Many people today might think that vegetarianism is a trendy lifestyle movement that has only emerged in the past two decades, but nothing could be further from the truth. The history of vegetarianism in the Netherlands stretches back over a hundred years. While plant-based eating is more popular than ever today, with climate change being a primary motivator for many vegetarians, the link between vegetarianism and environmental concerns is a relatively new development. So, what drove the first vegetarians in the Netherlands, and how has this motivation evolved over the past century?

The Dutch Vegetarian Society (“De Nederlandsche Vegetariërsbond”) was founded in 1894, at a time when the idea of a vegetarian diet was seen as almost unthinkable. In the late 19th century, a magazine based in Amsterdam mocked the notion of vegetarianism, arguing that vegetables provided no nourishment and that those who adopted this strange diet without any meat would have nothing substantial to eat. Nutritionists of the time reinforced this belief, stating that vegetables and fruit were not nutritious, while meat was considered the cornerstone of a healthy diet. Meat was not only believed to provide strength to individuals but also to the nation as a whole.

Given this context, why did those early vegetarians choose to stop eating meat, especially when it contradicted the widely accepted dietary norms? Surprisingly, it wasn’t the nutritional aspects of the diet that initially motivated them, but rather a broader lifestyle movement centered on health and in general being a good person in the Dutch society. Vegetarianism was often associated with a holistic approach to living, promoting a healthy, working individual who made conscious choices. The Dutch Vegetarian Society actively promoted vegetarianism through pamphlets and trough their own magazine, ‘de Vegetarische Bode’, but their messaging focused on solving other, sometimes quite random, societal issues rather than dietary concerns alone.

The first vegetarians

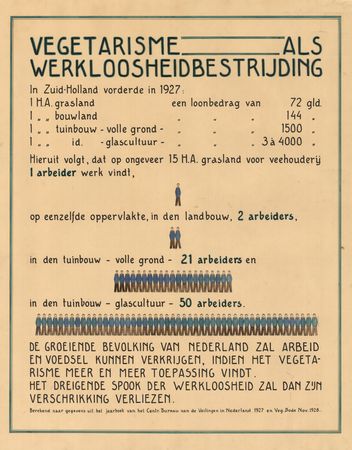

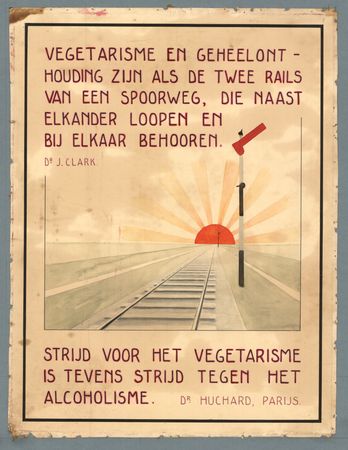

For instance, vegetarianism was seen as a solution for alcoholism, as illustrated by a pamphlet from the society. The image on the left pamphlet shows a railway leading to a bright and sunny future on the horizon, with the accompanying text: “Vegetarism and abstinence are like the two tracks of a railway, which lay right next to each other and belong together. The fight for vegetarianism is the same fight as against alcoholism.” This strong association between a meat-free diet and abstinence is quite interesting and promotes a certain lifestyle. Another benefit of a vegetarian diet, according to the Dutch vegetarian society, could be the reduction of unemployment. Several pamphlets argued that agriculture and horticulture, both labour-intensive industries, would provide more jobs than livestock farming. An example of such a pamphlet showed on the right, shows drawings of labourers, with a caption stating: “The growing population of the Netherlands will acquire food and labour, if a vegetarian diet will become more common.” Thus, before World War II, vegetarianism was mostly seen and promoted as a solution to societal problems and as part of a particular lifestyle.

Nature conservation and animal welfare

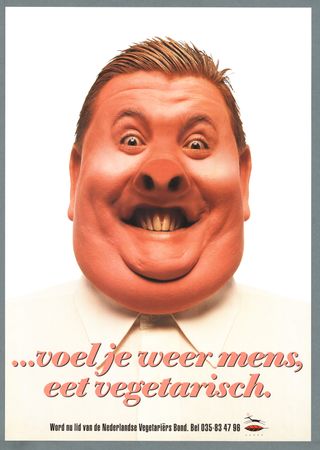

After World War II, however, this gradually changed, within the Vegetariërsbond and among vegetarians in general. There was an increasing emphasis initially on nature conservation and protecting the future of our landscape. This was mainly aimed at regular agricultural methods that were no longer sustainable: they caused climate change, desiccation and soil atomization. The vegetarians themselves were mainly advocating for the cultivation of plant-based alternatives to meat, such as beans etc., as these took up less space compared to livestock farming and were therefore less of a burden on farmland. This was also in response to the increasing industrialization of chicken and pig farming and the questions about the wellbeing of the farm animals. From the 1960s and onwards, animal welfare becomes the biggest motivation for vegetarians. De Nederlandsche Vegetariersbond promotes their diet focusing on animal welfare, like this pamphlet. It states “Feel human again, eat vegetarian”. Again, the focus was not yet on the emissions from livestock farming, but on animal welfare and nature conservation. During the 80s and 90s climate change became a topic more and more people were aware of and engaged with, but in a survey among the members of the Vegetariersbond in 1989 the reason ‘environment’ was not yet mentioned.

Climate crisis

This changed dramatically by 2013, when 63% of the society’s members cited environmental concerns or climate change as a reason to eat vegetarian. Today, plant-based diets are widely promoted through ads and campaigns urging consumers to make more conscious food choices, especially during initiatives like the Dutch National Week Without Meat. This shift is perhaps unsurprising in a world where the effects of the climate crisis are already being felt in the form of global warming, natural disasters, and biodiversity loss. For many, choosing what to eat seems like a simple yet powerful way to contribute to the fight against climate change.

Looking at the history of vegetarianism over the past century, it becomes clear that people have long viewed food choices as a way to address broader societal issues. While the motivations have evolved, from health and social improvement to animal welfare and environmental concerns, the relatively simple and personal way to make a small change, stays the same. The different motivations for a vegetarian diet through the last century shows us people can engage with complex, social challenges by making personal dietary choices.

Like to read more on this topic?

– Verdonk, D. Het dierloze gerecht. Een vegetarische geschiedenis van Nederland, (Amsterdam 2009).

Written by: Evita Minnaard