Just as a ballotin is filled to the brim with chocolates, so are the Belgian cities with chocolatiers. As a Belgian, I adore Belgian chocolate and consider it one of the best. But often with things we hold close to our hearts, we ignore its dark side. Belgian chocolate is not only a symbol of national pride, but also a reminder of the impact of colonialism. It’s important to consider the deeper significance behind the chocolate we enjoy, whether it’s a Belgian luxury treat or a simple bar you picked up from the supermarket. In this blog post, we will explore the history of chocolate, from its sweet creations to its bitter aftertaste.

The origin story

Before it reached Europe, chocolate played a significant role in Central and South America for millennia. Did you know that archaeologists found evidence of its use as early as 5,300 years ago. The Aztec and Maya primarily consumed cacao as a drink. To soften the bitter taste they flavoured it with spices and sweetened it with honey. Only the elite drank the chocolate drink during rituals and banquets. They believed that cacao was a gift from the gods, a medicine to heal the physical, emotional and spiritual body.

The European encounter: from pig drink to elite drink

When European sailors set out on their expedition in search of a new trade route to Asia at the end of the fifteenth century, their primary goal was to obtain the finest nutmeg, but to their surprise, they encountered cacao instead. During the sixteenth century, the Mesoamericans served the chocolate drink as part of diplomatic negotiations. At first, most Europeans found chocolate distasteful. The Italian traveler Giralomo Benzoni described the drink as “only fit for pigs”. Over time, many developed an affinity for chocolate. Upon returning home, colonists and missionaries, as well as Mesoamerican delegations visiting European nations, brought chocolate with them. In this way, chocolate slowly spread across Europe.

“The chocolate drink is only fit for pigs!” – the Italian traveler Giralomo Benzoni

The Mesoamerican way of drinking chocolate continued to dominate in Europe. They imitated the Mesoamerican taste and sometimes used Asian spices when the American ones were unavailable.

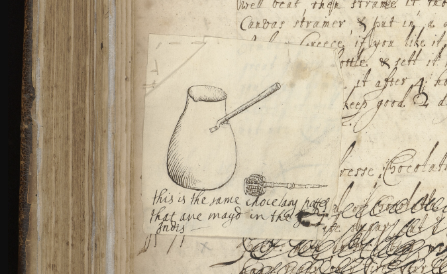

In 1635 chocolate arrived in Belgium and in 1650 in London, where the first chocolate house opened seven years later. At that time, chocolate was still rare and therefore expensive. It remained a drink reserved for the elite. The elite men gathered in such chocolate houses to discuss politics and literature over their cups of steaming chocolate. The women organised salons in their private apartments where they served chocolate in expensive porcelain pots.

The wealth of the chocolate-drinking elite was built on the transatlantic trade of enslaved African people and the exploitation of the colonial plantation system. While the upper class flaunted their expensive chocolate pots to impress guests, enslaved people were forced to work until they dropped dead. At the end of the eighteenth century, the middle class could also serve chocolate drinks. The high demand from the Western World led to further exploitation of the American plantations. In the early 1800s, numerous American colonies had risen against their European rulers. In reaction, European producers relocated numerous cacao plantations to West Africa.

“While the upper class flaunted their expensive chocolate pots to impress guests, enslaved people were forced to work until they dropped dead.”

The colonial roots

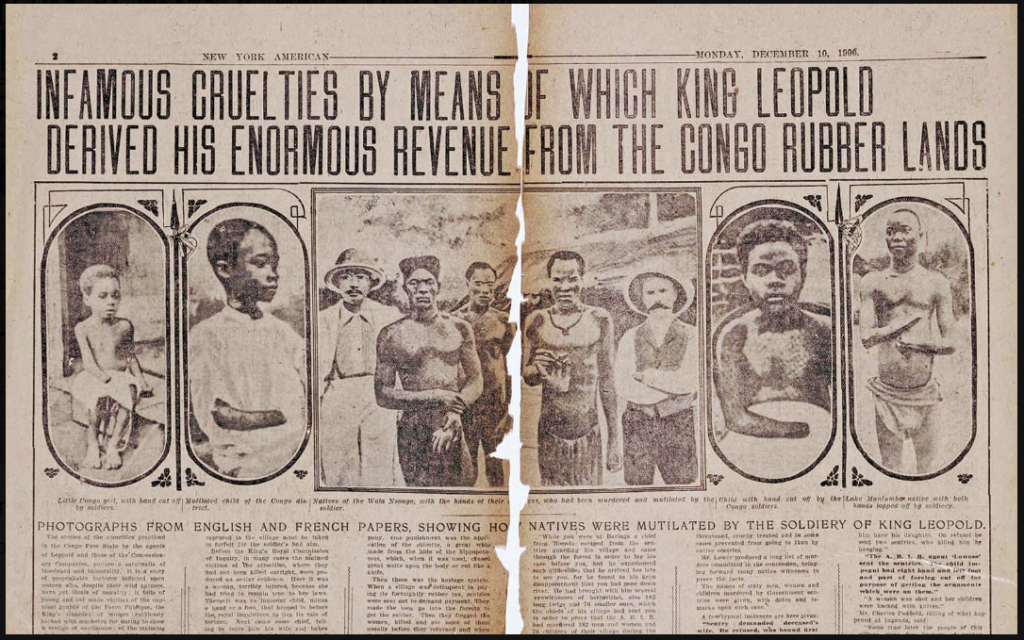

From the very beginning, chocolate in Europa was a colonial product. One of many exploited from Africa. In 1870, ten percent of the African continent was in the hands of European powers. By 1914, the number was almost ninety percent. Europe had complete control over the African people and products. During the Scramble for Africa in the 1880s, the Belgian king Leopold III pursued his ambitions to have his own colony. After some lobbying, he gained personal ownership of Congo. Driven by his desire for wealth, Leopold decided to impose high daily quotas. This resulted in gruesome acts, the most notable of which were the severed hands. This became Belgium’s shame.

Belgium experienced a second chocolate boom around 1900, culminating in the creation of the first real praline in 1912 by Jean Neuhaus Junior. It will come as no surprise that this coincides with Belgium’s colonial activities. Cocoa entered the port of Antwerp directly from Congo. There was ready access.

Chocolate today

European countries have gained recognition for their chocolate, but this overlooks the negative aspects of their production methods. Belgian chocolate is an important part of Belgium’s economy. However, it’s important to remember the troubling history of Belgian colonizers and how they exploited the Congolese people in their search for resources like cacao.

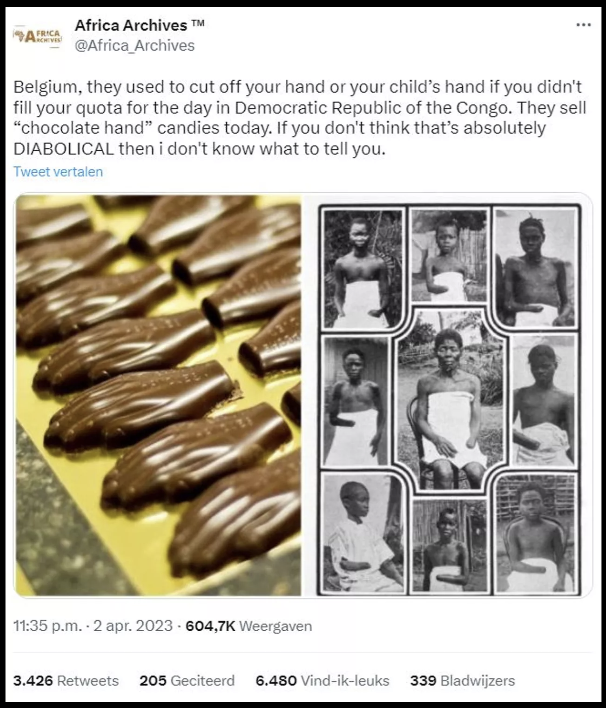

Belgium is being criticized for not acknowledging its colonial history, with an example being the “Antwerpse Handjes” chocolates. On April 2, 2023, a tweet from Africa Archives resurfaced, highlighting the connection between the chocolates and the severed hands of Congolese people during Belgium’s colonial past. Yes, you read that right. Antwerp sells chocolate hands. Despite denials from Belgians, politicians, and media, the link to colonialism is evident to non-Belgian opinion makers. Antwerp mayor Bart De Wever described it as “woke waanzin” (woke madness). In essence, the biscuits refer to the origins of Antwerp. The hands as a symbol go back to 1239. Nonetheless, De Wever places the events in separate historical spaces, ignoring the colonial past of Antwerp and chocolate. While the controversy could be an actually starting point for a debate about colonialism.

To this day slavery remains part of the production of chocolate. 1,8 million children still work in modern chocolate production. In addition, the problems in Congo testify to the colonial abuse. Fortunately there are chocolatier like Dominique Persoone who tries to distribute the prizes fairly via the project: Virunga Origins. This is the real Belgium pride.

“Consumption and exploitation interwine in ways that are so deep and fundamental that they’re hard te see.” – Social anthropologist Carla Martin.

Chocolate and Belgium are inseparable, but so is chocolate with colonialism. Sometimes we just have to bite through the bitter taste and open ourselves up to the darker sides of chocolate.

Author: Annelyn Heida