It’s finally back in business: the pubs are open again, people are dancing in nightclubs and the drinks are flowing. In the countryside, people are eagerly awaiting the fair and the whole of the Netherlands is hoping that carnival will be back to normal. This is often accompanied by the necessary amounts of alcohol, something that is in the Netherlands actually the most normal thing in the world. That alcohol is not good for you is obvious, but is anything being done about it, since we are already looking forward to Friday afternoon drinks?

Not only in the Netherlands, but also in the United States and England people like to drink. Although it is often pleasant and ‘gezellig’, it also has a strong downside. Especially since the rise of the consumer society in the 1960s, alcohol consumption has increased dramatically. Thanks to shorter working days, higher wages and more time for leisure, more time was spent in pubs. Alcohol was therefore increasingly associated with sociability and also as a necessity for fitting in.

This social climate slowly but surely began to take its toll at the end of the 1960s and the beginning of the 1970s, forcing the government to take measures. Families fell apart due to excessive alcohol consumption, alcohol abuse among young people was increasing, but above all: (fatal) accidents in traffic. In 1967 the breathalyser was introduced in England, due to research from the United States, to curb the sky-high accident numbers with the Road Safety Act.

Breathalyser, 1979 TEST – Science Museum Group Collection

Introduction breathalyser by Barbara Castle (left), Minister for Transport – The Sunday Times Driving

As shown in the picture the breathalyser consists of the green plastic box with five tubes and a plastic bag. One of the tubes had to be attached to the plastic bag and then blown through the tube. The tube contained crystals that reacted to alcohol: if the crystals turned green, the driver was not allowed to drive and the blood-alcohol level was therefore too high. The company Draeger Safety Limited had a factory in Blyth from 1963 where they specialised in breathing apparatus and therefore also produced these breathalyser kits.

The breathalyser in the collection is from 1979 and is owned by the Science Museum in London. Although it is unknown when and how this object came into their collection, it is quite obvious why they acquired it. The breathalyser is displayed in the collection: Making the Modern World. Added to this collection are scientific and technical inventions that, according to the exhibition makers, have made our lives better in the past two hundred and fifty years. And indeed: this box of blowpipes has spared many lives in traffic. Despite the fact that it soon became clear that this test was not entirely reliable, and people quickly switched to the electronic breathalyser, I can imagine that the mere threat of a breathalyser control alone had a positive effect on people’s drinking behaviour.

On 1 November 1974, the Netherlands followed with an anti-alcohol law and also introduced the breathalyser in traffic, in response to falling accident figures in both the United States and England. Although the invention of the breathalyser sounds like a gift from heaven, there was however, a great deal of resistance to the introduction of an anti-alcohol law in traffic combined with testing. Many people felt that a breathalyser would restrict people’s freedom of movement and wanted to decide for themselves how much to drink on a Saturday night. In the United Kingdom a satirical programme by Frank Hall wrote a hilarious song about the invention of the breathalyser:

”but when the time came to drive home, I felt far from serene. All along the road in front of me, was forty shades of green”

John Bennett – The Breathalyser song

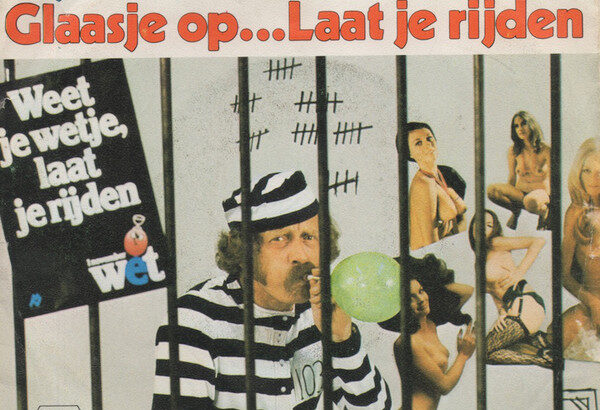

As a result of the protest, campaigns were launched everywhere to reduce alcohol consumption in traffic and to allow the breathalyser to settle down in society. In the Netherlands, this was done in a very clever way, because what better way to bind people to you than during carnival? And so Sjakie Schram’s song Glaasje op, Laat je rijden (Have you been drinking? Get yourself someone to drive you home) became a gigantic carnival hit with a bit of education for the Dutch population.

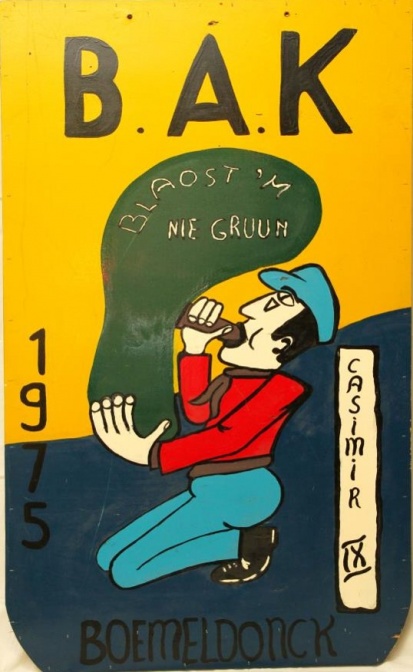

During carnival, even more carnival associations took the initiative to promote the breathalyser, as can be seen here on the poster from 1975 from the Brabant village of Prinsenbeek. Blaost’m nie gruun means loosely translated: Don’t blow the breathalyser green. In my view, however, it is paradoxical that the breathalyser was introduced in the Netherlands just before a national event where probably the most alcohol of the year is drunk. Yet it helped and the fatal road accidents, of which 3181 was the frightening figure in 1970, were a thing of the past.

And so the breathalyser from Blyth became a much hated, yet very important object for public health. Certainly in the Netherlands, the breathalyser was the starting point for many more campaigns against alcohol abuse via the government information service Postbus 51. The breathalyser has brought about a cultural change, as a result of which alcohol consumption and the associated traffic accidents have declined considerably nowadays in comparison with the 1970s. Despite the fact that plastic-bagged breathalysers have been replaced by electronic devices, the test has become a permanent practice to try and fight alcohol abuse and break the habit of drinking and driving.

And also for this weekend: glaasje op, laat je rijden!

by Nienke Spaan