Hummus, the blend of chickpeas, tahini paste, lemon juice, olive oil and garlic, has become one of the most beloved mezze across the world. Its popularity spans beyond just a food trend, as it is deeply embedded in the cultural and national identities of the Middle East and Mediterranean regions. However, the rise in its global popularity has reignited historical debates, turning hummus into a subject of culinary and cultural dispute between several nations. These so-called ‘Hummus Wars’ are representative of how food can be both a source of unity and division.

The origins of hummus

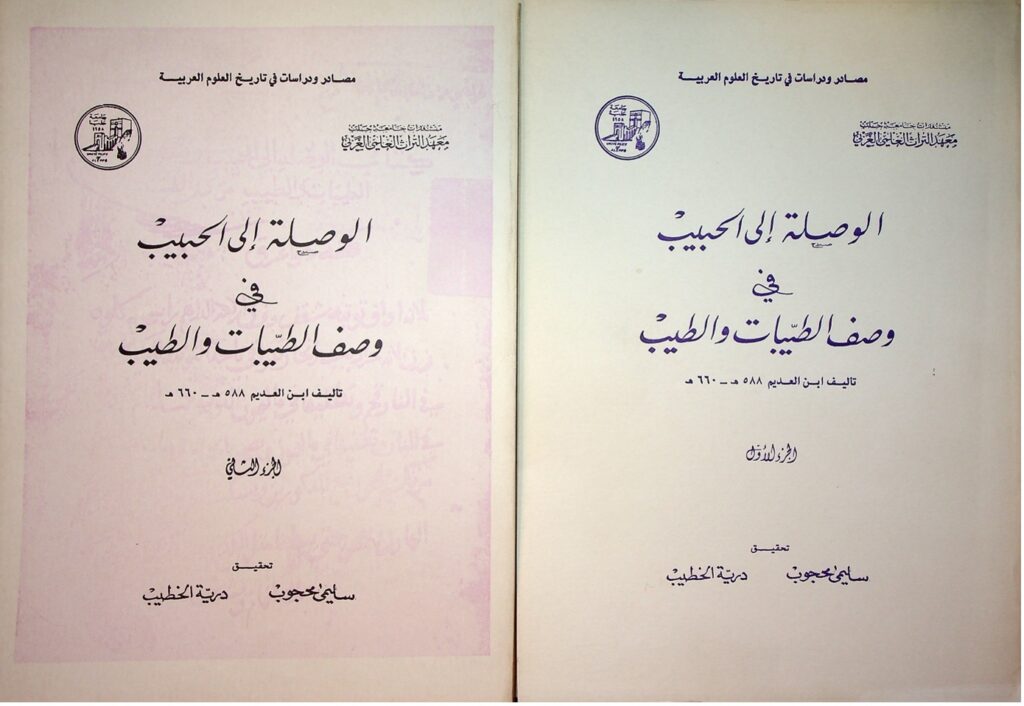

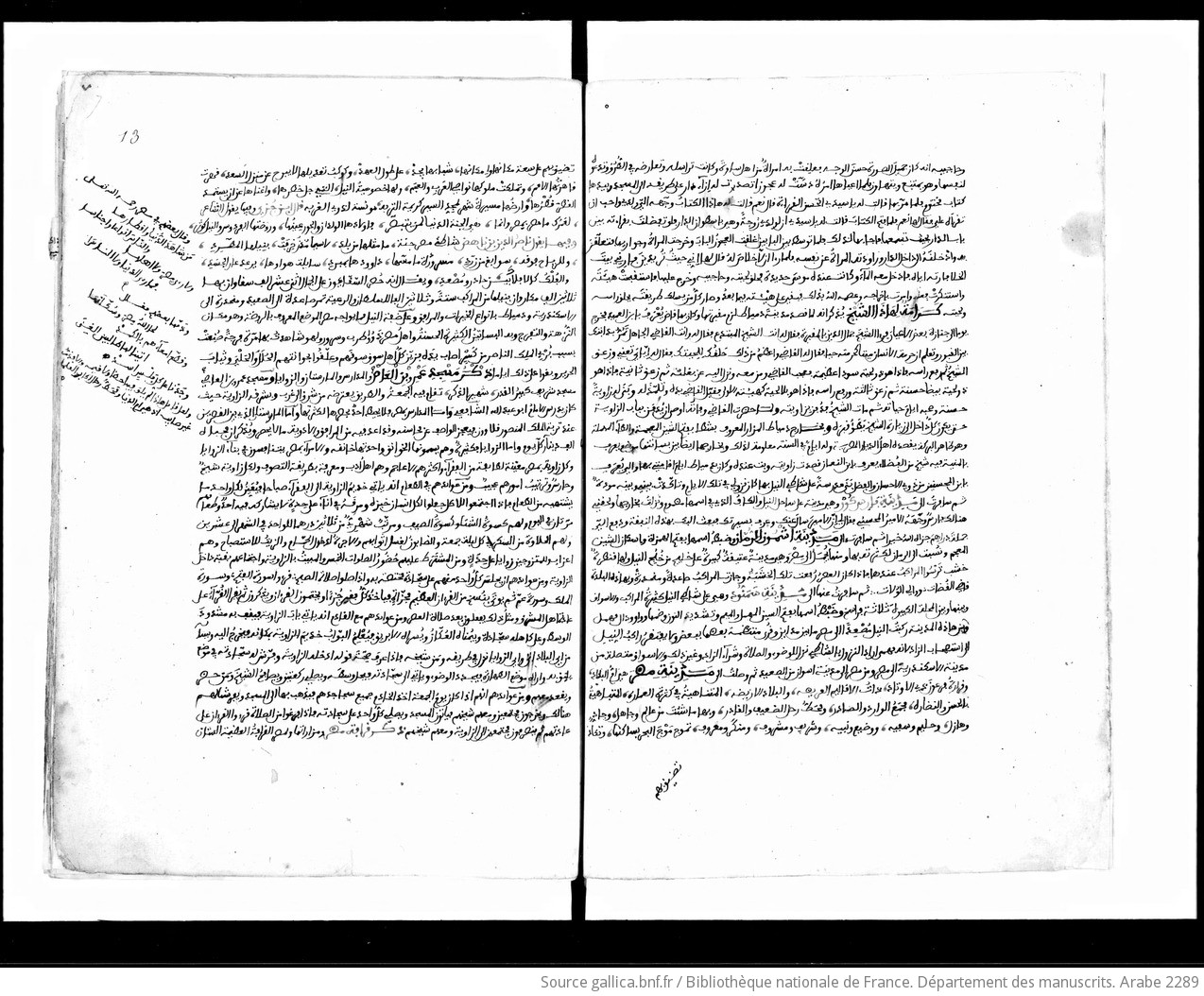

The exact origins of hummus remain fiercely debated, partly due to the dish’s deep historical roots. Scholars trace hummus-like recipes back to the medieval Arab world, particularly in the 13th century. One of the earliest known references to a dish resembling hummus appears in an Arabic cookbook titled Al-Wusla ila al-Habib fi Wasf al-Tayyibat wal-Teeb. This text, which was most likely written in the region now known as Syria, describes a recipe involving chickpeas, tahini paste, lemon, and other ingredients that closely resemble today’s hummus.

Syria’s claim for hummus is not the only one in the region. Egyptians also assert ownership of hummus, with some also suggesting that a similar dish was common in Cairo as far back as the 13th century. Lebanese and Palestinians also present historical links, with claims tied to ancient traditions that have passed down through centuries. Moreover, some Israelis cite religious texts, including references in the Bible, as evidence that hummus has deep-rooted cultural significance in Jewish history.

One of the historical sources that sheds light on early Middle Eastern dining customs, including mezzes, is Ibn Sayyar al-Warraq’s Kitab al-Tabikh (The Book of Dishes), a 10th-century cookbook from Bagdhad. Al-Warraq catalogs a variety of dishes that were served during large feasts and banquets, many of which closely resemble the small plates that are central to the mezze tradition today. While the term ‘mezze’ itself may not appear explicitly in ancient texts, the practice of serving multiple small dishes for guests to share can be traced through these early culinary writings.

While it is difficult to pinpoint a singular origin, most culinary historians agree that the roots of hummus belong to the broader Levantine region. Countries like Palestine, Syria, Lebanon, Egypt and southern parts of Türkiye all played a part in shaping the variations of this dish over time. What is clear is that hummus has crossed empires and eras, evolving into a beloved staple in Middle Eastern and Mediterranean cuisines.

Additionally, historical accounts from travelers such as Ibn Battuta and also European visitors to the Ottoman Empire provide external perspectives on the role of food and hospitality in Middle Eastern culture. These writings, combined with archaeological evidence of early food production and trade in the region, paint a picture of a cuisine deeply connected to its cultural values.

The ‘Hummus Wars‘ and The Guinness World Records

Despite its historical significance, hummus became more than just a dish in the early 21st century. In the 2000s, tensions between Israel and Lebanon escalated over who could claim the rightful origin of hummus. What began as a nationalistic pride over a traditional food became a symbol of broader cultural identity. In 2008, Lebanon accused Israel of appropriating and marketing hummus as an Israeli dish, sparking a series of events that would become known as the ‘Hummus Wars’.

Lebanon, seeking to defend its culinary heritage, launched legal efforts to gain recognition from the European Union to designate hummus as a Lebanese product, similar to the way French champagne or Greek feta cheese are protected. Lebanese officials argued that this would protect their national identity from what they viewed as cultural appropriation by Israel. Though the Lebanese efforts have not succeeded in safeguarding such a designation, the debate has continued to erupt in various forms.

Perhaps the most amusing aspect of the ‘Hummus Wars’ was the competition to set the record for the world’s largest serving of hummus. In 2009, Lebanon made an entry into the Guinness World Records by preparing a massive 2.000 kilogram bowl of hummus. Not to be outdone, Israel responded in 2010 by doubling the amount, creating a 4.000 kilogram hummus dish.

This back-and-forth climaxed in Lebanon reclaiming the title with a staggering 10.452 kilogram hummus dish, symbolically matching the country’s land area in square kilometers. This humorous yet serious competition emphasizes how hummus had become a cultural battleground, with each country seeking to affirm its ownership over the dish.

The global ‘spread’ of hummus

Despite the debates, hummus continues to thrive as an international food trend. As hummus expanded into global markets, its appeal has grown hand-in-hand with the stream of modern food trends, particularly the rise of veganism and plant-based diets. Hummus’s simplicity and plant-based ingredients have made it a favorite among vegetarians, vegans, and health-conscious eaters.

From London to Sydney, hummus has become a symbol of Middle Eastern cuisine in the West, often served as a ‘dip’ with bread or vegetables. Although my Arab-Turkish mom would wince at modern variations like ‘chocolate hummus’ or ‘avocado hummus’, the adaptability of the dish has contributed to its global success.

Hummus as a cultural symbol

Beyond the food itself, hummus and other mezzes reflects the importance of the Arabic concept of tarab, the state of gratification that comes from good company, music, and conversation. In traditional Middle Eastern homes, mezze are often the centerpiece of long, leisurely meals where family and friends gather to share stories, laugh, and enjoy the act of eating together. The small, shared plates encourages a slow pace, allowing diners to savor each bite and appreciate the range of tastes. This communal aspect is key to understanding the cultural importance of hummus and mezze in general.

Additionally, the earlier mentioned ‘Hummus Wars’ reflect a broader conversation about cultural appropriation and national identity. In the case of hummus, its widespread popularity, particularly in Western countries, has added complexity to the issue. While hummus has become a favorite health food globally, with mass-market versions in supermarkets worldwide, many Middle Eastern nations view this as a weakening of their culinary heritage.

For Palestinians, for example, hummus is not just a food but a part of their cultural identity. The dish holds special significance as a reminder of a homeland and history, particularly in the context of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. In this way, food becomes deeply political, as nations seek to protect their traditions and resist what they see as the commercialization or appropriation of their culture.

Unity in diversity?

The ‘Hummus Wars’ highlight how food can evoke powerful emotions tied to national identity, culture, and heritage. While the debates about who truly ‘owns’ hummus may never be fully resolved, what is clear is that hummus has transcended borders and cultural divides to become a shared symbol of the Levantine region. For all the contention it inspires, hummus is also a dish of sharing, and a reminder that despite the disputes, food ultimately has the power to bring people together.

If I would ask my mom what makes a ‘good’ hummus, she would most likely respond with: “love”. Whether enjoyed during a traditional Levantine meal or as a modern globalized snack, hummus represents more than just its ingredients. It carries the flavours of history, culture, and sometimes even conflict, making it a dish that is as rich in meaning as it is in taste.

Written by Zeynep Su Yaşar