Amid the Covid-19 pandemic in June 2021, an new exhibition opened in the Amsterdam Museum: ‘De Gouden Koets’. Centred around a Golden Coach, the exhibition shows this artifact of the Dutch Royal Family as its centrepiece. Six halls around the square are filled with items related to the coach wagon, which was made public after five years of restoration and a troubled public discussion. In this blog I will analyse this special centrepiece object, stationed inside a glass box in the courtyard of the museum, take a trip from its creation, usages, ‘retirement’ and discussions about its heritage and future in the Netherlands.

Standing beside the coach, it is surprisingly large. It is around 3 meters high and about 4,5 meters long. It was built, not with gold as the name might give away, but with Java teakwood, painted over with gold coloring and gold platter. Material from all over Dutch empire at the time: glass and leather form Zeeland and Brabant back home, but also with Ivory from Sumatra. There are a lot of figures, ornaments and pictures with 19th century symbolism displayed on the coach. Inside of the carriage you’ll find lots of embroidery, made women of the feminist Tesselschade-Arbeid Adelt. All over the carriage you’ll find the weapons of the 11 provinces of the Netherlands at the time, with also the city weapon of Amsterdam finding a more prominent spot. The panel paintings on both sides of the coach show different, symbolic scenes in a classical style: on the front side shows improved healthcare by lady justice and education; the right side shows a small boy throwing lilies and roses to a larger figure representing an Orang-Netherlands and elements showing different actors in Dutch society; the left side , named ‘Hulde der Koloniën’ (Tribute to the Colonies), displaying colonial wealth showing native inhabitants offering wealth and recources to an noble Orange-Netherlands; the back side showing the past with Chronos and the ‘Book of Time’ watching the inauguration of Wilhelmina. You might indeed have already noticed why, in the days of de-colonial history and the revived discussion by the Black Lives Matters movement, the object and the panel became even more controversial.

The story behind its creation is rooted with the history of Amsterdam itself. It was invented, build in, and paid for by the citizens of the city. Build in 1898, by over 1200 different labors of Amsterdam and costs were around 120.000 guilders, it was meant as a gift to the newly inaugurated Queen Wilhelmina. It was also project to connect the more disfranchised inhabitants. It had no official utility in mind, but it was first used in 1901 at her wedding to Prince Hendrik. Since 1903, it became a ‘tradition’ to use the coach on Prinsjesdag for the Royal Couple’s arrival. During this day, the Dutch King annually issues a government policy statement, presenting the (financial) policy of the government and state for that year in The Hague. During the Second world war the coach was preserved and in the immediate years after the war not used: It didn’t seem right to show the glamour in the years of reconstruction following the war, so a car was used. This was also the case in 1974 when a hostage situation took place on the same day in the French Embassy in The Hague.

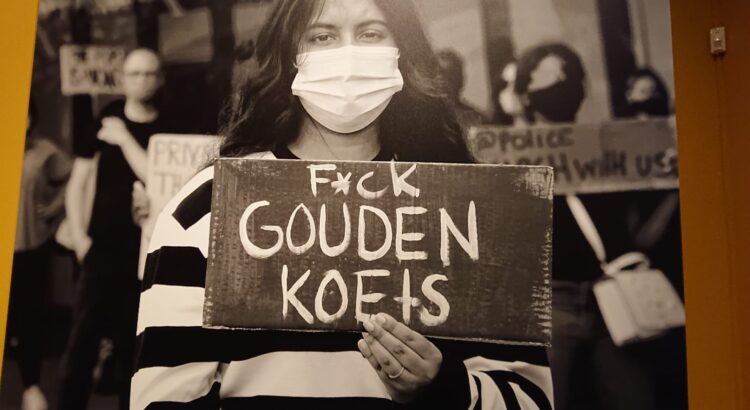

It was used all the way in the Prinsjesdag procession and special Royal occasions like weddings up until 2015. Not every Prinsjesdag or event was without incident or protest: during the wedding tour of Princes Beatrix and Prince Claus the Coach was hit by a smoke bomb and 2002 it was hit by a paint-bomb. In 1980, during the crowning of Beatrix as Queen the coach wasn’t used at all in fear of damages. Which in hindsight proved smart since the Squatters (Krakers) movement had violent clashes with the police that day. A more ironic usage was in 1954, when the Queen arrived at a meeting where the semi-independence was decide for the colonial lands of the Antilles and Suriname, with the Coach displaying colonial powers one of its panels. Before these events even, in the crisis years of the 30ties, and also in the years that it was build, the coach was also opposed by many labour and socialist movements. It was seen as a bourgeois display of excessive wealth, that was despised by the poorer parts of Dutch society. From 2011 on, but also in smaler scale before, the discussion moved to a decolonial critique, with focus now going to the panel display colonial power. How could the King, a representative of all the people of the Netherlands, go on to make present such a bad picture of our history one of our national symbols?

In 2015 the coach underwent a restoration process for a few years, stating that it was necessary to preserve it. But during the process the debate if the coach should be used again in its old ceremonial from, sparked new fires, reaching the apex with the Black Lives Matter Demonstrations in the summer of 2020. Public opinion shifted towards preservation, instead of the traditional use in the Prinsjesdag events. Among this reason the Coach was to be displayed at the Amsterdam Museum in the summer of 2021 with the museum actively asking its visitors for their opinion about the matter. The results will be presented to King Willem Alexander who will decide the fate of the coach after the exhibition ends in February 2022.

It is important to know that this blog is just a synopsis of the description and history of the ‘Golden Coach’. I recommend viewing the exhibition in the Amsterdam Museum and the publication about the coach. I think it is well done and shows the many views on the object there are nowadays, which can only provide a healing or connecting role, bringing together critics and supports of the coach in conversation. It is not certain if it will return to its former usage on Prinsjesdag, but I highly doubt it since public opinion is changing to a permanent museum spot for the ‘Gouden Koets’.

Made By Jurriaan Ozinga.