On the table lies a dead man’s body. His stomach is empty, his brain is visible. Behind him stands a man, whose head is missing. His hands perform a section on the brain of the corpse. On the left stands a second person. He carefully follows the actions of the man behind the corpse. In his hand, he holds the crown of the skull. Shown here is an anatomical demonstration. Would your stomach have been strong enough to witness such an event?

In 1656 Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669) created the Anatomy lesson of Dr. Jan Deijman (Anatomische les van Dr. Jan Deijman). These anatomy lessons were organized every few years by the Amsterdam Guild of Surgeons. For this occasion, the local authorities provided the corpse of an executed criminal. In 1656 this was the body of Joris Fonteijn (1633/’34–1656), also known as ‘Zwarte Jan’. He was a Flemish tailor who had gone astray and was sentenced to death on January 27 in 1656. The man behind Joris Fonteijn is Dr. Jan Deijman himself. Dr. Deijman (1619-1666) was the ‘praelector anatomiae’ (lecturer on anatomy) of the Surgeons’ Guild since 1653. The man that holds the crown of the skull is surgeon Gijsbert Calkoen (1621-1664), the assistant of the praelector.

The Anatomy lesson of Dr. Deijman (De anatomische les van Dr. Deijman) is an oil painting on canvas that was made by Rembrandt van Rijn in 1656. He left his signature on the bottom of the painting: ‘Rembrandt f 1656’. Norbert Middelkoop, curator of Old Masters at the Amsterdam Museum, argues that ‘the painting has a dramatic effect on the spectator because Rembrandt rendered the corpse in spectacularly condensed form. As a result, the dissecting table almost seems to protrude from the painting’. Photo: Amsterdam Museum (object number: SA 7394)

Group portraits of the Amsterdam Guild of Surgeons

In the seventeenth and eighteenth century the Surgeons’ Guild commissioned Dutch painters to portray the (new) praelectores and guild members to commemorate themselves. Subject of these group portraits were the anatomical demonstrations. The paintings weren’t a true representation of the anatomy lessons. Instead, they were carefully composed group portraits. According to the Amsterdam Museum, the guild thus joined the tradition of the Dutch group portrait. The paintings were commissioned to enlarge the status of the surgeons. After completion, the paintings decorated the walls of the guild room in the Waag at the Nieuwmarkt.

In 1632 Rembrandt painted his first group portrait of an anatomical demonstration: Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp (Anatomische les van Dr. Nicolaes Tulp). The Mauritshuis states that Rembrandt undoubtedly studied the three group portraits in the guild room of his predecessors before he started with the canvas of Tulp’s anatomy lesson: Anatomy lesson of Dr. Sebastiaan Egbertsz. (Anatomische les van Dr. Sebastiaan Egbertsz.) made by Aert Pietersz. in 1603, Osteology lesson of Dr. Sebastiaan Egbertsz. (Osteologieles van Dr. Sebastiaan Egbertsz.) made by Nicolaes Eliasz. Pickenoy or Thomas de Keyser in 1619, Anatomy lesson of Dr. Johan Fonteijn (Anatomische les van Dr. Johan Fonteijn) made by Nicolaes Eliasz. Pickenoy in 1625.

In January 1656, Dr. Deijman performed his first anatomical demonstration. This was probably the direct reason for Rembrandt’s commission. After completion, the painting was directly placed in the guild room in the Waag, together with the other four paintings the Surgeons’ Guild had made.

Anatomy lessons in the Theatrum Anatomicum

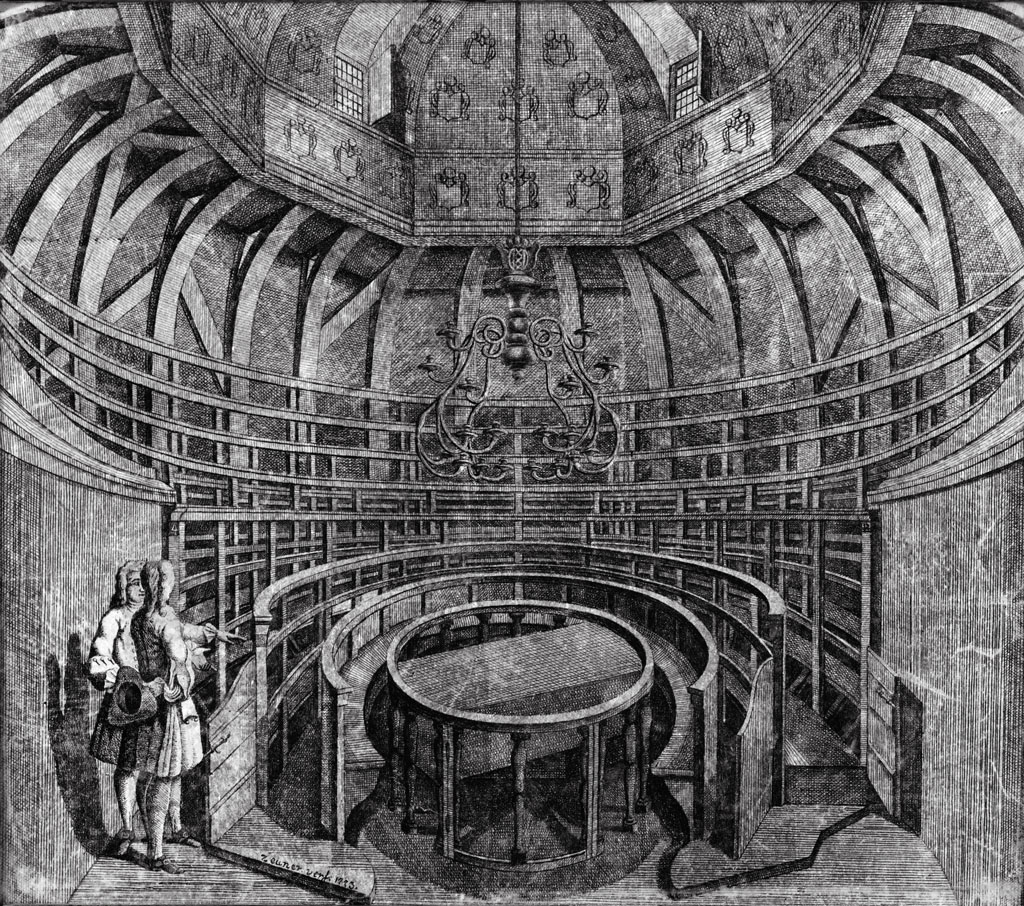

350 years ago, the educational requirements to become a surgeon were recorded in the regulations of the Amsterdam Guild of Surgeons. To become a surgeon, an apprentice was trained by a master-surgeon in a surgeon’s shop. Besides that, the praelector of the guild gave lectures in the Theatrum Anatomicum and the Hortus Medicus. Anatomy lessons, which educated the apprentices on how the anatomy of a body works, were also part of the education program. The anatomical demonstrations could last a couple of days. Therefore, the organs and the brains were dissected first, followed by the muscles, nerves, joints and bones. To reduce the bad smell, the anatomy lessons were taught in the winter. The surgical training was completed with a test of competence: the master-exam. Anatomy students and the public were allowed to watch the anatomical demonstration from the stand for a fee.

This artwork in the collection in the Amsterdam Museum gives an impression of what the Theatric Anatomicum in the Waag on the Nieuwmarkt in Amsterdam looked like. The description in the digital object registration system Adlib indicated that a new Theatric Anatomicum was realized for the Surgeon’s Guild in 1691. In the middle of this Theatrum Anatomicum, a dissecting table was placed, surrounded by a stand with eight rows of seats and standing places. Photo: Amsterdam Museum (object number: SB 5749).

The eventful history of the canvas

During his research, Norbert Middelkoop (curator of Old Masters at the Amsterdam Museum) discovered that “the painting as we know it today is nothing more that a fragment, a memory of what once was”. In 1723 a tragic incident happened: there was a fire in the guild room in the Waag and the painting was largely destroyed. Of the canvas that once measured approximately 245 x 300 centimeters, only a part of 100 x 134 centimeters (height x width) was left. The canvas got its present shape during the restoration that followed in 1732.

Art historians have concluded that a drawing that Rembrandt made on paper with ink and a paintbrush gives an impression of the original design and composition of the canvas. It shows that there were initially nine people portrayed on the canvas: Dr. Deijman, Gijsbert Calkoen, Joris Fonteijn and seven other surgeons. The portrayed surgeons appear to be looking at the spectator or focusing at the praelector. A passage in an old catalog text of the Amsterdam Museum informs us of the painting’s original background: Rembrandt situated the Surgeons’ Guild in a Theatrum Anatomicum. According to the museum, the two ascending lines – that refer to a stand – attest to this. In 1994, the Amsterdam Museum bought an attempted reconstruction of Dr. Deijman’s anatomy lesson (after Rembrandt).

This drawing (with ink and a paintbrush) of Dr. Deijman’s anatomy lesson was made in 1656 by Rembrandt before he painted the canvas. The drawing gives us more information about the composition and the original design of the painting. The drawing measures 10.9 cm (height) x 13.2 cm (width). Photo: Amsterdam Museum (object number: TA 7395).

Using digital techniques, Norbert Middelkoop and Thijs Wolzak made an attempt to reconstruct Dr. Deijman’s anatomy lesson based on Rembrandt’s drawing. To do so, they used other paintings by Rembrandt. Photo: Amsterdam Museum (object number: A 41060)

A more detailed account of the painting’s history is described by Norbert Middelkoop in the publication De anatomische les van Dr. Deijman (1994). In the eighteenth century, the collection of the guild (consisting of thirteen group portraits) regularly attracts art lovers and other curious people to the Waag. After the dismantling of the guild in 1796, the canvas was valued at only 50 guilders. After the acquisition by the Surgeon Widows Fund (‘Chirurgijnsweduwenfonds’ in Dutch), the painting was sold to T. Chaplin in England in 1842. In 1882 Jan Six bought the painting in London on behalf of the city of Amsterdam for 1400 guilders. Since 1888 the painting has been on display in the Rijksmuseum for almost a century. In 1993, the long-term loan ended by mutual agreement, so it could be exhibited in the Amsterdam Museum. The Amsterdam Museum considers this painting to be one of Rembrandt’s masterpieces:

“The fragmentary state of the canvas doesn’t take away from the fact that the painting still testifies to the genius of Rembrandt’s painting. Rembrandt’s mastery of perspective, light and, above all, the realistic depiction of the lifeless body make the fragment a fascinating painting.”

– Norbert Middelkoop, curator of Old Masters at the Amsterdam Museum, in De anatomische les van Dr. Deijman (1994)

At the moment, the painting is on display in the exhibition Panaroma Amsterdam: a living history of the city in the Amsterdam Museum.

Written by Daphne Luijters

Further reading: Middelkoop, Norbert, De anatomische les van Dr. Deijman (Amsterdams Historisch Museum, 1994).