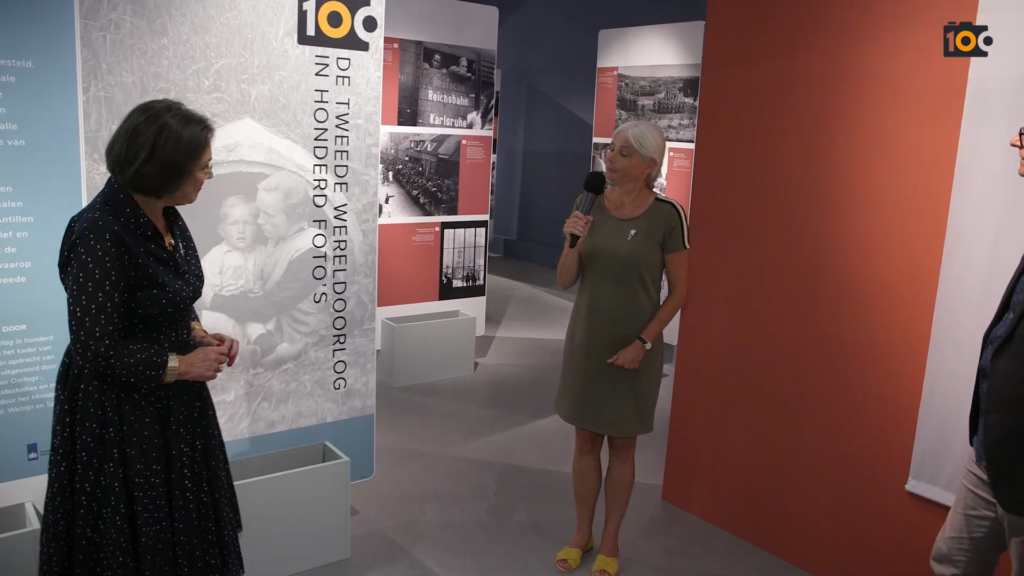

On the evening of 16 September, the long-awaited exhibition ‘World War II in 100 photos’ was officially opened through a live stream on the website of the Amsterdam Resistance Museum. Finally, after months of insecurity due to the Corona virus, the project could be shown to the public in person. However, the grand opening of the exhibition was not even its most important moment as we shall see, but merely the cherry on the cake.

The goal of the exhibition was to not only show how the Dutch experienced the war; it also wanted to show how the Dutch (want to) remember the war. In close collaboration with the public throughout all phases of the project this was achieved. It would not just be the opening which connected the past with the present, but the intensive interaction between historians and the public beforehand. The project can be seen as not only the story for the people, but also as the story as told by the people. The project is a prime example of public history done right, as we shall discover in this blogpost.

Now that the years of war and occupation are getting further and further away from us, it is mainly the images that make the past visible and imaginable.

NIOD, Dutch Institute of War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies

The project officially started as early as November 2019. To commemorate and celebrate 75 years of freedom in 2020, many projects were launched, among which the 100 photos project. As the quote above illustrates, the idea was to use photos to make the past, our past, come to life again. Through an eventual selection of 100 photos and the corresponding story behind them, the experience of the Second World War for the people in the Netherlands (and the Dutch East Indies, Surinam and the Antilles) would be shown.

Because even though most people alive nowadays have not lived through it personally, the war is viewed a huge part of our collective past, a part of our identity, something that still touches us even today and something which we should never forget. We all learned about the bigger picture – events during the war, occupation, and liberation – in school to some extent, but the way to really connect with our past tends to be more emotionally driven, more personal, something which could, for example, be achieved through a touching photograph, as the NIOD researchers describe in the earlier mentioned quote. A way to really connect could be achieved by literally picturing yourself in one of the pictures.

So, let’s get back to the start of the project: November 2019. How do you find the 100 photos that perfectly represent the experience of the Dutch during the war? The NIOD was to carry out the 100 photos project (commissioned by Platform WO2, and made possible in part by the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport and the ‘vfonds’) and asked heritage institutions, historical associations and war and resistance museums to consult their photo collections.

Additionally, the NIOD launched a campaign asking people all over the Netherlands to submit photos made during the war and occupation. This was their first step in involving the public, and people from all over the country responded. The NIOD received a lot previously unknown material found in attics, photo albums or sheds, which in itself is a very valuable achievement.

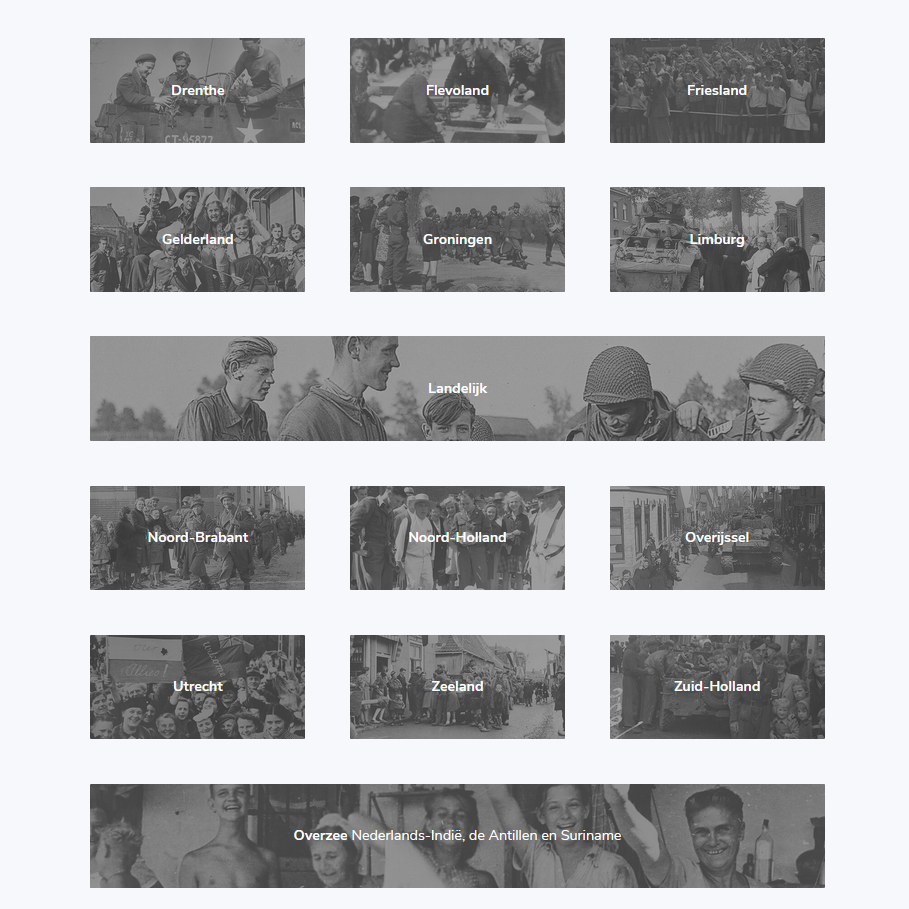

But involving the public didn’t stop there. After bringing together all known and previously unknown photographs, the NIOD selected 50 photos per province. The second phase of the project started in January 2020 when the NIOD invited the Dutch people to vote for what they felt like was the most touching or telling picture and story out of the 50 photos of their province.

The choice to hold this pre-selection at a local level should be praised: ‘picturing yourself in the picture’ and really feeling the past can be easier if you recognize a location or can identify yourself with the subject. Apart from that, it also highlights the variation in experiences on a local level: the war experience was not the same in Amsterdam as it was in, for example, Workum. The eventual 100 photos would not only reflect ‘The West’ of the Netherlands, viewing the past through a ‘Randstedelijke bril’ as some call it, but would include images from all over the Netherlands, telling the story of all provinces.

Back to the voting: people could vote during public gatherings or online, and the NIOD actively sought (local) media attention to draw in as many voters as possible. ‘We thought the process was just as important as the final result’ researcher Erik Somers explains during an interview with NOS.

The fact that people consciously look at images of history in their own area, think about them and talk about them with each other is very valuable.

Erik Somers, NIOD

The NIOD succeeded in their goal: thousands of people responded to their call and entered the public dialogue. They discussed which photos should make the cut, and thus discussed what aspects of the war should be seen as the most important to remember. The people claimed ownership over their collective past, and this debate and the subsequent selection of photos, in turn, provided researchers and historians like Somers with new insights into how the Dutch people want to remember the war, and which photos they deem as most representable of the past.

Somers was, for example, surprised that the public did not massively vote for pictures of the liberation. Instead, the public mostly opted for images showing harsh confrontations, fear and violence. ‘The Netherlands has returned from the previously cherished idea of the Second World War as an exciting, heroic period’, Somers would later conclude.

Now that the Dutch people had voted, choosing one picture out of the initial 50 photos, the ‘top 25’ per province was locally presented, after which the third phase of the project would start. A diverse jury, led by Mrs Khadija Arib, was to decide the final selection of 100 photographs from the provincial pre-selection. This selection would in turn be announced in the form of an exhibition in de Tweede Kamer in The Hague on 30 March 2020, but unfortunately got cancelled a few days in advance due to the Corona virus.

Instead, the 100 photos and the stories behind them would be made public with the launch of the official book and a beautiful and accessible website containing the final selection, on the fitting date May the 4th, the Dutch Remembrance Day. Again, the project received a lot of attention: media wrote about and praised the initiative, Dutch people and ‘BN’ers’ shared their favourite picture in videos online and smaller local exhibitions slowly opened their doors. And now, from September 17th onwards, the complete exhibition can finally be visited in Amsterdam.

The beautiful part is that it doesn’t even matter the virus delayed the exhibition. The opening would merely be the last part of a long, comprehensive and interactive project, the cherry on the cake, so to speak, but with the cake itself already being really, really good.

Long before the opening, the Dutch people were already included in every step of the project. Discussions and dialogues were already created, new discoveries were already made, and all these things were successfully shared with the public while they had to stay at home. The 100 photos project can be seen as a perfect example of what public history should be. It is an interaction between researchers and historians on the one hand, and the public on the other, a win-win for both parties, resulting in a beautiful overview of the Dutch experience during the Second World War as we see it today.

The ‘Tweede Wereldoorlog in honderd foto’s’ exhibition can be visited in the Verzetsmuseum located in Amsterdam. Visit their website to make a reservation, or browse through the photos and their stories online via in100fotos.nl.

Featured image on top, showing a mother and her son sheltering during an air raid in Markelo (Overijssel), via in100fotos.nl.

Blogpost by Magali Reijneveld