While many people might recognize her unibrow and bright color palette, most are unaware that the work of Mexican artist and activist Frida Kahlo (1910-1954) is deeply shaped by her disability. Frida’s lifelong struggle with her health eventually resulted in the amputation of her lower right leg in 1953. The prosthetic leg she used during the last year of her life has become a symbol of her suffering and the source of her inspiration – and has been displayed in museums accordingly.

By Roos van der Tol

Kahlo’s right leg had been shorter and thinner since she was a child, because of polio that went without proper treatment. The decreased circulation to the limb caused her lifelong pain and health problems. In the last years of her life, Kahlo had her leg amputated due to gangrene after a failed bone graft surgery for spinal issues. She died not six months after the operation, possibly by her own hand.

After the operation, Kahlo started wearing a prosthetic foot, with a leather strap and a flesh-colored lower leg, that was similar to other prosthetic legs from that time. To hide her disability, Kahlo designed a lace-up red boot to fit her prosthetic leg.

Suffering as a source of inspiration

With the Chinese design painted on the side of the foot, Kahlo made the boot into art itself. As the New York Time writes: “Even the leg is a work of art”. This comment is indicative of the way the object is often perceived: as a contextualization of the art of Frida. The prosthetic is a visualization of her illness. Frida saw it that way too, as she writes herself right before her amputation:

“They want to hurt my pride by cutting a leg off […] (damned thing, it got what it wanted in the end). I told you I’ve counted myself as incomplete for a long time, but why the fuck does everybody else need to know about it too? Now my fragmentation will be obvious for everyone to see, for you to see…”

– Letter from Frida Kahlo to Diego Rivera, 1953. Digitalized at Letters of Note.

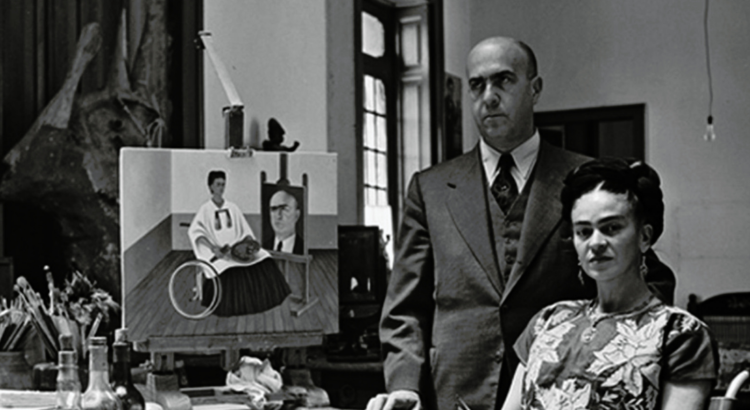

The emphasis is often put on the way her illness contributed to her art. She began painting at fifteen, when she was too bedridden after an operation to do anything else. Furthermore, her deteriorating health is a major theme is her work, ranging from her spinal operations to her miscarriages. Because she was bedridden, she figured as her own model, which is why her own face is heavily featured in her art and possibly become so famous today.

Prosthetics on display

After Frida Kahlo’s death in 1954, the prosthetic was sealed away in a vault along with her clothes and other personal belongings. This vault was left virtually untouched until 2004, when art historians from Casa Azul (Kahlo’s old house in Mexico City, now known as Museo Frida Kahlo) started taking inventory of the objects. The leg was first put on display in 2012 in Museo Frida Kahlo, between Kahlo’s other prosthetics, in the first room of the museum. Here, it provided an introduction to Kahlo’s life, while at the same time providing context for the art that the visitor will encounter next.

Since 2012, the prosthetic has travelled the world as part of several exhibits on Frida Kahlo’s clothes and image, such as the Frida Kahlo: Making Herself Up at the Victoria & Albert Museum, London and Frida Kahlo: Looks Can Be Deceiving at the Brooklyn Museum, New York. Since its discovery, the prosthetic has virtually always been on display with art and other clothes, to demonstrate Kahlo’s all-encompassing approach to her art and provide context as to how that art come to be.

The display of a prosthetic leg in a personal context, to illustrate an aspect of one’s life, is quite different from the usual prosthetic exhibition. Usually, prosthetics are displayed mostly in medical and technical displays, where the focus is on the medical, the injury. Additionally, when looking up other artificial limbs, the accompanying texts at institutions like the Science Museum Group and National Museum of American History are mainly focused on the military and medical uses. Since the research into prosthetics didn’t really take off until the First World War resulted in an increase in amputees, this makes sense in an historical perspective. However, objects heavily rely on their surroundings to derive meaning. When context and juxtaposition are concentrated around the medical aspect, there is a risk of the disease becoming isolated and abstract in the eyes of the beholder.

Paving the way: emerging of a new narrative surrounding disabilities

For a prosthetic to be displayed specifically to highlight a disability as part of someone’s life, such as Frida’s leg, shows that being disabled does not define an individual and can be a mere aspect of the person. By consistently placing the item between Frida’s art, the museums tell a refreshing story about how a disability affects an individual – and how it can be turned into something impactful, and beautiful.

Frida Kahlo’s honest and vulnerable portrayal of her health has sparked recognition and awe among the disabled community. Writer Emily Rapp Black, who lost her leg at age four, explains in her memoir Frida Kahlo and My Left Leg, how the work of the Mexican artist helped her develop a better relationship with her body. Research also indicates the impact of Frida Kahlo’s legacy on body politics. This new shift in narrative when displaying disability raises important questions about who has to gain from the exhibit, the portrayed or the public. Are displays of medical issues merely meant as a means of education for the public on the workings of science and the body, or should we start including the person who the disease or disability is a part of? And how do we combine the science with the social?

Want to know more? At the moment, the Cobra Museum has an exhibition on Frida Kahlo, with a special section on her health that displays pictures and some prosthetics. You can also visit Museo Frida Kahlo online, where Frida’s prosthetic leg is on display. For more information on the display of prosthetics throughout the past century, I highly recommend reading the article Prosthetic Limbs on Display: From maker to user by Sophie Goggins, Tacye Phillipson and Samuel Alberti.