Nowadays street names, statues and buildings are part of a heated debate about how we deal with our slavery history. Activists and some experts plead for more attention to the more controversial side of the persons we named our streets and buildings after and who we have literally put on a pedestal, like Peter Stuyvesant. These street names, buildings and statues are traces of slavery in our streets we now talk about. However, Mapping Slavery shows us that there are also hidden traces of that history in the streets – even in the smaller cities.

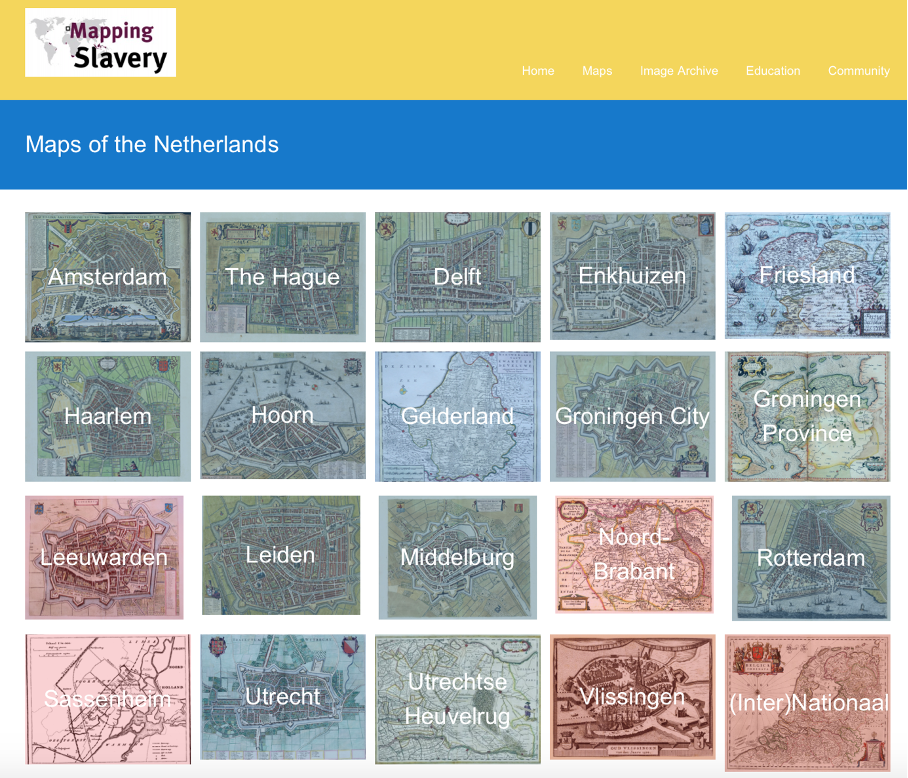

When you visit the website of Mapping Slavery, you can select interactive maps of regions and cities in the Netherlands, the United States and Indonesia. The latter is unfortunately under construction, but the first two choices contain enough maps to spend a whole day traveling through the Netherlands and United States from behind your computer. Each map is introduced with a brief historical background and some information about the traces of slavery and enslavement that are still present. The team of Mapping Slavery wants to make the public think and look differently to their surroundings, or as project-manager Nancy Jouwe puts it in an interview at NPO Radio 1: “(…) it’s about looking through a different lens.”.

When I took my own digital tour, I was surprised of how many links there can be made with the history of slavery in for instance the province of Groningen, while a big city as Rotterdam only has five pins on the map. It made me think about my thoughts about the history of slavery. I always assumed that the slave trade was concentrated in the big cities in the west part of the Netherlands, like Amsterdam. But this project definitely made me see things through a different lens – the history of slavery as well as the role of cities in it and how it is still present.

Popular education

The project was initiated in 2013 by Dr. Dienke Hondius, associate professor of contemporary history at the Free University Amsterdam, and is currently led by cultural historian Nancy Jouwe. The team exists of historians who are all specialised in the history of slavery. Because of the international scope of this project, there are many international partners. For instance, Universitas Gadjah Mada, one of the oldest universities in Indonesia, and Brown University, one of the eight Ivy-League Universities in the United States. Furthermore, the Dutch government supports the mapping of slavery in the Netherlands and America through the Consulate General of the Netherlands in New York and the programme DutchCultureUSA.

In an interview with De Groene Amsterdammer Jouwe explains the goal of the project: “What we do is popular education. We think that it is important that the knowledge about the Dutch slavery history is broadly shared. In that way, people start to think about that part of history and probably will be surprised. They probably start talking about it even more.” With this educational purpose, Mapping Slavery takes on the task of bridging the gap between the academic knowledge of the history of slavery and the demand for knowledge that comes from the public – a true task of a public historian. But it looks like this is more a one-way traffic bridge. Rather than interacting with their audience, Mapping Slavery takes on the role of the expert who educates the public – a more top-down process of writing history.

Breaking the silence

Mapping Slavery offers various ways to broaden your knowledge about the history of slavery and to see how it is still part of our daily live. The interactive maps are the main part of the project, as is mentioned before. But they also have published various guides about different cities in the past few years and these are quite a success. Some are even used by official tours in the Netherlands and New York. The guides are in Dutch as well as in English and got a lot attention in the media. Jouwe explains to Algemeen Dagblad the aim of the books and tours: “Until recently, some textbooks treated slavery as if it was only part of the American national history and not of Dutch history. Apparently, it is a difficult subject for the Dutch public. That’s why they prefer to avoid talking about it. We like to break this silence with our books and tours.”

Besides these guides and tours, the project also undertook some other activities. There are for instance some videos about slavery heritage and a series of five podcast in which the team of Mapping Slavery interviews various experts in the field of slavery history. Besides that, there is a separate website for high school history teachers and their students with material to make the history class more active.

However, the project also tries to reach the audience that isn’t consciously looking for slavery history during their city walk. In November 2018 the team placed, in collaboration with the city of Utrecht, markings before buildings were people lived who had to do something with the slave trade, acquired their wealth through it or resisted against slavery. It is just like the so called stoplersteinen in front of the houses of people who were transported and killed during the second World War. But instead of only referring to the victims, Mapping Slavery also addresses the perpetrators, historical events and objects. The markings form a slight elevation in the sidewalk, so you really ‘stumble’ over them. Nancy Jouwe talked about de stolpersteinen on NPO Radio 1: “We don’t talk about wrong and right, it is about accounting. That we share a collective history that can be found in every street and in every city.”

An active past

When I look at the project of Mapping Slavery, I think they really succeeded in their goal of popular education and to raise awareness for the role that the compromised history of slavery still plays in our lives. The different activities give every group in society the opportunity to look to their city through a different lens, whether they are walking a tour of Mapping Slavery or stumble accidentally over the stolpersteinen in the streets. It brings the passive past, which you think is far away and doesn’t affect you, suddenly close. It did for me at least.

Written by Ilse La Brijn