‘A grey block of meat.’ This does not sound very appetising, but seeing balkenbrij, many would say this description is perfect. The dish looks unrecognisable in terms of ingredients, but those who do know it will describe it as ‘waste’ meat. Besides, it is often considered as nasty by those who know it; after all, it is rubbish. Yet the Albert Heijn’s freezer is full of frikandellen, waiting for someone to come along and take them for a party or football match. Why doesn’t this happen with balkenbrij? The problem with balkenbrij is, it is just so weird. After all, what exactly is in balkenbrij? Where exactly does it come from? And why is it a forgotten meat dish? Balkenbrij seems to be one big enigma.

Balkenbrij looks enigmatic, although there are not a lot of ingredients needed to make it. There are only three: leftover pork meat juices, buckwheat flour and rommelkruid (nutmeg, aniseed, liquorice root, ginger powder, pepper, mace, cinnamon and sandalwood). Pieces of leftover meat are also often added to the dish, but it actually consists mainly of the liquid from other meat dishes. This makes it a head-to-tail product, which means that everything from a slaughtered animal is fully used. Instead of going to the butcher, people used to slaughter their own animals. In the month of November, they had a nice, heavy pig, ready for slaughter. In the Brabants archive, where the only stories can be found in which balkenbrij appears, Jo van der Sloot writes that she remembers the balkenbrij well:

After a few days, the butcher came back to chop up the pig. My mother, aunts and neighbour did the dissecting of the pig later, they turned it into balkenbrij, zult and blood sausage, among other things. The good pieces were sold.

So, the meat dish was mainly made for sustainable considerations. Since meat was expensive, the whole pig was used for all meat dishes. Balkenbrij proved to be a creative recipe in this. Leftover liquid from a pig’s head? Balkenbrij. Moisture from cooked sausages? Balkenbrij. The making process was quite simple: put a mix of spices, moisture and flour (the brij) in a bag, hang it in the barn on a beam (balk) so that it can solidify into a firm substance. There’s the balkenbrij.

Elderly woman near slaughtered pig strung up on a ladder. Source: National Archives, Van de Poll photo collection.

However, the origin of balkenbrij is difficult to trace back in time. It is seen as something typically Brabants, although several provinces put their own spin on the dish. In Limburg, it is also known as barkoet or pannas, where they add blood to it; in Gelderland, they add currants and sultanas for a slightly sweeter dish. It remains a dish for southerners, though, as the North continues to eat it strangely. The word appears in 1871 in the book De Volkstaal in Noordholland, although its unfamiliarity also quickly becomes clear: ‘People make little use of balkenbrij here, because the method of preparation is less well known.’ Despite appearing in cookbooks for longer periods, there is nothing to point to the past of meat mash.

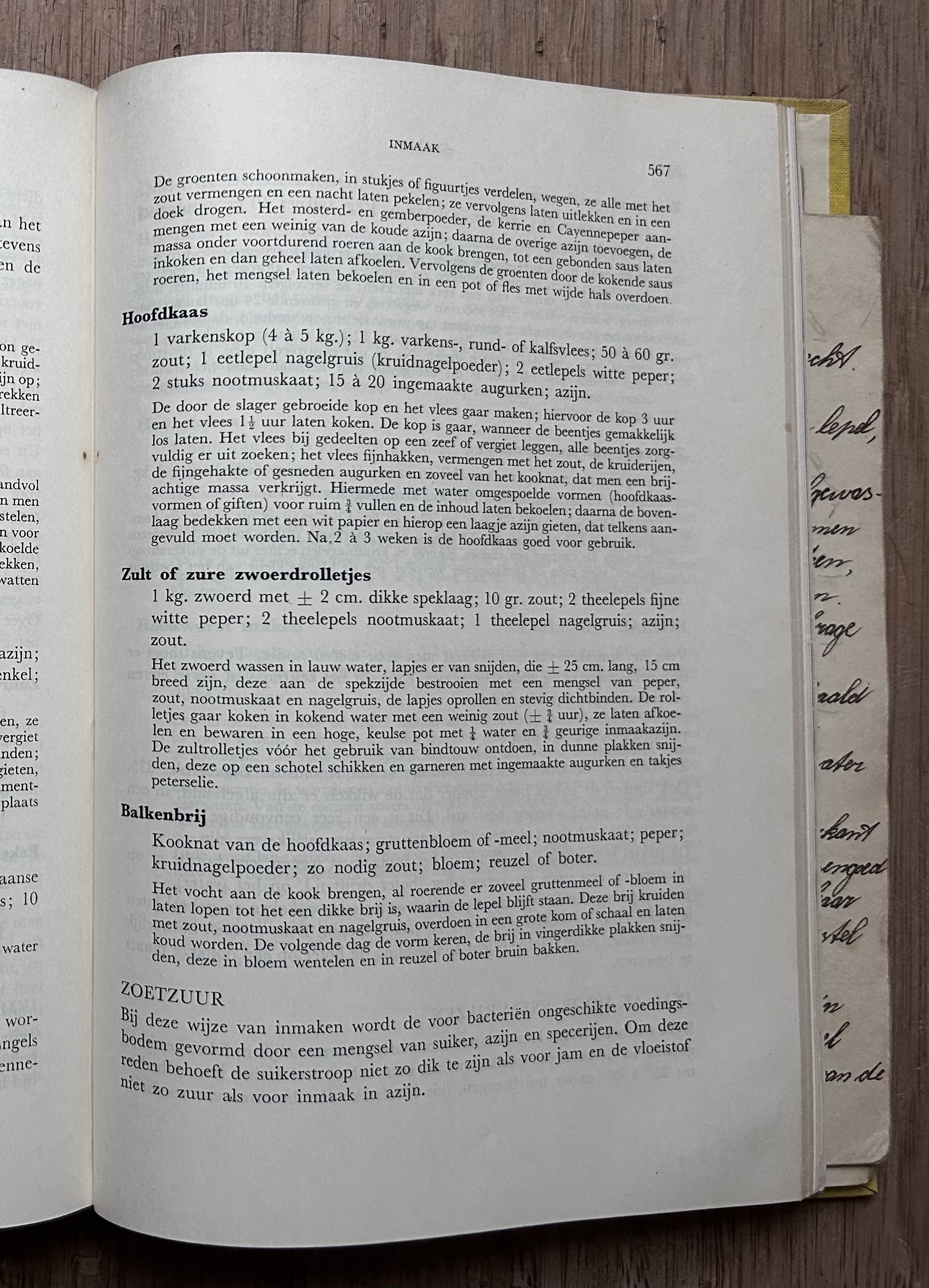

Balkenbrij among other ‘’waste‘’ dishes. In my parents’ cookbook, “I can cook”, from 1951.

Going beyond the borders of the Netherlands, we can look a little further into the history of balkenbrij. In Germany, there are also variations of the dish. For instance, knipp consists of offal and is considered ‘poor man’s food’. In addition, scrapple is a traditional dish in Pennsylvania, where it is eaten by the Pennsylvania Dutch. The origins of scrapple can again be traced back to the Netherlands and Germany. Because the food was easy and cheap to make, the dish was brought overseas under the guise of colonialism in the 18th and 19th centuries. By Americans, scrapple is traced to a Roman past. Because even in ancient Rome, meat was very expensive, so a slaughtered animal here was used in its entirety.

Pennsylvanian scrapple. Source: Pennsylvaia’s ‘other’ Meatloaf, Pennsylvania Center for the Book, by Krista Klinger.

Has balkenbrij really been forgotten now? Certainly not! On the contrary, it has become something very personal. As with Jo van der Sloot, the dish is etched in the memories of our southerners. The recipes are passed down within families and with them the taste. For instance, I myself ended up with balkenbrij because my mother occasionally makes it for me and she in turn inherited it from my grandparents. So balkenbrij is no longer made for sustainable reasons, but because it is eaten by people who want to remember the past and pass it on. It’s an intimate delicacy.

Balkenbrij at the Albert Heijn supermarket. Source: Albert Heijn.

Balkenbrij has stood the test of time. It has been around for centuries; it has changed from a poor man’s food to a delicacy, has traces of colonialism and is now fighting not to be forgotten. The internet is full of recipes involving balkenbrij again. A pasta, a risotto, even against the meatless era, balkenbrij is up for a fight; there is now a balkenbrij based mushrooms and tofu. It still remains a sustainable dish, but now in turn for the environment.

Written by Pieter van Iwaarden