Recently, there has been a renewed interest in restricting the rights of prostitutes. Prostitution is legal in the Netherlands, as long as the concerned party has a permit. The Netherlands are an exception in how they deal with topics such as prostitution and drugs. While some people are still discussing whether the legalizing of prostitution was a good idea to begin with, the fact is that prostitutes have exceptionally beneficial working conditions in the Netherlands. This was not always the case: in the 90’s prostitutes were driven out of the city center. This is where union De Rode Draad stepped up: an organization that defended the interests of prostitutes. Among their goals was a request to the government to stop the ‘hunt on hookers’. How did prostitutes fight for their rights in the 90’s and what history can a pavement tile tell us?

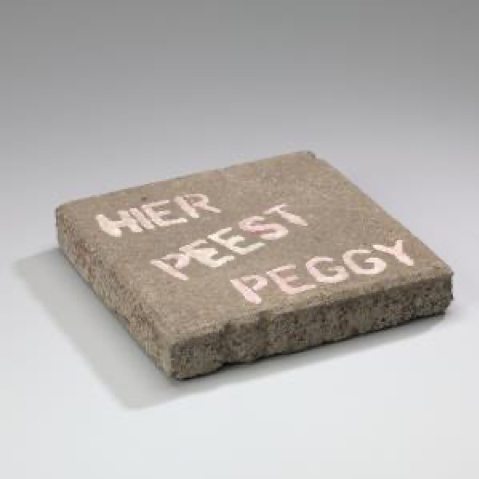

Figure 1: pavement tile from De Rode Draad (5.4 cm x 30.3 cm x 30.0 cm) with the slogan: “HIER PEEST PEGGY” 1993. Source: online research collection Amsterdam Museum (inv.nr. 191).

Just a sidewalk

Before it was decorated with paint during the protest in 1993, the stone you see above was nothing more than a sidewalk. It was probably situated around Amsterdam Centraal station: the only legal area where prostitutes could still meet with their clients. Throughout the 1980’s the Dutch government launched a new set of rules to regulate streetwalking in cities such as Amsterdam, Utrecht and Rotterdam. Public activities such as those affected the reputation of these respective cities. Neighbors were also not pleased with the streetwalking because it affected their ‘peace and quiet’. In 1993 the city council banned all related activities in the public, thereby actively disabling prostitutes from doing their job. This sparked the protest of De Rode Draad, a one-of-a-kind union for prostitutes. Their goals were to legalize prostitution, improve the position of prostitutes in society and to stimulate the public debate on topics such as: hygiene, safe sex and human trafficking.

On this corner works Corrie

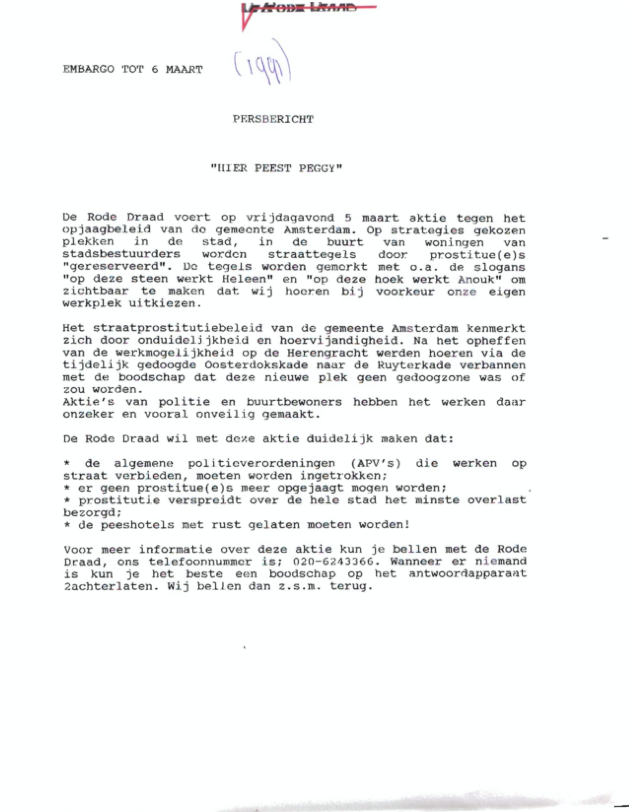

On the fifth of March in 1993 a group of fourteen people came together at night to protest the new ban on streetwalking behind Amsterdam Centraal. During the protest it was raining all night. For this reason the graffiti, which they used to paint their slogans with, kept washing away. But it wouldn’t stop them from continuing to paint their alliterating slogans on the pavement tiles. They used slogans such as: ‘Hier peest Peggy’ (if translated to English it would be something like: ‘On this corner works Corrie’). Union De Rode Draad organized the protest and released a press statement the following morning: indicating that getting the attention of the media was the primary goal (see figure 2). It was the start of a battle that would last for years between De Rode Draad, the municipality and the local residents.

Figure 2: press release De Rode Draad Source: Sekswerkerfgoed.nl

Removal and donation

It is quite unknown how the pavement tile was removed after the protest and who was therefore responsible. When looking at the press release it is made clear that De Rode Draad was aware of the importance of their protest. That is why it is not unlikely that they removed the tile from the streets themselves. Probably because they wanted to remember this act of resistance. In 2009 the office of De Rode Draad closed due to budget cuts and a decrease in members. A few years before that in 2002 the Amsterdam Museum organized an exposition on prostitution in Amsterdam called ‘Liefde te koop; vier eeuwen prostitutie in Amsterdam’, which translates to: ‘Love for sale: four centuries of prostitution in Amsterdam’. That is probably why the pavement tile ended up in the Amsterdam Museum as a part of De Rode Draad’s considerable donation in 2010 along with other objects, books, and pictures. The current curator specialized in prostitution rights at the Amsterdam Museum could not tell me if the donation was initiated by De Rode Draad or the Amsterdam Museum.

‘The Hoerengracht’ and ‘Work, Body, Leisure’

In March 2010 the Amsterdam Museum opened their second exposition on prostitution. The second exposition: ‘The Hoerengracht’ focused on the relationship of art and the red-light district in Amsterdam. The pavement tile was displayed for the first time next to other objects donated by De Rode Draad such as lingerie, books and condoms. In 2018 the pavement tile traveled all the way to Italy. It was part of the Dutch contribution on the Architecture Biënnale in Venice called ‘Work Body Leisure’. In this exhibition the tile was displayed next to a protest sign against streetwalking which was made by Dutch locals (see figure 3). The pavement tile and the pimped stop sign symbolized an ongoing tension between different interests in the public sphere.

Figure 3: stop sign (60.5 cm x 60.5 cm x2.7 cm) made by resident (Ed Müller) against streetwalking. .Source: online research collection Amsterdam Museum (inv.nr. 190).

The life of an object

With multiple political parties wanting to reimplement the ban on prostitution today, it is hard not to compare this situation to the tension around streetwalking in the nineties. The centerpiece in this blogpost gives us a better understanding of where the unique Dutch policy around prostitution originates from. I didn’t expect to learn so much about history of the Dutch prostitution policy by just looking into one specific object, in contrary to visiting an entire exhibition. It made me realize how much goes into the process of curating. The gathering of objects and how these fit into a museum’s collection shape exhibitions more than I thought. I’m curious what the future will bring for this pavement tile, especially now that the rights of prostitutes are again being debated.

Mara Werner

Interested?

Sekswerkerfgoed, Korte geschiedenis van De Rode Draad, https://sekswerkerfgoed.nl/korte-geschiedenis-van-de-rode-draad/ (Accessed 29 September 2021).

OVT, De wallen en prostitutie in Amsterdam (27 april 2008) https://www.vpro.nl/programmas/ovt/speel~POMS_VPRO_206437~ovt-27-april-2008-uur-1-21-min-de-wallen-en-de-prostitutie-in-amsterdam~.html (Accessed 30 September 2021).