In the beginning of July earlier this year, the Belgian AfricaMuseum (also known as the Royal Museum for Central Africa) in Tervuren requested additional funding to research the acquisition of thousands of objects from its collections. Of the 128 000 items it stores, one percent is known to be looted during the colonial era. Sixty percent of the items in the collection were bought from Africans or given by them to Westerners. How the remaining forty percent ended up in the museum collection is uncertain and needs further investigation. The question of acquisition adds a whole extra layer to the life history of an object. In this blogpost, I want to explore that layer by discussing the lifecycle of a Chokwe comb from the AfricaMuseum collection.

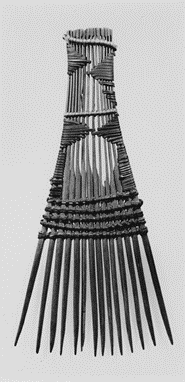

A Chokwe comb

The bamboo comb in the picture above was made and used by the Chokwe people. The Chokwe are an ethnic group that originated in eastern Angola and spread out at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth century to parts of Zambia and what is today the Democratic Republic of the Congo. They manufactured and used combs for combing and untangling the hair of both men and women. Moreover, combs also served as decorative hairpieces for men. The Chokwe are known for two different kinds of combs. The first and most collected type, are combs sculpted in wood. They come in many different shapes and sizes and often have a sculpture of a face or a person on top. The comb we are discussing in this blogpost looks very different. It belongs to the second category of combs with teeth made from bamboo and woven together at the top. Both types were equally popular by the Chokwe.

Collecting mania

On the 24th of February in 1955, a Chokwe woman sold the comb to Albert Maesen, a historian working for the then called Royal Museum of the Belgian Congo. The museum in Tervuren was established in 1898 as a colonial museum and was meant to be a space for exhibitions and research. All Belgians who went to the Belgian colony were encouraged to collect objects and bring them to the museum. Soldiers brought home weapons and trophies from their military campaigns, missionaries and western inhabitants collected everyday items. However, that was not enough. The museum wanted to collect as many objects as possible to be able to represent the ‘real’ Congo in Tervuren. Therefore it organised scientific expeditions to the colony to collect even more ethnographic items, animals, plants, etc.

One of the collectors was Maesen, who had started working at the museum in 1947. In 1954 he had become a curator and he organised different expositions and congresses. Apart from that, he also set up his own scientific mission to the Congo from 1953 to 1955. During that mission, he also travelled to Thsikapa, in the western part of the Belgian Congo, where he purchased the comb for around five francs. The complete list of objects that Maesen added to the collection during his two-year expedition is endless and covers, amongst other things, masks, musical instruments, and small statues.

Due to his great passion for collecting, Maesen had purchased a large number of combs, from the Chokwe as well as from other peoples. This considerably reduces the value of the specific comb talked about in this text for the museum collection. The comb is not only part of the more than twenty other combs Maesen collected from the Chokwe, but also of the more than one hundred Chokwe combs the museum stores in total. Moreover, many combs from other African groups have also been added to the museum collection. Consequently, the value of the comb has changed several times during its life. At first, it was a handmade comb by a person from the Chokwe culture who considered it mainly a mundane everyday item. When Maesen bought the comb, he perhaps perceived it as having an important value for the museum. However, by adding it to the museum’s large collection, it lost its uniqueness and part of its value.

A rightful transaction?

We do not know anything about how the transaction between Maesen and the woman took place. The museum is aware of the fact that even for objects that have been ‘bought’ or ‘given’ to the museum, the acquisition can still be up for question. In the deal with the Chokwe woman, for example, several aspects might have been at play that ensured that although the woman was the saleswoman, she was not in full control. Maesen was a Westerner in the Congo during a time when the colonial spirit was still strong in Belgium and that might have influenced the way Maesen went on buying objects.

No matter how the deal was made, once the comb was in Maesen’s possession, he was in control of the artefact. The comb could then be used for scientific research on the Chokwe people and culture without directly involving the Chokwe themselves. From then on, the power lay with Maesen and other Western researchers. They would be the ones deciding later on whether or not the object would be presented in the museum and in what way. In this case, it is unclear whether the comb has ever been exhibited in the museum, but the chance is fairly small. The museum itself points out on its website that only one percent of its collection is actually on display for the public and as we know, this is not the only comb in the collection.

Lisa Van den Abbeele