“The Deep Dark Secret of oral history is that nobody spends much time listening to or watching recorded and collected interview document”– Michael Frisch

With this quote, Michael Frisch captures the main issue of oral history; a problem which Steven High highlights in his article Public History. Telling Stories: A Reflection on Oral History and New Media. For centuries, historians have experimented with new ways to tell people stories about a distant or personal past. By using personal testimonies and eyewitness accounts, oral historians can give us an inside in the histories of certain families or communities. Over the years, those testimonies have been collected, transcripted and put always safely in an archive. But that is it. Those stories are now collecting dust in those archives, waiting for the moment to come that oral historians decide to do something with those stories.

According to High and Frisch, oral history is more than just collecting, process and store oral histories. And oral history has already changed a lot over the past few decades. Video and audio options makes it possible to include other important elements of the interviews, which were excluded in the traditional transcripted versions. The voice, the tone, body language etc. are now available, visible and collectible. Oral history is still changing. According to High it is still in its transformative state, according to High. But oral history is not just changing, its fighting off the “Deep Dark Secret”, as Frisch puts it. This Dark Secret is that oral historians do not think about what to do and what can be done with those multimedia versions of oral testimonies once they have been recorded. But this state of mind is changing.

According to High, new technologies and new media create possibilities for oral historians to interact with the oral testimonies. It is now possible for oral historians to share these oral testimonies on the World Wide Web. Oral testimonies have become available outside their dusting archives. It also affects the amount of people who are involved. During the Oral History Society conference in 2009 it became clear that there is a growing emphasis of voice. More and more oral historians prefer to hear the voice of the interviewees and communities in (digital) storytelling. In addition, according to Professor Laurier Turgeon, more ‘ordinary’ people seek interactive, participatory and living heritage and want to get involved in creating and shaping oral history. As a result of these developments, a larger group of participants are involved in creating and shaping oral history.

High substantiates his article with two of his own projects. One of them, The Montreal Life Stories Project, is a project in which oral historians spoke to five hundred inhabitants of Montreal who fled their former homes due to mass violence. The project started off as a collecting project, but as soon as the testimonies were transformed into digital stories which therefore became publishable and usable, the project grew bigger and bigger. The voices of the interviewees and the community became heard. To include those voices, there was a transparent and open collaboration needed between the oral historian, the interviewee and/or community. Therefore, the oral historians practised, what Frisch calls, ‘shared authority’. By working closely together with the interviewees, the ‘ordinary’ people get involved in selecting the clips and picking the stories. The interviewees now got a central role in creating oral history.

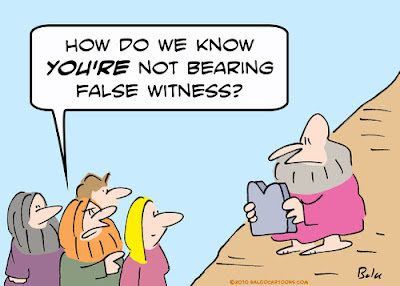

In my opinion, High has raised an important development within world of oral history. This new way of creating and telling (hi)stories opens up the possibilities for groups to be heard. It is also a good thing that (old) testimonies are now accessible for a broad audience. More and more different stories can be watched and heard in the online databases of projects such as The Montreal Life Stories Project. But I also see some issues with this kind of historical storytelling. Firstly, what about the trustworthiness of the interviewees and the verifiability of their stories? High only mentions that oral historians should closely collaborate and share authority with interviewees in the process of creating oral histories. But he does not mention how oral historians can verify the stories the interviewees share with them. Historians should always be aware of the fact that (historical) sources are never fully objective views of an event. The memory of an interviewee is always a personal interpretation of a situation. The context in which the interviewee tells and ‘relives’ the story, and by whom it is told, is very important. The oral historian should always keep in mind that someone’s past, someone’s convictions, the type of interview-questions, the setting in which the interview takes place, and the way the historian processes the testimony will influence the outcome and context. In short, (oral) historians should stay critical about the interviewees’ story and about their own working methods.

Baloo’s Cartoon Blog – Moses Cartoon by Baloo

Lotte Schouwerwou