Most people love an occasional drink, so what would you do when alcohol becomes illegal? You could go as far as creating a monopoly in illegal homemade wine production and trade. Because that is how far the Italian-American community in California went during the Prohibition. As a result, the Italians came to be most identified with the illegal production and sale of wine. Most simply said; to Italians, there was no substitute for wine during dinner.

Wine, War and a Noble Experiment

As the late 19th century gave way to the 20th, the introduction of prohibitionist measures was inevitable. Italian immigrants emerged as latecomers in the wine industry, taking over vineyards and wineries. We all know what happened in the teenage years of the twentieth century. But before the entry of the United States into the Great War, wine began to stand out in the state of California. Wine embodied the symbolic image of the sunkissed land, filled with olive orchards, orange groves and vineyards. It differentiated itself from other alcoholic beverages, like beer or whiskey, by the Italian monopolization of the industry and its symbolic position.

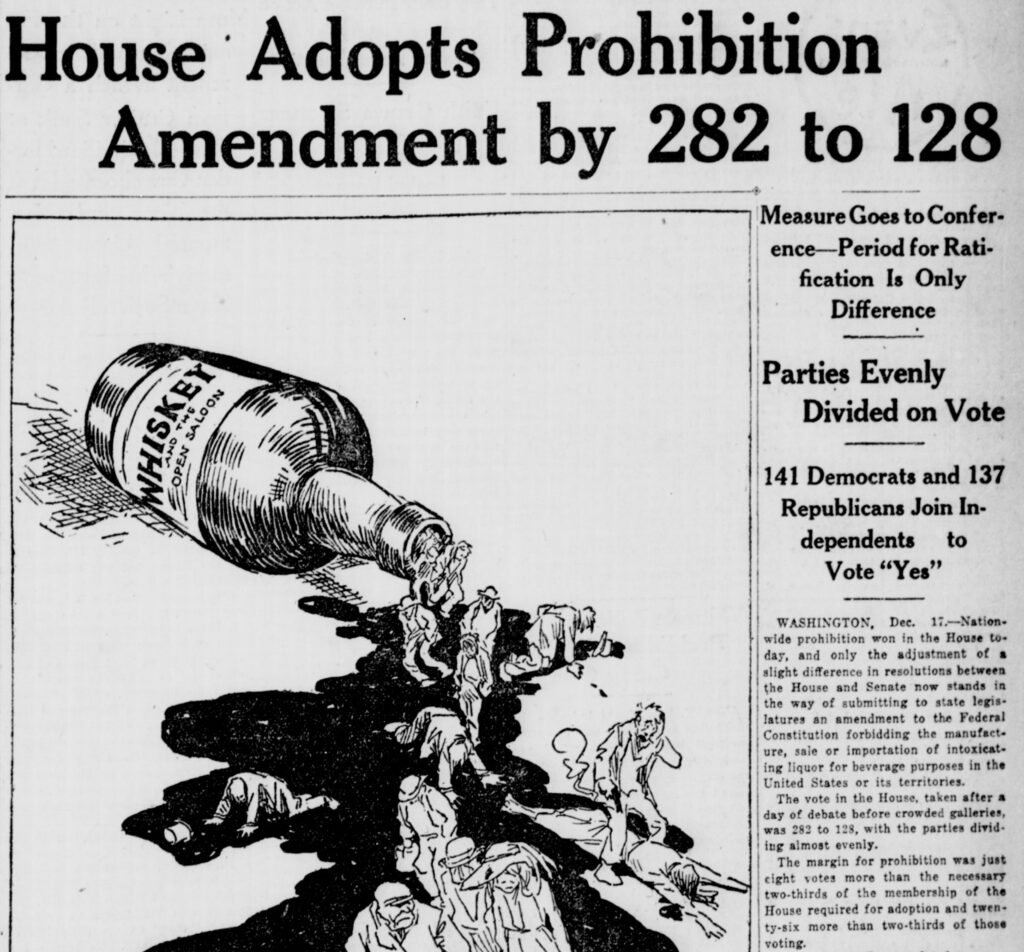

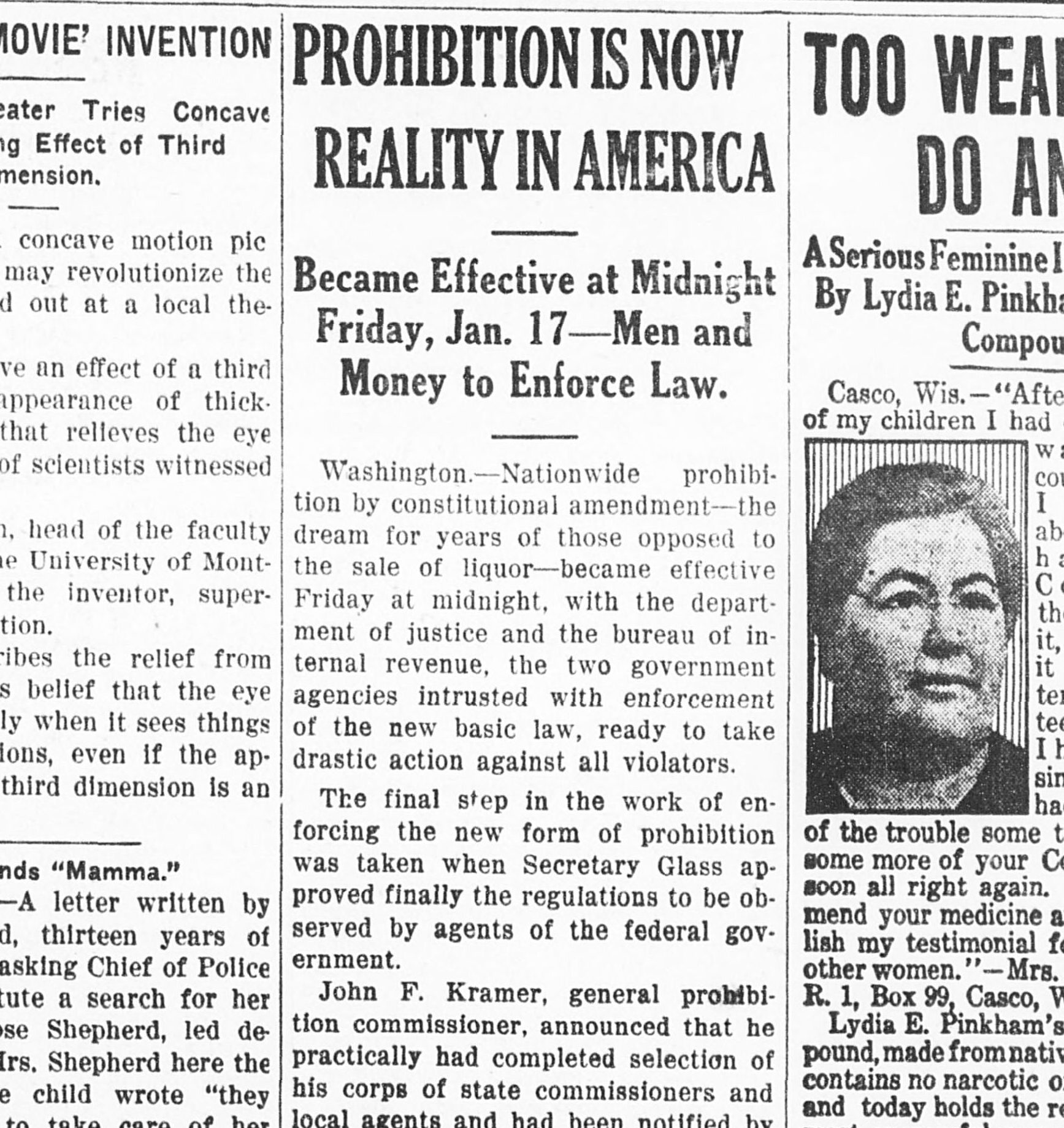

When the U.S. eventually entered the First World War, a war prohibition was set in place. This was the perfect gateway to the eventual Prohibition. The Eighteenth Amendment was passed on the 28th of October, 1919, and went into effect on the 16th of January, 1920. The United States had to abide by the rules of “The Noble Experiment”, as President Hoover later called the Prohibition.

Before the First World War, the Italians shared the dominance in California wine production with the Germans, but the scale tipped to the Italian side during and after the bloodshed. The American declaration of war against Germany instigated distrust towards anything German. The German involvement in California wine production plummeted even before the installment of the Eighteenth Amendment. Italians were on top of the Californian wine chain. However great that was, the Italians did run into some problems with the new legislation. Fortunately, they found some loopholes.

Turning Blocks into Bottles

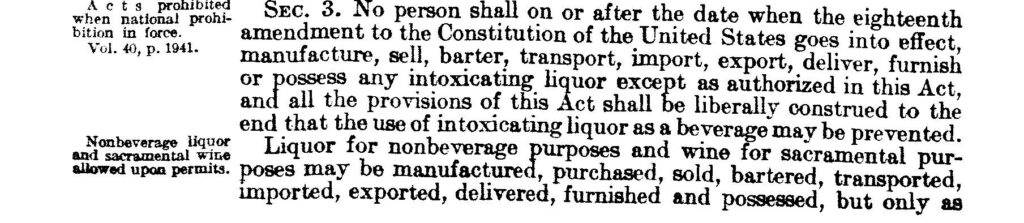

So how did Italians manage to keep drinking their precious wine? Well, the Eighteenth Amendment already contained one little exception; wine production for “sacramental” purposes. This loophole allowed Italians to set up their production for sacramental use. Besides this exception, the Internal Revenue Bureau created another by allowing more than 0.5 percent alcohol if it was consumed within your home and “non-intoxicating”. This all sounds waterproof of course, but there was one very convenient way around it. Californian wine producers could sell “wine blocks” which contained dried grapes and would not get you drunk. At least, not if you used them the right way. The wine blocks contained a warning: “After dissolving the brick in a gallon of water, do not place the liquid in a jug away in the cupboard for twenty-one days, because then it would turn to wine.” I don’t know about you, but to me, this sounds like a perfect instruction on how to make homemade wine.

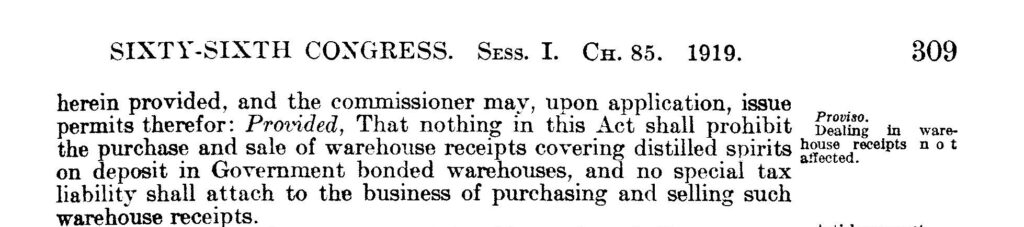

The shown images above contain text that derives from the Statutes at Large of the United States of America, from May 1919 to March 1921. These two sections (sections 3 and 29) show the exact loopholes on which the Italian community relied so heavily during the Prohibition, to be able to continue the production of their beloved wine. Plough through the Statutes here

From ‘Black Grapes’ to ‘Dago Red’

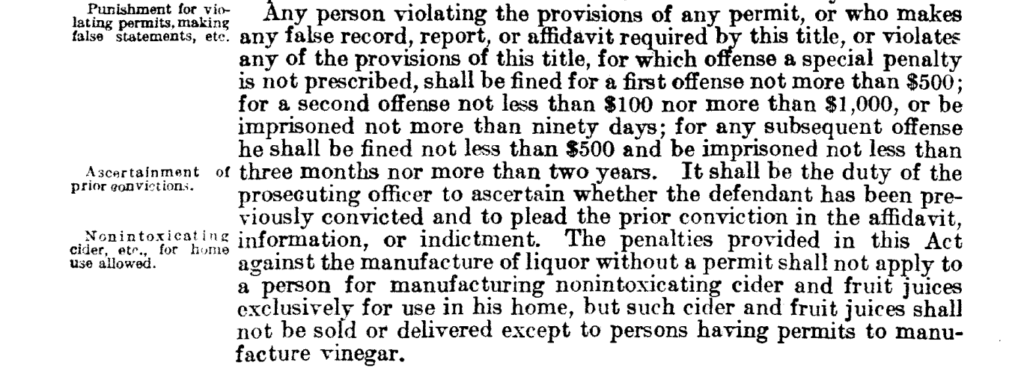

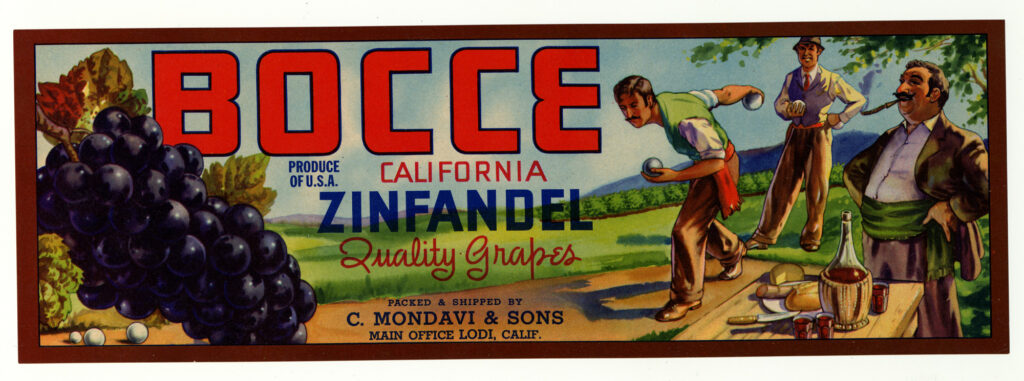

So what kind of Italian wine are we talking about and how would you recognize it? The Italian wine from California could be recognized by the crate- and wine block labels. The grapes that were produced had to survive the shipment to the other, mostly eastern, parts of the country. To achieve this feat, the winemakers preferred to use red grapes since they could survive the journey and because it was easier to make a tasty red than a drinkable white.

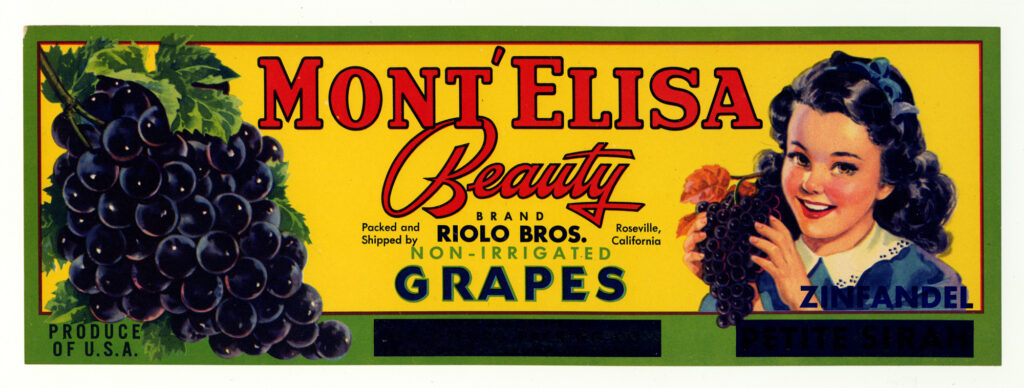

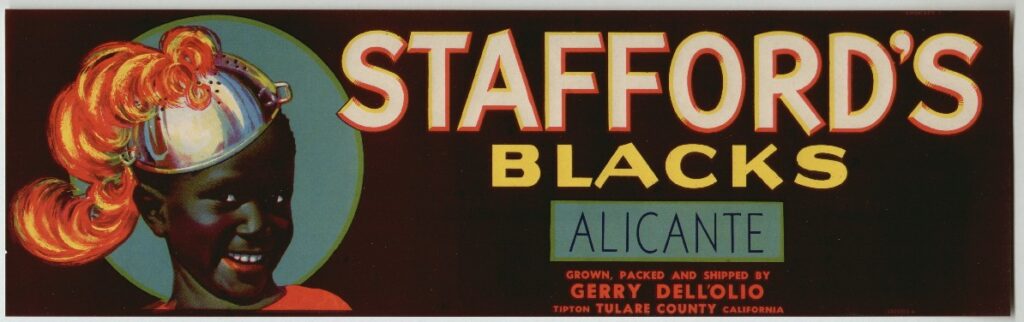

Four crate labels from Californian wine companies owned by Italians, dating back to the early 20th century. The crate labels, especially the label from C. Mondavi & Sons, depict the Italian heritage. Elements such as wine, Italian women and Bocce (a game with metal balls related to Jeu de Boules/Petanque) are shown. The crate label of Gerry Dell’olio shows the depiction of an ethnic stereotype. Read more about these crate labels on the website of the National Museum of American History

The Americans called the Italian red wines from California “Dago Red”. This term was also used as an ethnic slander for Italian immigrants. As seen above, the red grapes were sometimes termed “black grapes”, because of their dark colour. The representation on the crate label of “Stafford’s” shows the play on ethnic stereotypes that were common at that time.

Grapes on the Move

In the year 1919, California had about 300,000 acres of vineyards. It seems logical that this amount would decrease during a prohibition. Well, think again. After six years the acreage had almost doubled. Even more interesting, the shipments of grapes had grown by 125 percent. It does seem like the exploitation of the loopholes was working. So where did these grapes go? When strolling through a big city in the United States in the 1920’s, you would quickly know; the Italian neighborhoods.

“A walk through the Italian quarter reveals wine presses drying in the sun in front of many homes. The air is heavy with the pungent odor of fermenting vats in garages and basements. Smiling policemen frequently help the owners of these wine presses to shoo away children who use them for improvised rocking horses.”

New York Times, 28 April 1929, sec. 3

The quote above describes a scene in San Francisco. What the Italians were up to was evident in all, but mostly eastern, American cities. I say mostly Eastern since the communities with larger Italian immigrant populations resided here. Big numbers of grape crates were unloaded in front of houses and swiftly brought into the basements. Italian restaurants served their homemade wine in coffee cups and soft drink bottles as shown below.

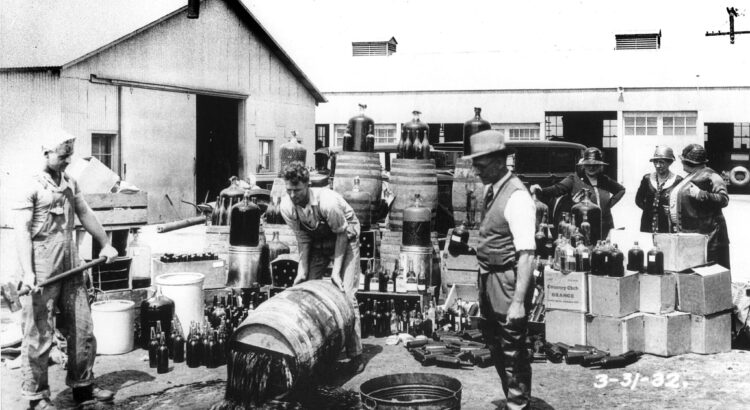

Mafia and Monopoly

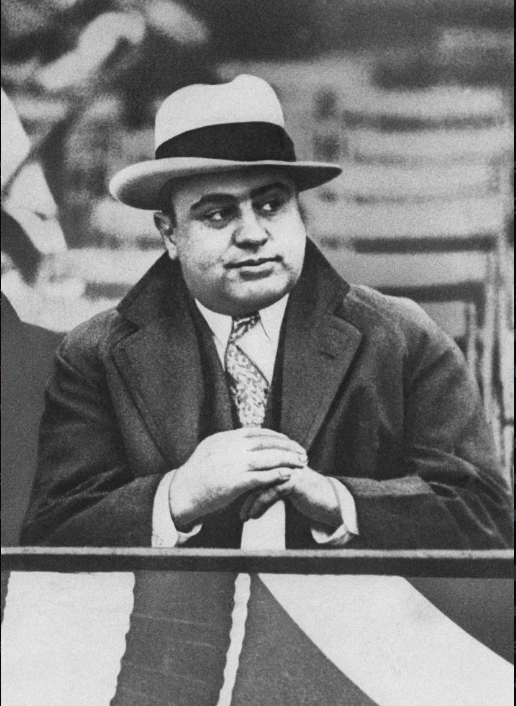

The National Museum of American History estimates that during the Prohibition period around 100 million dollars were invested in the Californian vineyards. One could only imagine how much money altogether was enticed in the illegal wine industry. The monopoly of the Italians was partly produced but mainly maintained by organized crime. This period marked the beginning of the endeavours of the modern brand of Italian mafia. They controlled the wine trafficking with corruption and violence and acquired their wealth in the process. One infamous mobster that emerged was Al Capone. He owned lots of “speakeasies” (private, unlicensed barrooms), where the precious Italian wines flowed lavishly.

We all know now how much Italians care for the continuance of their food- and drink habits. To them, their food culture is holy and nothing can replace an Italian wine. Now it’s even more clear how important this culture is to them. They will go above and beyond to ensure their habits remain untouched. Knowing what we know now, maybe we should stop putting pineapple on pizza…

Written by Bart Both

Do you want to read more?

A little bit more:

Article on First We Feast by Gemma Horowitz

Website of The Mob Museum focussing on the Prohibition

A lot more:

Cinotto, Simone, Soft Soil, Black Grapes: The Birth of Italian Winemaking in California (NYU Press, 2012).

Pinney, Thomas, A History of Wine in America: From the Beginnings To Prohibition (University of California Press, 1989).