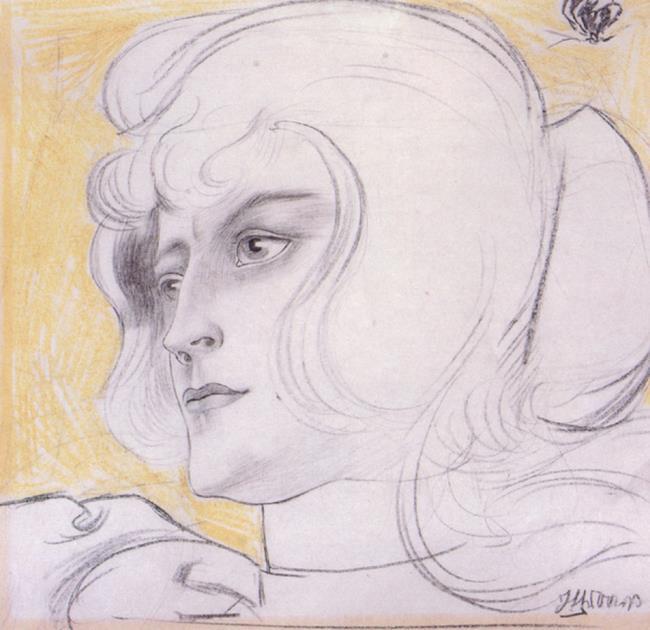

Marguérite Helfrich was a favorite model of Toorop’s. A dry needle and a drawing of hers shows that the central women in Arbeid voor de Vrouw must be Helfrich. Toorop’s portraits of her are intimate and show admiration; the suspicion arises that he was in love with her or had a relationship with her. However, this is only speculation, but two things can be concluded: Toorop harbored admiration for decisive women and criticized the bourgeois nature of the exhibition in his poster.

Both portraits of Marguérite Helfrich were made by Jan Toorop in 1897. Right: drawing (National Gallery of Art, Washington DC). Left: dry needle private collection of Ivo Bouwman, The Hague).

Arbeid voor de Vrouw was bought by the Rijksmuseum in 1915 but has been in storage since purchase. This is a pity because this visual source tells a lot about the history of the Dutch women’s movement. Fortunately, the original poster can finally be viewed again at Museum Singer Laren.

Ella Meng

Further reading:

Jansz, Ulla, Vrouwen Ontwaakt. Driekwart eeuw sociaal-democratische vrouwenorganisaties tussen solidariteit en verzet (Amsterdam 1983).

Grever, Maria, and Waaldijk, Berteke, Feministische openbaarheid. De Nationale Tentoonstelling van Vrouwenarbeid in 1898 (Amsterdam 1998).

Outshoorn, Joyce, Vrouwenemancipatie en socialisme. Een onderzoek naar de houding van de SDAP ten opzichte van het vrouwenvraagstuk tussen 1894 en 1919 (Nijmegen 1973).