How do we deal with death? That is what it is all about at the Tot Zover museum located at ‘De Nieuwe Ooster’ graveyard in Amsterdam. The Funeral museum Tot Zover is celebrated because of its very unique concept and location. To wit, the museum houses itself in the former residence of the graveyard director/undertaker. Since fifteen years the idea already prevailed amongst the current sponsors of the museum that there ought to be a place that informs about funeral rituals and offers reflection on mortality in a broad sense.

Established ten years ago by historians, conservators and commercial businesses such as Monuta and Yarden this exactly is what Museum Tot Zover became to be. On the website it says: “The museum highlights – in consultation with partners and the public – the aesthetic, cultural and historical values of Dutch funeral heritage, with the aim of gaining more insight into how we deal with mortality”. I think too this is exactly what the museum does. In the remainder of this blogpost I’ll elaborate and try to tell you why I – after visiting this unique museum – think the place does live up to its own goals.

Visiting Tot Zover

Entering the museum you walk through the graveyard ‘Café’. Going into the museum you immediately get the sense there are no taboos here. Death being a somewhat controversial topic to talk about does not necessarily apply here. Currently the museum is having a very interesting exposition called De Laatste Aai (‘The last pat’) in which the museum denounces the funeral rituals and commemoration of passed away animals.

The permanent exhibition tries to give a historical insight in the topic while the temporary exhibitions really excel in their relevance, socially speaking. For example, in 2015 the museum held an exhibition concerning suicide, called De Vogelvanger (‘The birdcatcher’). De Vogelvanger exhibition, aluding to Papageno (one of the main characters of Mozart’s opera Die Zauberflöte), aimed to break taboos revolving around suicide and carries out the message: “Talking about it helps”. Jan Mokkenstrom, director of 113online, the suicide prevention platform, called the exhibition “a concern of vital importance”. Another example of a socially engaged exhibition from the Tot Zover museum was the exhibition about ‘selfie culture’ in combination with death. This particular idea took shape by questions people visiting the graveyard were asking the staff of the museum. ‘To what extent is it normal to make photos or videos of dead people and posting them online?’

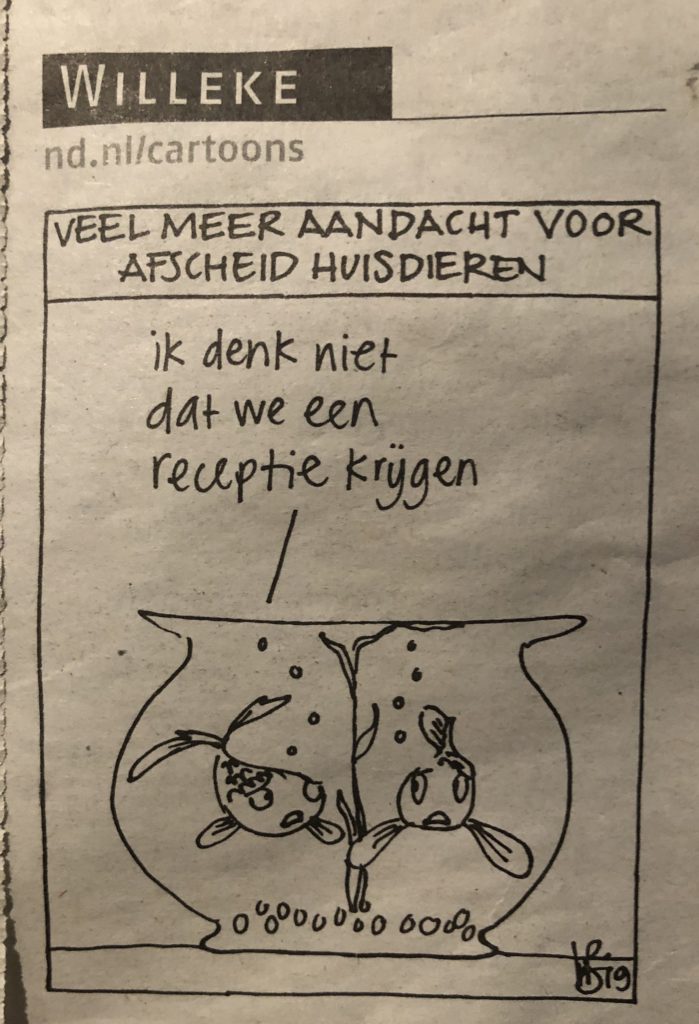

The current exhibition, De Laatste Aai, again taps into a relevant question currently discussed in society. The museum not only portrays the mourning rituals of people for their pets but also asks the question ‘why do we mourn for our pets and don’t we for all the other animals dying we eat on a daily basis?’ It’s very interesting how the museum juxtaposes the issues for the audience by supplying personal stories and objects of people losing their pets on the one hand, and arranged a room full of modern art in which is shown how animal cruelty and other animal’s deaths are viewed upon by society on the other hand.

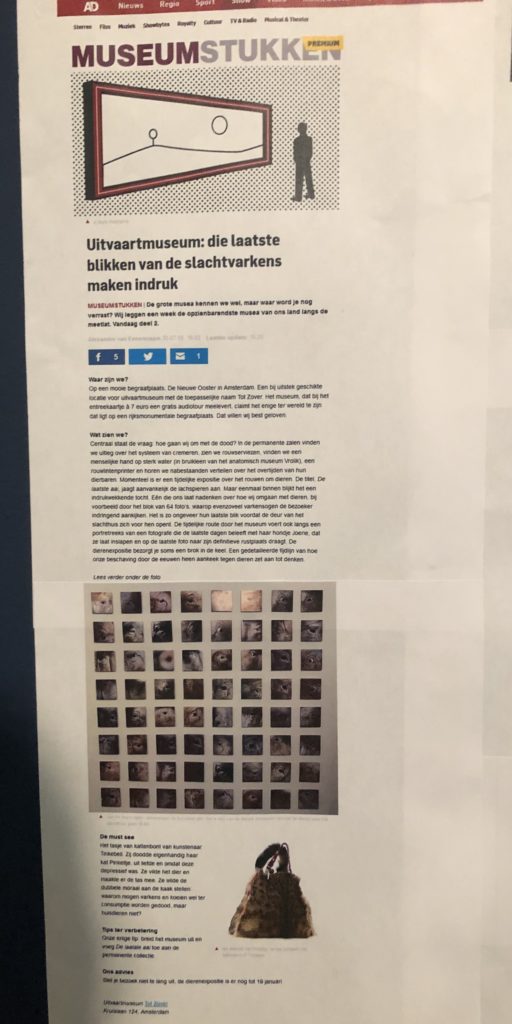

In particular the photo collection Oog in Oog (‘Eye to Eye’) put together by Tineke Schuurmans in 1962, displaying thirty to forty pictures of only one eye of different pigs before they are brought to the slaughterhouse, attracts a lot of focus on the issue (See featured picture above). Schuurmans stresses the importance of the relation between people, cultures and environment. The particular goal of the Oog in Oog exposition was to diminish the distance between the farmers business and the consumer. The pig and the spectator are really put eye to eye and it makes the spectator think about the issues Schuurmans focusses on.

55 X 80cm, (Museum Tot Zover 2015)

In conclusion, also taking in account the permanent halls, I think museum Tot Zover raises three fundamental questions or observations. First, death and funerals do not have to be stigmatized and discussion about it shouldn’t be avoided because of taboos. Especially the display of the ‘rituals room’ clarifies this. Showing us seven different manners people of different cultures partake in funeral rituals, the room stresses the need for discussion and exchange of knowledge about this topic. Secondly, Tot Zover asks the question why there is and if there should be a difference between commemorating people and pets. In addition to this, the third fundamental question concerns the difference between the general vision on how we treat pet animals on the one hand and livestock on the other hand. I would like to remark that with the current exhibition the museum revolves a lot around the animal side of things. I feel that the museum, which already includes a hall about ‘Memento Mori’ which includes a lot of animal remembrance, even shifted its main focus to animals, currently.

Tot Zover in public space and society

Apart from being a museum Tot Zover is so much more. This is where it gets particularly interesting for the public historian. Not only the museum situates itself in a public place concerning the topic (De Nieuwe Ooster), but it also has its deep presence in the society and the public space around the museum. The museum is for young and older people. It tries to facilitate a place to learn and talk about death for people from all ages and all educational and cultural backgrounds. The museum tries to include as many people as they can, since death concerns us all.

A very important link to the museum is De Funaire Academie (Scholarly platform on funeral rituals). ‘The FA’ provides the museum with academic background. The FA is the place where the academy meets the funeral industry. Based in Tilburg the FA encourages the relation between these two by writing articles on different topics and hosting workshops and symposiums. I was told by one of the museum volunteers that museum Tot Zover itself does initiate workshops like this too. For example, Tot Zover arranges workshops for undertakers so they can explain what they do to schoolchildren. You can find out much more about the FA and read their publications by clicking here.

A second important link that can be drawn from the museum to the public place is the educational program they offer to elementary schools. The museum is focussing more and more on inviting schoolclasses and invoked Kleine Hein (A parody on Jack the Ripper, suitable for kids) in the process. With Kleine Hein the schoolchildren learn and talk about death in a fun and educational way. The people conducting the tour for the children notice that rather the parents don’t like to talk about death and that the kids are very open to the idea of normalizing the notion of death. The museum also sees a lot of adolescent people visiting who are studying to become nurses or caregivers. The biggest part of the visitors consists of people already interested in the topic or with a study-wise or professional incentive. People visiting passed love ones at the graveyard don’t visit a lot in comparison to the group I just described according to the museum volunteers.

At length, I hope I have made clear that museum Tot Zover really succeeds in what they had in mind. Mortality in its broadest sense is being discussed without taboos and with respect. The notion of mortality is made accessible on lots of different levels and divided over lots of different topics which can relate to a broad public.

Algemeen Dagblad

NRC

Nederlands Dagblad

‘De laatste Aai’ received a lot of media attention from Dutch Newspapers

Het Parool

Do visit

I would really recommend visiting the museum. For more information check out the website here. You’ve got until the nineteenth of January next year before the exhibition closes and time runs out to see De Laatste Aai exhibition. If you’ve got any questions, something is not clear or you want some more information in general (since I can’t go on forever in this blogpost), please do ask or start a conversation below in the comment section.

Daniel de Ruiter