In 2006 Jeff Howe used the word ‘crowdsourcing’ for the first time in his article for the technology magazine WIRED entitled ‘the Rise of Crowdsurfing’. Ten years after Howe published his article, crowdsourcing has not only shown to be very useful, but also more and more common in our ever growing digital world.

Through crowdsourcing projects such as velehanden.nl, fold3, Demogen or Itinera Nova were made possible. In these projects volunteers (mostly amateur-historians) worked under instructions of archivists or historians to digitize or unlock (primary) sources mostly found in archives. Like Robert S. Wolff states, most of the historians will embrace the fact that thanks to crowdsourcing, electronic access to published scholarship and primary sources has drastically increased.

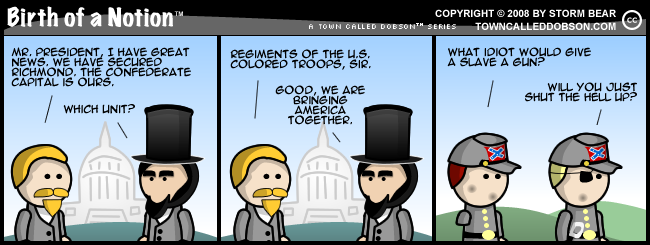

The digital revolution nevertheless does not stop with the digitizing of sources. This revolution democratized historical practice in general. Suddenly, a lot of material that used to be seen and analysed mostly by schooled historians, was available for everyone with an internet connection; this very large public could read and interpret sources in their own way and spread their findings over the internet through various mediums. The schooled historian suddenly had to share his authority with a million other people that criticized him and did not always believe what he stated, because when these people read the sources, they saw a different truth. This is exactly what happened in the Black Confederate Soldier debate that Leslie Madsen-Brooks described in her article.

A black and white debate in a grey zone

I agree with Madsen-Brooks that history in the digital space can be ‘shallow, often uninformed and frequently decontextualized’. With her article, she indeed opens a very interesting discussion about the problems of authenticity and credibility crowdsourcing can bring. Nevertheless I think that at the end of the line, these questions are not the most relevant ones the historian should ask himself when reading historical information on the internet. Just like Madsen-Brooks states correctly whilst quoting Kevin M. Levin: ‘Persuading the sons of confederate veterans to adopt a different perspective is a lost cause.’ People who want to write about the Black Confederate Soldier will never stop doing it because it is their perception of the sources and they believe it is true.

Madsen-Brooks further states that other groups could still be responsive to the help of historians to see the bigger picture. They could still be ‘saved’ from the digital realm she basically finds full of lies. Thus, historians should ‘increase digital literacy’ and provide alternative, ultimately more convincing, interpretations of primary sources.

I cannot help but wonder if that is really what the historian should do. Should a historian participate in this ‘yes/no-game’ and ‘fight’ for who is right or wrong? Will this not cause more harm than good to the credibility of the historian if he mingles himself in a black or white debate, whilst knowing as no other – and always proclaiming – that everything in history is grey and full of nuances? Thereby I also feel that the world wide web has become so wide that the concept of ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ has almost become irrelevant in that realm. There only seems to be the perception of many, many people who interact with each other.

So, what is next?

Instead of trying to fight a battle that cannot be won, the historian could look at this situation from a different point of view. The fact that blogs about the Black Confederate Soldier exist, means that some groups really think this information is true and that it needs to be shared. Historians hereby need to accept that the popular understanding of the past differs greatly from that of academic historians and that it often reflects a particular worldview. As such it may tell the historian as much about memory – how events are remembered – as it does about history.

For years, and especially since the rise of cultural history that wants to investigate the history of mentalities, historians have been on a quest for documents that describe how ‘the people’ think and feel. Is this online Black Confederate Soldier debate not the perfect source for this kind of historical research? What if the historians use these blogs to do what Pierre Nora liked to call the ‘history of the second degree’; to investigate the evolution of memories of people and how events are remembered? In that case the world wide web is the perfect lieu de mémoire, because it does exactly what this term suggests: it is a place where people show and write how and why they (want to) remember certain events or things.

Diane Staelens