What would you do if one of your loved ones died? I’m willing to guess that ‘use their hair to make a nice pair of earrings’ probably wasn’t your first thought. Many Victorians would be inclined to disagree.

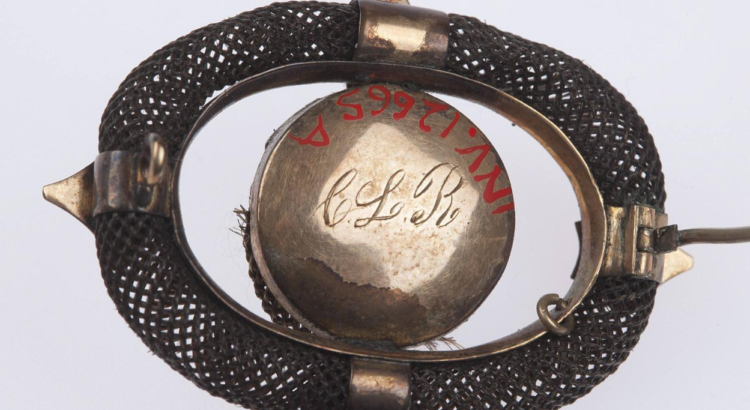

See that brown netting? That’s human hair, intricately braided and set and decorated with gold fittings. This set was made somewhere in between 1825 and 1875, when using human hair in jewelry (often called hair work) was all the rage in Western Europe and North America. The style is typical of the work made by hair workers or jewelers in New York and other American cities, which is probably where it was made.

The set was originally worn by Cynthia Longmaid Rice, whose initials are engraved on the backside of the brooch. It was then passed down to her daughter, Martha A. Rice. In 1954, Martha’s granddaughter, Nellie S. Cobleigh, gifted the set to the New York Historical Society Museum &. There, the set was part of the exhibition “Life Cut Short: Hamilton’s Hair and the Art of Mourning Jewelry” which ran from December 20, 2019 – May 10, 2020.

It’s described as “Woven dark brown hair jewelry set (mourning?)”- note the question mark. Is the set actually an example of mourning jewelry? Why did the museum assume that it had a memorial function, and what are the other options? Why would you even use hair? Let’s dive in.

New York Historical Society Museum & Library INV.12665a-c

Brooch and earrings set, 1825-1875. Hair, gold. United States, North America

New York Historical Society Museum & Library INV.12665a-c

Sentimental jewelry and hair

Cynthia and Martha lived in a time when sentimental jewelry was hugely popular. One famous fan was Queen Victoria, who commissioned highly personal pieces of art and jewelry. Some were reminders of joyous occasions, symbols of love or reminders of certain phases of her children’s lives. Others, perhaps unsurprisingly for someone who has been dubbed the Monarch of Mourning, had a memorial function. They ranged from the fairly conventional, like lockets with hair from her husband and children, to the… less conventional, like sculptures of her children’s arms and brooches with baby teeth (really).

“Hair is the most delicate and lasting of our materials, and survives us, like love. It is so light, so gentle, so escaping from the idea of death, that, with a lock of hair belonging to a child or friend, we may almost look up to heaven and compare notes with the angelic nature,—may almost say, “I have a piece of thee here not unworthy of thy being now.”

-Leigh Hunt in Godey’s Lady’s Book and Magazine, 1855

©Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Hair, specifically, has held a lot of meaning throughout the centuries. Locks of hair could be exchanged as tokens of affection between friends, lovers or relatives. In a time before photographs were (widely) available, hair could also serve as a potent physical reminder of the deceased. As hair does not decompose, it was often one of the few things that a grieving person would have left of their loved one, apart from their belongings.

Considering the emotional value, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that people wanted to encase those precious locks and keep them close. Some of the first examples of this practice come from the 17th century. ‘Memento mori’ (remember you must die) jewelry was fashionable, as was the custom of leaving money in your will so your friends could buy mourning rings. They were usually engraved with the name or initials of the deceased, their age and their date of birth and death. Skulls, coffins, and the like were common decorative motifs, and sometimes, they contained bits of hair. The hair could be placed into miniature locket fittings or incorporated into the ring itself. In the 18th century, trends shifted. Hair could be used in its natural form or crushed into paint to depict mourning scenes, usually of urns, sometimes accompanied by weeping women. These images were then set in large rings and brooches.

©Victoria and Albert Museum, London

©Victoria and Albert Museum, London

©Victoria & Albert Museum, London

The hair work craze

Still, it took until the 19th century for hair work to really take off. Up until that time, hair had mostly been used in expensive pieces of jewelry made by skilled artisans. Queen Victoria’s love for sentimental jewelry helped to further popularize it, but most people were on a stricter budget than she was. The publication of hair work guides made the craft accessible to the general public. The process, which involved washing, pinning, braiding and boiling the hair, was explained through these guides and copied at home by readers. Aside from the decreased costs, one of the advantages of going down the DIY path was “knowing that the material of your own handiwork is the actual hair of the ‘loved and gone’”, according to a guidebook from 1867. Yikes. Apparently, the flourishing of the hair work business meant that there were some doubts about the provenance of the hair that was used in professionally crafted jewelry.

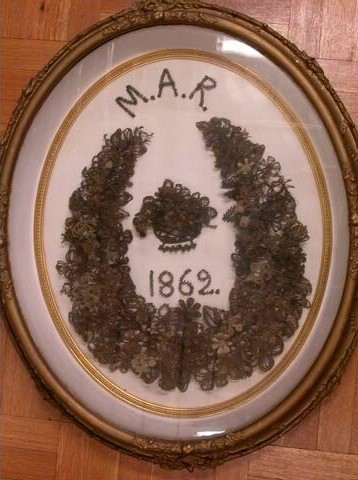

Hair work turned into a popular pastime for women, mainly those of the middle class. It was a valued skill and often seen as a way to tend to your family and home. Remember the earring and brooch set? Martha Rice, who inherited the set from her mother, was a hair worker herself. A framed hair wreath from 1862, made by a then-18-year-old Martha, was donated alongside the brooch and earrings. It took Martha two years to make the wreath, but she expanded it when her family expanded. The final work represented her, her husband and her five children. Martha’s wreath ended up winning a silver medal at a state fair.

Hair wreath in frame, 1862, human hair, beads, wood. Boston, Massachusetts.

New York Historical Society Museum & Library 1953.139

So, what’s the deal with the jewelry set? It’s not entirely clear. If it is mourning jewelry, the description doesn’t tell us who the mourner was, and who was being mourned. It’s also not clear whose hair was used in the set. Perhaps, the set was made of Martha’s mother’s hair. She may even have been the one who taught Martha how to weave with hair. In that case, the set may have attained a memorial function after Cynthia’s death. Cynthia also could have worn them to remember or celebrate her love for someone else. Through these accessories, Martha would also have been connected to that person. Or maybe, just maybe, Cynthia bought them in a store because she liked the look. Worn to mourn, a token of love or merely a fashion statement: who’s to say? Regardless of their meaning, the very material that they were made of connects these jewels to someone, somewhere.

While hair jewelry might have fallen out of fashion, we may not be that different from those sentimental Victorians. Jewelry and even tattoos containing the ashes of deceased loved ones have increased in popularity, and is keeping a picture in your wallet really that different from a lock of hair? Fairly recently, people on TikTok were turning their bra straps into bracelets for their significant others. Who knows, maybe hair work is the next step in the everlasting cycle of fashion. You should probably start practicing your braiding skills…

Written by Isa Kuijer