In “Ongekend bijzonder” (former) refugees give their life history. With a project on Indonesian veterans, “Verhalen van Groninger Indië-veteranen“, the Oorlogs- and verzetscentrum Groningen wanted be current to society’s issues. The Jewish Museum in Amsterdam brought a large selection of interviews of Jewish survivors of the Second World War from the USC Shoah Foundation Institute to the Dutch public, “Tweeduizend Getuigen Vertellen”. And realizing that there are fewer and fewer survivors of the “Watersnoodramp”, the Watersnoodmuseum started an oral history project collecting stories of victims, rescue workers and other directly involved: “1953, Het Verhaal”. And lastly an abundance of Facebook-sites are dedicated to the remembering of a specific city: ‘Herinner je …[insert specific city]”, for example “Herinner je je Amsterdam“. Concluding this opening with the observation: there are already an enormous amount of oral history projects, within the academic community as well as outside the community, by museums and the public.

The public remembering a site or event in recent history is of interest to a historian. Historians have had an interest in the public as topic for research for a while now. And historians have always relied on eyewitness accounts and personal stories as a source of information. Making contact with “ordinary” people and hearing them has been a more recent step in recording accounts of events. Now another step has to be made, arriving in this digital age historians cannot ignore the technological tools surrounding them. The use of digital tools is necessary in order to reach a new group of people. In short, they often use digital technology and so should we.

In 2006 Cohen and Rosenzweig created a guidebook to achieve an online platform with which the historian can effectively collect the stories of the public. Their step-by-step explanation on how to succeed in the process of collecting, preserving and presenting personal records contributed by the public is easily to follow. Which platforms are available, what are some of the possibilities in connecting to the public, which sources we can use, what are the basic necessities for an online oral history project? While urging critical thinking and remain confident of the use of the historical thinking skills Rosenzweig and Cohen give a positive view of an easily used medium.

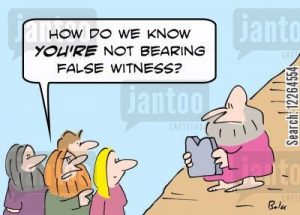

Remarkable are Rosenzweig and Cohen’s views on the purity of the collected materials. They have an incredible and unwavering trust in the public as far as their truthfulness. But they admit: “with great generosity sometimes comes undesired mischief” In their opinion the public will refrain from forgery and untruthfulness because of the nature of the mission of the collection: that it is historical. Who would want to mislead, embellish or improve their history? If we are to be critical about written sources delivered to us years and years ago, we must be at least maybe even more critical about the memories we are collecting.

When working with persons in real life or on digital history projects it would be necessary to divide their memories into the categories of history, their past and their historical and cultural identity: lieux de memoires. While in cultural studies the term of lieux de memoire is often used to explain the formation of cultural thinking and identity. This term was coined by Pierre Nora and defined as: a site of memory as an opposite of the term milieux de memoire, real environments of memory.

Collecting memories as if they are facts is a whole new world of history critique and writing, certainly when it is being pulled to a new technological era in which storing many eyewitness accounts has become more possible. I would propose that future historians work on methodologies like Rosenzweig and Cohen’s guidebook on how to use the Internet to collect and create source criticism for (modern) personal accounts. As Pierre Nora felt, there seems to be an acceleration of history. Lets hope we can create methods to catch up.

Eline Beumer

21/09/2016