Art by Jordan Eagles used in the online exhibition Can you save Superman? for the Leslie-Lohman museum

In 1981 several, previously healthy gay men got seriously ill from pneumonia or cancer in Los Angeles, New York and California. At the end of the year 270 men suffered from (auto-)immune disease. 121 men died. Some people started calling this weird illness ‘gay cancer’. “What shows as a lifestyle of some male homosexuals has triggered an epidemic of a rare form of cancer”, says a news show host in 1981 in America. The AIDS epidemic had started.

AIDS pandemic vs. Corona pandemic [sources: Johnson & Johnson and Arab News]

In the online exhibition Can you save Superman? of the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art in New York City curator Eric Shiner wants to show through Jordan Eagles’ art how there is a connection between the AIDS epidemic of the 1980’s and the current COVID-19 pandemic. Where does this connection lie? Blood. Because AIDS was very early seen as a ‘gay disease’, the U.S. Food and drug Administration (FDA) decided to implement a lifetime ban on blood and donations from gay and bisexual men. Only since 2015 they were allowed to donate blood, but only if they were celibate for a year. In 2020, during the current pandemic where there still is a shortage of blood, gay and bisexual men need to be celibate for three months. Even though heterosexuals have the same amount of risk contacting HIV.

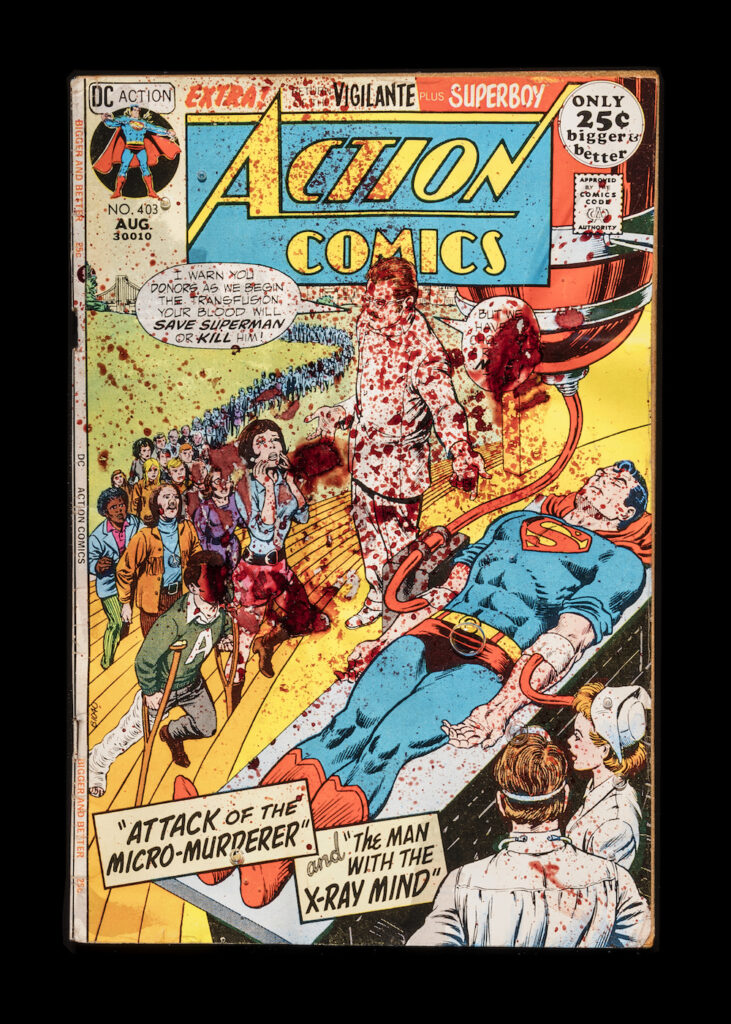

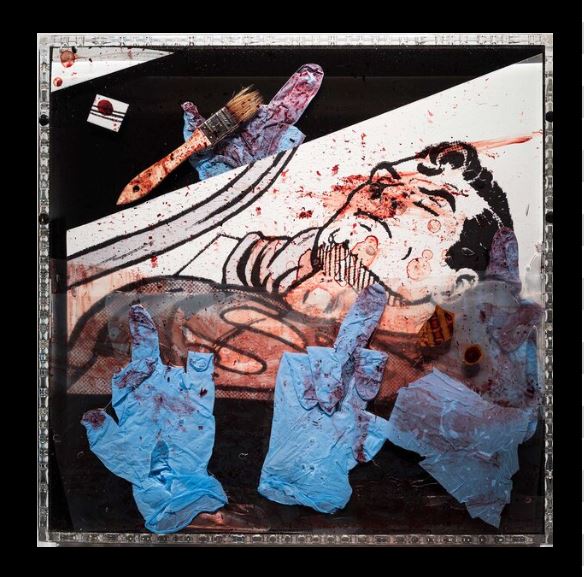

In Eagles’ art there are several images from the Superman comic book from 1971 called Attack of the Micro-Murderer. It is a story about an alien infecting superman with a supervirus. A mass call to the citizens of Metropolis ensues to save Superman. Eagles sprayed the cover with blood of a gay man on PrEP, the medication used against AIDS. This way he wants to draw attention to the “gay blood” ban.

Art by Jordan Eagles showing Superman covered in gay blood

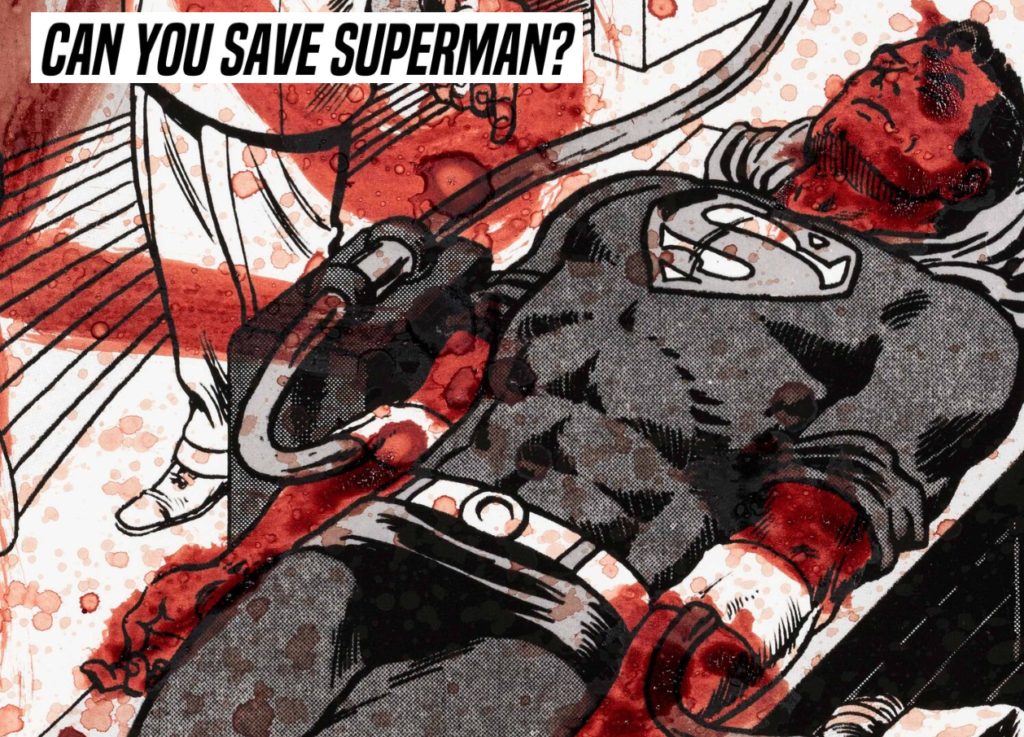

Let’s focus on the right image above us. Superman is laying down on a cushion made out of his cape. The gloves are giving him the middle finger because the blood that could save him, gay blood, won’t be used. The doctors are letting him die.

“The work is a call to action to address an evil that persists, even in light of the fact that were it to go away, lives would be saved and new heroes minted. The evil is based not in comic books, but in policy. It addresses the reality that there are still unnecessary and discriminatory deferral periods for gay and bisexual men to be eligible to donate blood and antibody-rich plasma, due only to their sexuality. It is wrong and it must end.” – Eric Shiner

This is not only a discussion in America, in the Netherlands it has also sparked debate back in March and July. Here gay and bisexual men need to be celibate for four months if they want to donate blood. Even when blood banks asked people to donate plasma, because the antibodies in plasma were needed for research of a possible vaccine, many gay men were rejected because of this regulation. One of them was Wouter Ubbink (22). He wasn’t allowed to give plasma, because he had sex with a man 3.5 years ago. “Rejecting someone after 3.5 to me is discrimination and has nothing to do with safety”, says Wouter.

The problem doesn’t lie in the Netherlands, however, but in the international agreements surrounding plasma. Those clearly state that men who’ve had sex with men aren’t allowed to donate plasma. But why are men banned for the rest of their lives when they’ve had sex with a man and not women who’ve had sex with men? Banning just gay and bisexual men makes no sense. As the exhibition wants to show, this blood ban has nothing to do with safety and all to do with a fear about gay blood that stems from the AIDS pandemic.

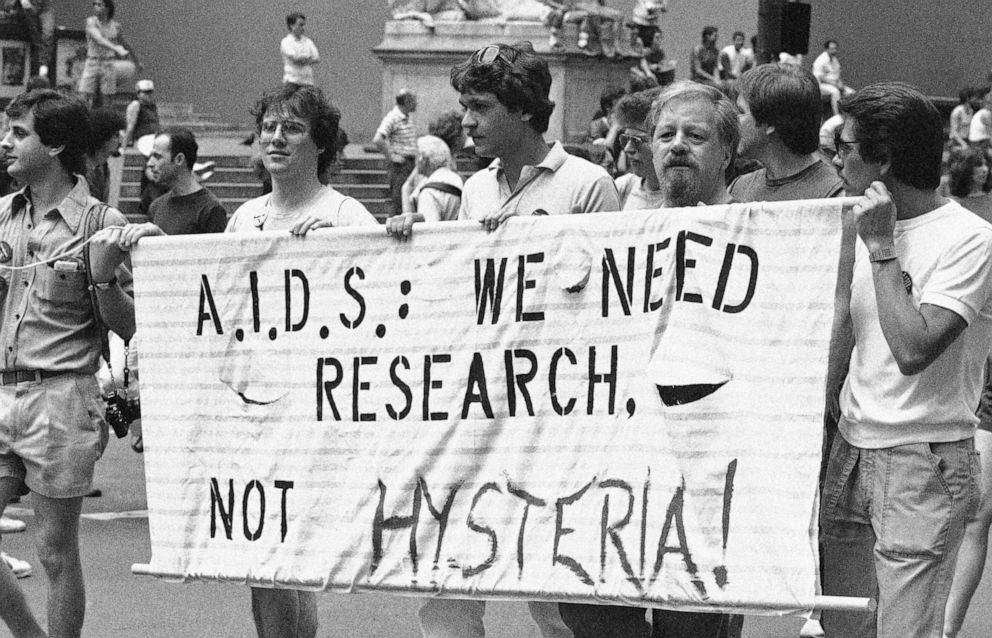

The same kind of sentiment seen back during the AIDS pandemic, gay parade New York 1983 [© Mario Suriani]

Looking more into the museum itself, it makes perfect sense why this exhibition was made for the Leslie-Lohman museum. The roots of the museum trace back to Charles Leslie and Fritz Lohman who started collecting and exhibiting gay artists. In 1987 the Leslie-Lohman Gay Art Foundation was founded and in 2016 they became an official museum. The goal of the museum is to show the “juxtaposition between art and social justice in ways that provoke thought and dialogue”. By showing us bloody pictures of Superman, the museum is trying to show us how the blood ban is discriminatory and they call for gay rights. It is the combination of an interesting choice of art and social justice that they strive for.

The question is if this particular exhibition succeeds in that goal. Visually the exhibition is beautiful and interesting, the goal and message is clear, but I’m curious how convincing the page would be for someone who doesn’t already think this way. Imagine a person that thinks in the stereotypes they are trying to battle. Someone who believes in the fear that the blood of gay men can spread HIV and that the ban is a good idea. Although the page does definitely make you think and makes you look for more information yourself, I don’t know how someone of the opposite side will react to this. It certainly sparks dialogue, but for who?

A striking image in Eagles’ art. What do you think she is thinking of what is happening to Superman?

Connected to the conviction of the exhibition is the reach of the project. Most people who are interested in LGBTQ+ rights are interested in an exhibition like this. This can be seen in the avenues where the project was shared: mostly by other websites or people already supporting gay rights. People who don’t care very much will probably never see this. An online exhibition is however an excellent tool to reach a wide public all over the globe. Spreading the dialogue through different channels would definitely help. Just as Wouter’s story made more people aware of the issue because it was posted on several news websites.

Overall, I personally liked the exhibition. For me, personally it was convincing and interesting. This sentiment is shared by the positive reviews about the project. They made a connection I hadn’t made myself and made me aware of an issue I did not know much about just yet. Now it is time to show it to more people, because having this conversation is important. Not only for a COVID-19 vaccine, but also for the gay and bisexual men affected by the ban. Wouter was told to shut up, but maybe some should listen more. Perhaps Superman could be saved that way.

Beau Thomas