Each year thousands of people visit the Homomonument in Amsterdam to celebrate the pride, social and self-acceptance of the LGBTQ+ community. The monument consists of three large pink triangles that form a bigger triangle. It was built to commemorate everyone who had died because of their sexual orientation. Nowadays, the pink triangle has become a symbol that is worn with pride, but this had not always been the case. During the Second World War they were actually used to identify gay men in the concentration camps.

In this blogpost we will take a look at one of few remaining pink triangles, that is currently in the collection of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM). What stories does this object tells us and how it was reclaimed and turned into a symbol of pride?

The pink triangle as categorization

This inverted triangle is made of a lightweight bright – almost fluorescent– pink cloth and would have been worn on the left breast of the uniform. Written in the middle, with what seems to be marker, is the letter “T”, presumably short for Czechoslovakian. The color of the badge corresponded with the reason why you were arrested and sometimes an added letter would indicate the nationality of the prisoner. It is not known by whom this particular triangle was made, but we do know where it was found: the Langenstein-Zwieberge concentration camp. On the 22nd of April 1945, Colonel Charles F. Ottoman discovered it, after the camp had been liberated eleven days prior. He brought it back with him to the United States and it was transferred to the collection of the USHMM in 1991. According to the website of the museum, the patch shows no sign of use.

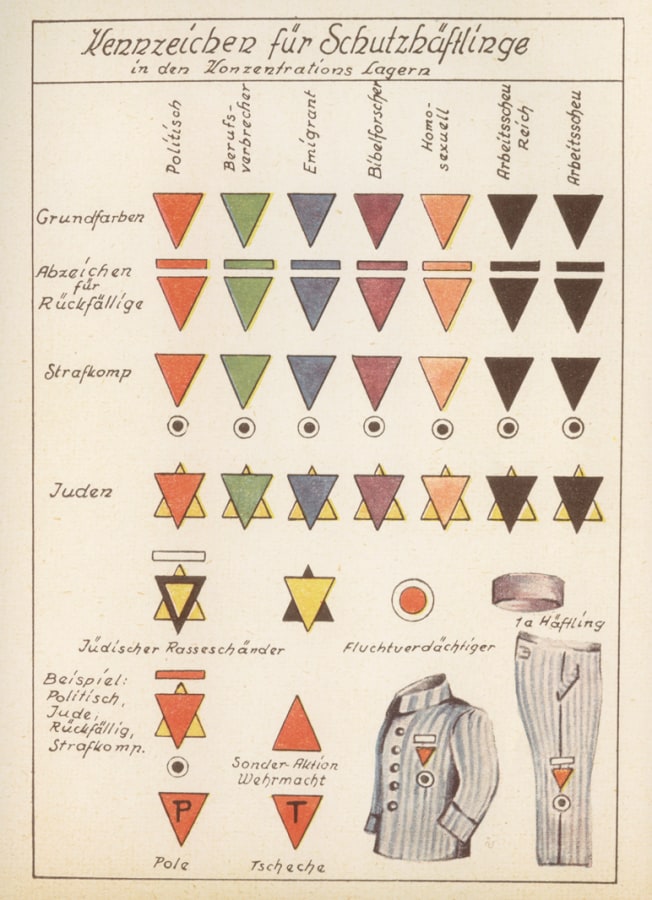

Badges in different colors were used for corresponding categories of prisoners, as you can see in this chart. Pink was used to identify homosexual men, bisexual men and transgender women. The yellow star indicated the Jewish people, as you probably already knew. The red triangles were meant for possible threats to the Nazi-regime, such as the communists and the social democrats. The black badges were used to identify the Sinti, lesbians, those who were considered to be mentally ill, and people who were addicted either drugs or alcohol.

Before the pink triangle

Before the lives of the LGBTQ+ people were dramatically changed due to the War, the gay and lesbian scene in the Weimar Republic was flourishing. In the 1920s and up until 1933, songs and movies were written about what it meant to be attracted to someone from the same gender, there were about one hundred lesbian and gay bars, and Magnus Hirschfield established the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft. Hirschfield, a gay man himself, wanted to create a safe haven for the LGBTQ+, where they could read about sexuality and gender. Homosexual activities were officially still criminal according to Paragraph 175 of the German Criminal Code that had been implemented in 1871, which prohibited sexual relations between men, but the notion was that people were monitored and not really persecuted. A parliamentary committee had even recommended to erase it.

However, this changed when Adolf Hitler rose to power in 1933. No longer were people considering erasing Paragraph 175, the opposite happened. It was revised to be more punitive. The version from 1871 had read: “Unnatural sexual acts (‘widernäturliche Unzucht’) committed between persons of the male sex, or by humans with animals, is punishable with imprisonment; a loss of civil rights may also be sentenced.” After the revision under the Nazi-regime it was changed into:

“A man who commits sexual acts (‘Unzucht’) with another man or allows himself to be misused for sexual acts by a man, will be punished with prison”.

– Paragraph 175, And the Nazi Campaign Against Homosexuality, Holocaust Encyclopedia

The Nazi’s wanted to get rid of the gay men (or those who identified as such) because they were considered a threat to the purity of the Germans. The Paragraph was enforced, the library of the Institute was burned down, and any homosexual activity was prohibited. As a result, more then 100,000 men were arrested, and many were sent off to concentration camps in Germany such as Auschwitz and Dachau. Sometimes they were even put in separate “sissy blocks” out of fear that they would interact with the other prisoners and spread their homosexual tendencies.

Between 5,000 and 15,000 carriers of the pink triangle eventually died, which is estimated to have been 55% of the gay prisoners in total. Compared to the death rates of other groups that had to be ‘reeducated’ according to the Nazi-regime, such as political prisoners’ of around 40%, this number was extremely high. Gay men were forced to work longer shifts under terrible weather conditions and were more physically challenged, because many Nazis were convinced that hard labor could “cure” their deviant preferences. Numerous homosexual men were also castrated and experimented on. During one experiment men were injected with male hormones to see if their sexual preferences would change.

Shame turns into pride

When the war ended the prisoners who had worn a pink triangle, couldn’t seem to escape it. Homosexuality was still considered to be a crime in East and West Germany until the late 1960s and many of the survivors couldn’t go back to their families. They couldn’t bear the shame that people knew they had been wearing one. Richard Plant, who was gay and jewish himself during the War, published in 1986 his book called “The Pink Triangle: The Nazi War Against Homosexuals” in which he concluded the following:

“Despite the fact that they no longer had to wear the pink triangles that designated them, they remained marked to the end of their lives.”

– Richard Plant, The Pink Triangle, citation from Memorial and Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau

How did this symbol of shame turn into one of pride? During the 1970s the image of the pink triangle was reclaimed by activist gay liberation groups, such as the Homosexuelle Aktion Westberlin, who wore the symbol – this time by choice – to pay respect to the people who had died because of their sexuality. From that time on, the meaning of the symbol has changed. It is no longer a way of categorizing people against their free will, but a badge that is worn with pride. By wearing it, the victims of the past are not forgotten, and it shows us how far society has come. At the same time, however, it is a reminder that we still have a long way to go.

Emma Sow